Campus News

‘Petri Dish 2.0’: A new startup is bringing automation to biology’s most tedious tasks

Open Culture Science, a revolutionary new startup out of the UC Genomics Institute’s Braingeneers group, aims to accelerate the pace of biological research with their patented technology.

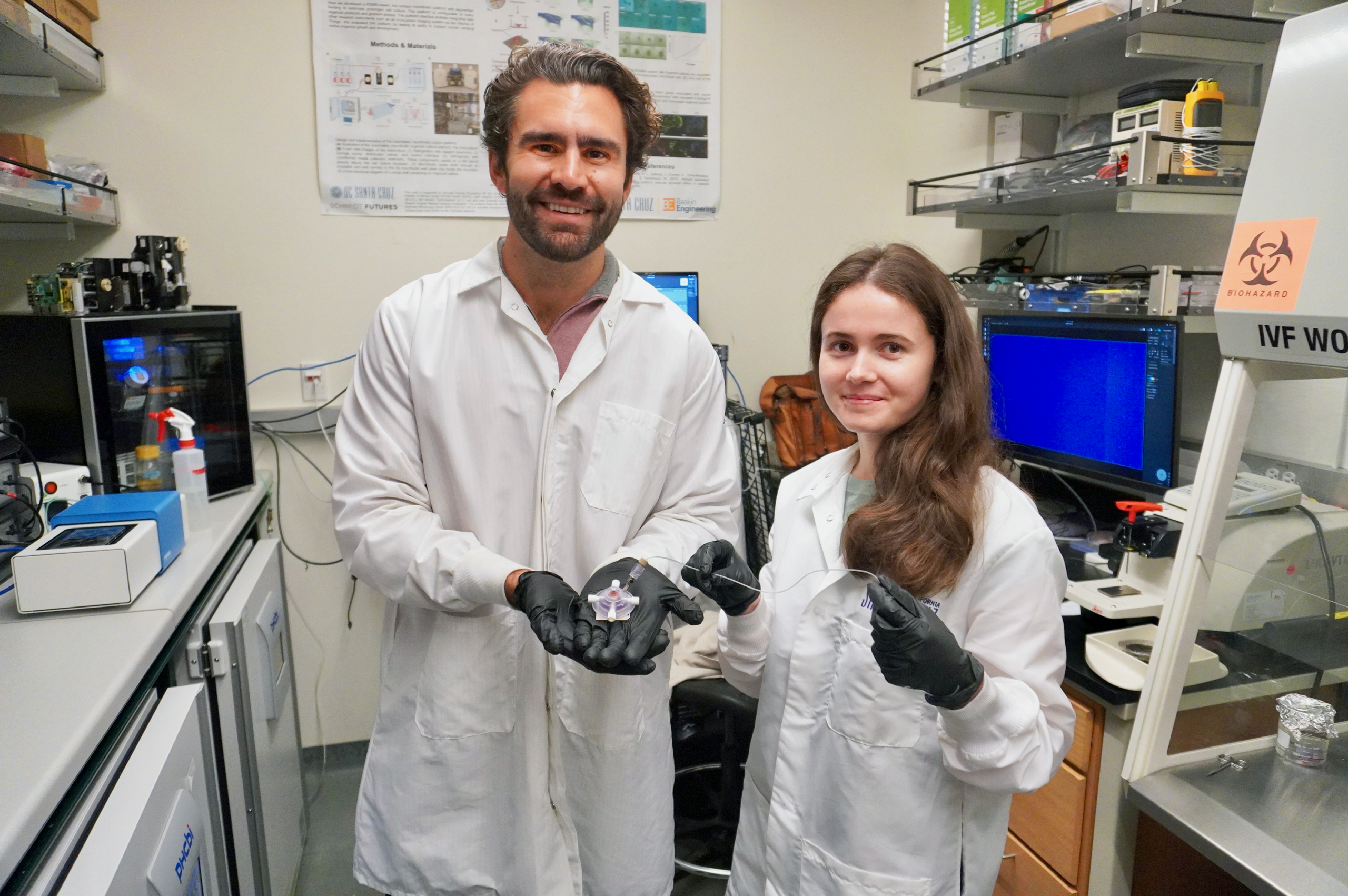

As members of the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, Spencer Seiler and Kateryna Voitiuk helped develop technology for automatically collecting data from delicate cell cultures. They are turning that tech into a company called Open Culture Science.

Key takeaways

- Spencer Seiler and Kateryna Voitiuk, Ph.D. graduates of the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, have founded Open Culture Science to automate the tedious, error-prone manual labor that slows down biology research.

- Using patented technology developed while they were part of the Braingeeners lab, the company is creating devices for keeping delicate cell cultures healthy.

- Open Culture Science is making the technology a part of open ecosystem in which labs can share protocols, accelerating scientific discovery worldwide.

Walk into almost any modern biology lab, and you’ll see researchers hunched over cell culture hoods, carefully pipetting nutrients into dishes and monitoring incubators. It’s essential work, but it’s often the rate-limiting step in research that otherwise moves at digital speeds.

The problem, according to Spencer Seiler, a graduate alum of the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, is that in terms of the technology for conducting basic biology, “we haven’t advanced much past the pipette.” This has created a bottleneck in an industry otherwise defined by rapid progress and automation.

Seiler and UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute alum Kateryna Voitiuk aim to eliminate this bottleneck with a revolutionary new startup, Open Culture Science. The company is built around the deceptively simple idea that many of the most tedious tasks in biology can and should be automated. Their product, which they have described as a “Petri Dish 2.0,” aims to transform cell culture from a fragile art form that is prone to error into a programmable system that researchers can run, share, and replicate anywhere in the world.

“Our goal is to make biologists as productive as software engineers,” Voitiuk said.

Solving an initial challenge for brain organoids

The roots of Open Culture Science stretch back to the early days of a research group known as the Braingeneers. Over the past several years, this interdisciplinary initiative led by the Genomics Institute uncovered discoveries about neural plasticity, the origins of thought, the genes associated with neurological disorders, and a potential new treatment for epilepsy.

Central to these discoveries are brain organoids—miniature, three-dimensional structures grown from stem cells that mimic aspects of the developing human brain. In the early days of research using these models, it was a constant struggle just to keep these unique cell cultures alive.

In 2016, Genomics Institute Research Scientist Sofie Salama (now Professor of Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology), sent out a mass email asking if anyone could help 3D-print her a customized bioreactor—a special vessel used to support the growth of cells and tissues. The brain organoids Salama was cultivating were not thriving in those that were commercially available. Voitiuk, who has had something of an obsession with 3D printing since high school, was fascinated.

“When I got that email, I was thinking, ‘Oh my God, I need to help because this is the coolest thing I’ve ever read,’” Voitiuk recalled.

Shortly after, Voitiuk attended the first official meeting of the Braingeneers, along with Salama, UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute Scientific Director and Distinguished Professor of Biomolecular Engineering David Haussler, Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Biomolecular Engineering Mircea Teodorescu, and several collaborators from UC San Francisco. The group discussed the incredible potential of organoids for understanding the brain in new ways, but since organoid research was relatively new at the time, there was no real guidebook for how to best cultivate these complex cell cultures. They had to solve numerous practical problems to consistently provide the organoids with the proper nutrients they needed to thrive—frustrating challenges that would eventually inspire Open Culture Science.

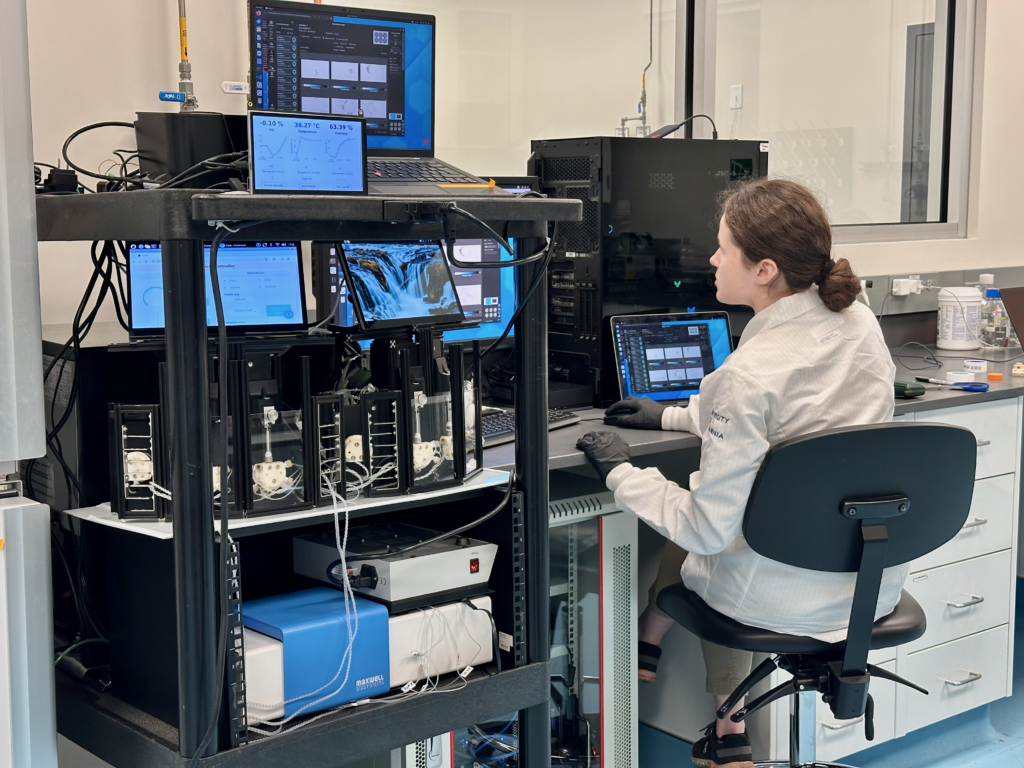

“The Braingeneers team is unusual because we bring bioengineers and biologists into the same loop,” Teodorescu said. “Over the past several years, we’ve built automated systems to keep organoids healthy long-term while also measuring and perturbing their electrical activity. Most labs don’t have the engineering bandwidth to build that infrastructure from scratch, so it’s exciting to see Spencer and Kateryna turning it into a product that can make advanced cell culture more reproducible and widely accessible.”

A powerhouse partnership

Seiler joined the Braingeneers in 2019, just as Voitiuk was transitioning from an undergraduate research assistant to a graduate researcher focused on recording neural activity from organoids. Seiler had been an early member of three Bay Area startups, and he brought a unique perspective to the work of the Braingeneers.

After holding roles at Berkeley Lights and Ultima Genomics, both of which were valued at over a billion dollars at their peak, Seiler had decided to pursue a graduate degree at UC Santa Cruz so he could be on the ground where the latest innovations were being developed. When he saw the problems the Braingeneers were solving to research living cells, he realized that labs everywhere could benefit from automated technology.

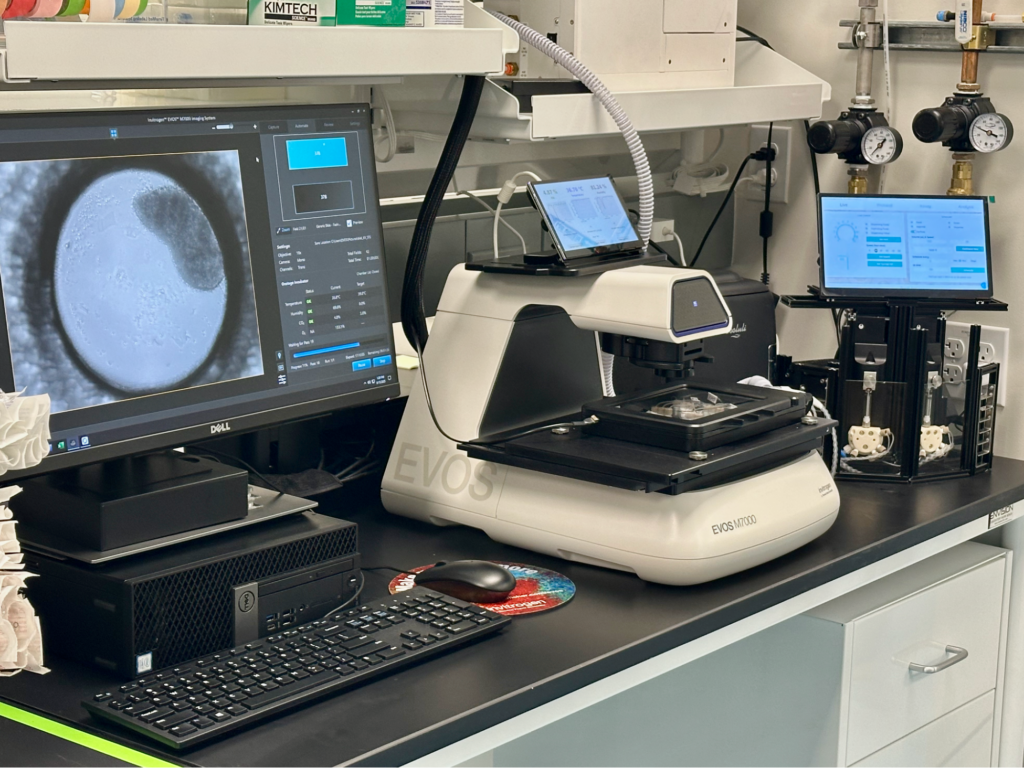

Soon, Seiler and Voitiuk began working together on a pair of papers that laid the groundwork for their current technology. They first introduced an automated cell culture “Autoculture” system that used tiny channels and robotic pumps to supply nutrients for organoids, and they found that the robotic system made the cells healthier than when researchers supplied nutrients by hand. The second laid out an Internet of Things system in the lab for connecting devices, such as the Autoculture platform that supplies nutrients to organoids and the device that records neural signals, so that these tools can be controlled and coordinated remotely.

“After publishing our papers, we realized we were holding technology that is solving problems for us, and also looks to be solving problems for a lot of other labs,” Voitiuk said.

They applied to the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program and conducted customer discovery across bio hubs in San Diego, the Bay Area, Seattle, and Chicago. Almost all of the researchers they talked to had the same refrain: repetitive and time-consuming tasks were limiting what they were able to accomplish. In July 2024, as they were both preparing to finish their degrees, they officially founded Open Culture Science.

A revolutionary technology built for simplicity

Now, Open Culture Science is expanding on the work the founders started with the Braingeneers to create a fleet of automated devices that they believe will have a huge impact on both academic research and the pharmaceutical/biotech industries that make extensive use of cell cultures.

While they’ve cut their teeth on cerebral organoids, which are considered one of the most challenging models, the technology’s potential applications are vast.

“You could put bacteria there, fungi, phages, viruses—we don’t yet know what the limits are,” Voitiuk said.

They aim to make the technology so easy to use that a high school student could perform simple experiments.

“You’ll open it up a little bit like the iPhone experience,” Seiler said. “The user interface will guide you through how to operate it. You can talk to it, communicate with this piece of technology. We want that on day one of purchase, this manages the tasks that you hated.”

Building an ecosystem of collaboration

Beyond the equipment itself, Open Culture Science’s most important innovation is the collaborative ecosystem they’re building. The company’s name comes from its strategy of creating a user community that will contribute open protocols that others can use on their platform. Under this model, users become application specialists.

“Let’s say a top-tier lab has this beautiful way of assembling a certain aspect of the brain, maybe the hippocampus, and they’re really the best at that,” Seiler explained. “If they walk through the procedure and get it to be a software protocol on our device, now that hits the cloud, and anybody who has our device can click that and produce that at their lab. This is where we get a snowball effect. Every user that’s producing data is building the value of this subscription.”

Their vision is a shared ecosystem in which biological methods spread rapidly and reproducibly, accelerating not just individual projects, but scientific progress as a whole.

This model for facilitating open scientific collaboration was inspired by the data-sharing culture of the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, which has been credited with normalizing the idea that genomic data should be freely accessible and creating the infrastructure for making this data a shared public resource through their flagship tool, the UCSC Genome Browser. When the Browser launched in 2000, open collaboration over shared data was still a radical concept. It has since fueled much of the rapid progress in genomics over the last 25 years.

“We’ve been inspired by the Genomics Institute, the Human Genome Project, and Genome Browser to create a tool that will enable the scientific community to create amazing science and share it with one another,” Voitiuk said. “If we can create a vessel that allows people to share their research in a programmatic and reproducible way that will level up science—that is the goal.”

The road ahead

Open Culture Science has recently completed a Pre-Seed funding round to produce pilot commercial products. The company holds an exclusive IP license from UC Tech Transfer to commercialize technology derived from UC Santa Cruz’s Genomics Institute. Open Culture Science has opened its first office in the Wrigley Building on the Westside of Santa Cruz, intended for manufacturing and research development.

The timing of the company’s launch may be fortunate: the 2023 FDA Modernization Act opened the door for organoid models to replace some animal testing in pharmaceutical drug discovery. As more labs adopt organoid research, systems like the one Open Culture Science is building could become essential infrastructure.

“Open Culture Science is tackling one of the biggest bottlenecks in experimental biology: the gap between what we can design as protocols and what we can reliably execute by hand,” Teodorescu said. “If complex cell culture becomes programmable and reproducible, it doesn’t just save time, it makes experiments easier to share, compare, and scale across labs.”

Both founders continue to be advised by members of the Braingeneers, and credit the culture at UC Santa Cruz’s Genomics Institute for enabling their journey from graduate students to entrepreneurs.

“I can proudly say it was a haven for research,” Seiler said. “The environment, the culture that was led by the Braingeneers—Sofie Salama, Mircea Teodorescu, David Haussler—was a place that thrived for research. We were permitted to pursue whatever good idea that we had. This operated as our own incubator.”

The next stage of Open Culture Science will be to finish the first product offering and raise a venture-backed Seed round this year to service more active users. The company is currently looking for like-minded engineers, leaders, and investors to join them in their mission. They’re also seeking pilot partners—academic labs, core facilities, biotech teams, and biopharma groups—to help test and shape the first generation of the device. To learn more about Open Culture Science or to inquire about partnership opportunities, visit openculturescience.com.