Campus News

New long-term NIH grant supports breast cancer research

Cancers are easier to treat if caught early on in their development. Once the cancer cells metastasize and spread around the body, the disease becomes more difficult to target. Shaheen Sikandar, an assistant professor of MCD Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, was recently awarded up to seven years of funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institute of Health (NIH), to study the process of metastasis in breast cancer.

Cancers are easier to treat if caught early on in their development. Once the cancer cells metastasize and spread around the body, the disease becomes more difficult to target. Shaheen Sikandar, an assistant professor of Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, was recently awarded up to seven years of funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institute of Health (NIH), to study the process of metastasis in breast cancer.

The R37 MERIT Award from the NCI supplies $344,000 per year for a guaranteed five years. In the fourth year of her grant, Sikandar can apply for two additional years, which would bring the total award amount to $2.4 million. The funding will support Sikandar’s lab in researching why certain breast cancer cells metastasize.

“And if we can understand the mechanisms as to what’s going on within those cells, we’ll have a better way to treat metastatic disease,” said Sikandar.

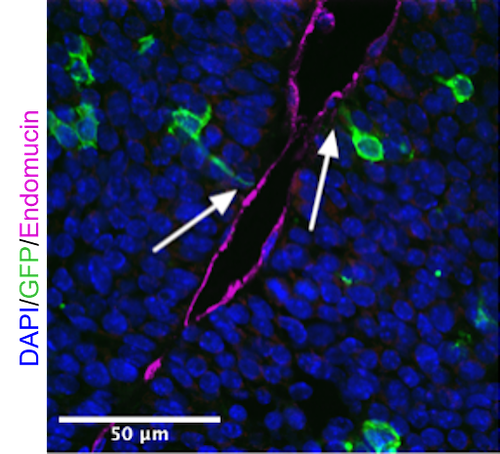

Before joining UC Santa Cruz three years ago, Sikandar identified a small population of cells within breast cancer tumors that are more likely to metastasize than other cancer cells from the same tumor. These cells, known as LMO2+ cells, only make up one to two percent of tumor cells. But their impact is major. Cells that express the LMO2 gene exhibit more plasticity—the ability to change characteristics—and are more likely to metastasize.

Sikandar’s lab has already made some progress in understanding the cells. Isobel Fetter, a UC Santa Cruz PhD Candidate in Sikandar’s lab, found that the LMO2 gene regulates which DNA repair pathway a cancer cell chooses. This could have implications in cancer therapy, Sikandar says. But several questions remain.

“Why do only one to two percent of cells express LMO2,” asked Sikandar. “And even though it’s such a minority population, it has such a big impact on the metastasis. So is there a way that we can target this minority population of cells?”

The new grant will ensure long-term, stable funding for continuing the work. The lab will use a combination of patient-derived xenografts, mouse models and cell lines to better understand the LMO2+ cells.

“I’m elated,” said Sikandar, adding that she would’ve been happy with a standard, five-year R01 grant. “But the fact that it was an R37 is even better because I have an opportunity for two more years,” she said. “So I’m very excited about it.”