Campus News

Kathleen Finlay brings UCSC education to the forefront in her fight for food sustainability and social justice

UC Santa Cruz alumna Kathleen Finlay is the president of the Glynwood Center for Regional Food and Farming in the Hudson Valley and founder of Pleiades.

Much like other UC Santa Cruz alumni and current students, Kathleen Finlay (Crown ’95, biology) was invested in the natural surroundings of the campus, and how they intersected with the human experience.

Now, Finlay—president of the Glynwood Center for Regional Food and Farming in the Hudson Valley and founder of Pleiades—has advanced her undergraduate experiences along the Pacific Coast into action.

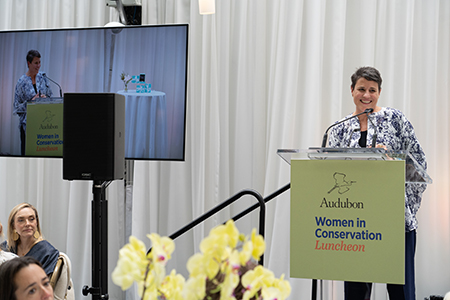

On May 5, Finlay was one of three female leaders honored at the 20th annual Women in Conservation luncheon, hosted by the National Audubon Society at Bryant Park Grill in Manhattan. According to the Audubon Society’s event press release, the prestigious award recognizes visionary women whose “dedication, talent and energy have advanced positive environmental change locally and on a global scale.”

As National Audubon CEO Elizabeth Gray shared with the audience, Finlay and her counterparts’ leadership in both sustainable or regenerative farming and toward creating a sustainable future “embodies the true spirit of the award.”

For Finlay, that desire for a more sustainable future began when she first came to UCSC’s campus. She had originally wanted to study physics or “natural philosophy,” but her interests soon turned to biology because of the local environment.

“I was just being immersed in the campus amongst the redwoods and along the Pacific Ocean, which was formative in deepening my passion around thinking about the world we live in,” she said.

The Sacramento native began taking biology, marine biology and writing courses, and took lessons from the university’s Science Communication Master’s program, which helped compel her to “communicate what I felt were really important ideas about how we can live in the world more harmoniously.”

“The idea of writing and thinking of environmental issues was at the core of my inquiry at UC Santa Cruz,” she said.

Finlay had another environment to also expand on her understanding of the natural world: her mother’s native country of Bermuda. Upon Finlay’s move to Santa Cruz, her mother returned to Bermuda; upon graduation, Finlay moved to the country as well.

In Bermuda, Finlay volunteered for a number of nonprofits and worked on environmental issues, all while planning to attend graduate school. She soon thereafter moved from the island nation to Boston to attend Boston University, where she focused on science journalism.

“When I got my graduate degree, I also realized I didn’t want to be a science journalist, because I was too opinionated about what I thought could happen,” she said of the time, often going between Bermuda and Boston. “I wanted to be on the nonobjective side of a movement.”

On returning to Bermuda, Finlay then worked for a U.S. Oceanographic Institution based in Bermuda in their communications department. From there, she joined Harvard Medical School’s Center for Health and Global Environment, eventually becoming a managing director during her 11 year tenure there.

In that position, she studied and wrote about the relationship between the ocean and human health, with seafood being one of the primary and important connections.That led Finlay to develop an interest and attraction to using food in ways that “help people understand how much a part of the natural world we are.”

“Food is a really tangible way that all of us interact with ecosystems—it is a very fine vehicle for having conversations about our interdependence and connection to the natural world,” she said.

Finlay took those seedlings to help plant the way to creating a food-centered program at Harvard Medical School, where she remained until 2012. Eventually, Finlay yearned to do something less academic by implementing tangible actions that could lead to better health outcomes for people and the planet.

That’s what inspired her to join the Glynwood Center for Regional Food and Farming, a nonprofit serving food and farming changemakers from its home base in New York’s Hudson Valley. The organization works to advance local food production, educate a national audience, and promote regenerative agriculture, all in service of the natural environment, local economies, and human health.

The center has a demonstration farm which they use for education programming, a residential apprenticeship program, and a market development team for specific food sectors across the state.

Since Finlay joined the organization 11 years ago, the center has tripled the scale of its work, while also evolving to address food justice, food sovereignty and food equity.

“You know, 11 years ago, the kind of food that we think is a basic human right—healthy, beautifully produced, culturally appropriate—was celebrated as something that was for the elite or well-resourced folks,” she said. “We’re really trying to shift that paradigm, to acknowledge that we all deserve dignified food.”

Looking back to her time on the West Coast among the redwoods, Finlay believes that there are aspects of her UC Santa Cruz education that directly relate to her current work.

“Just the privilege of walking amongst those trees has stayed with me—it was a culture that truly acknowledged the natural beauty around us,” she said. “Those experiences were incredibly formative.”

Further, she said, her lifelong friends and mentorships made the experience of being a Slug all the more imperative to her current work.

“Those relationships I started at UCSC that I treasure, that are really loving, respectful and caring, I have to think that the overall culture of the university gets some credit.”