Campus News

NASA releases Webb telescope’s first exoplanet image

UCSC astronomers led the analysis of the first exoplanet images captured by the James Webb Space Telescope.

For the first time, astronomers have used the James Webb Space Telescope to take a direct image of an exoplanet (a planet outside our solar system). The planet is a gas giant, meaning it has no rocky surface and could not be habitable.

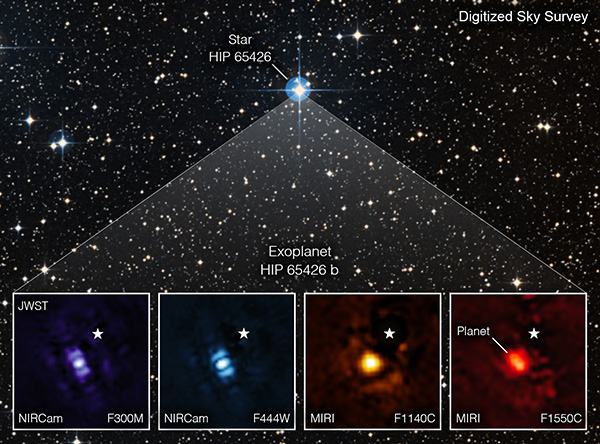

The image, as seen through four different light filters, shows how Webb’s powerful infrared gaze can easily capture worlds beyond our solar system, pointing the way to future observations that will reveal more information than ever before about exoplanets.

Aarynn Carter, a postdoctoral scholar working with Astronomy Professor Andrew Skemer at UC Santa Cruz, led the analysis of the image data.

“I’ve spent the last five years preparing for these observations, and seeing them not only succeed, but exceed expectations is exhilarating,” Carter said. “I think what’s most exciting is that we’ve only just begun. There are many more images of exoplanets to come that will shape our overall understanding of their physics, chemistry, and formation.”

Sasha Hinkley, associate professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, led these observations with a large international collaboration, including Skemer, who is a co-principal investigator of the program.

“This is a transformative moment, not only for Webb but also for astronomy generally,” Hinkley said.

The exoplanet in Webb’s image, called HIP65426 b, is about six to eight times the mass of Jupiter. It is young as planets go—about 15 to 20 million years old, compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old Earth.

Astronomers discovered the planet in 2017 using the SPHERE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, and took images of it using short infrared wavelengths of light. The Webb image, taken in mid-infrared light, reveals new details that ground-based telescopes would not be able to detect because of the intrinsic infrared glow of Earth’s atmosphere.

Researchers have been analyzing the data from these observations and are preparing a paper they will submit to journals for peer review. But Webb’s first capture of an exoplanet already hints at future possibilities for studying distant worlds.

Since HIP 65426 b is about 100 times farther from its host star than Earth is from the sun, it is sufficiently distant from the star that Webb can easily separate the planet from the star in the image.

Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) are both equipped with coronagraphs, which are sets of tiny masks that block out starlight, enabling Webb to take direct images of certain exoplanets like this one.

“It was really impressive how well the Webb coronagraphs worked to suppress the light of the host star,” Hinkley said.

Taking direct images of exoplanets is challenging because stars are so much brighter than planets. The HIP 65426 b planet is more than 10,000 times fainter than its host star in the near-infrared, and a few thousand times fainter in the mid-infrared. In each filter image, the planet appears as a slightly differently shaped blob of light. That is because of the particulars of Webb’s optical system and how it translates light through the different optics.

“Obtaining this image felt like digging for space treasure,” Carter said. “At first all I could see was light from the star, but with careful image processing I was able to remove that light and uncover the planet.”

While this is not the first direct image of an exoplanet taken from space—the Hubble Space Telescope has captured direct exoplanet images previously—HIP 65426 b points the way forward for Webb’s exoplanet exploration.

In addition to Carter and Skemer, other UC Santa Cruz astronomers involved in this work include Brittany Miles, Jonathan Fortney, Bruce Macintosh, Sagnick Mukherjee, and Callie Hood, as well as Xi Xhang in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

The James Webb Space Telescope is an international mission led by NASA in collaboration with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).