Campus News

New global forecasts of marine heatwaves foretell ecological and economic impacts

The forecasts could help fishing fleets, ocean managers, and coastal communities anticipate the effects of marine heatwaves.

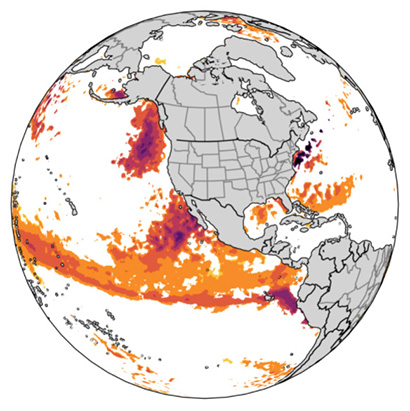

Periods of unusually warm ocean temperatures known as marine heatwaves can dramatically affect ocean ecosystems. Researchers have now developed global forecasts that can provide up to a year of advance warning of marine heatwaves.

The forecasts could help fishing fleets, ocean managers, and coastal communities anticipate the effects of these events. Described in a paper published April 20 in Nature, the forecasts were developed by a team of scientists affiliated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the UC Santa Cruz Institute of Marine Sciences.

“Forecasts of extreme events in the marine world are essential to climate adaptation and ensuring our coastal communities are resilient,” said coauthor Stephanie Brodie, a project scientist at the Institute of Marine Sciences who is also affiliated with NOAA. “We can accurately predict marine heatwaves, in some cases up to a year in advance, which is really useful for people faced with making decisions in the near term.”

One such heatwave, known as “the Blob,” emerged in 2014 in the northeast Pacific Ocean and persisted through 2016. It led to shifting fish stocks, harmful algal blooms, entanglements of endangered humpback whales, and thousands of starving sea lion pups washing up on beaches.

“We have seen marine heatwaves cause sudden and pronounced changes in ocean ecosystems around the world, and forecasts can help us anticipate what may be coming,” said lead author Michael Jacox, a research scientist at NOAA who is also affiliated with UCSC’s Institute of Marine Sciences.

Marine heatwave forecasts will be available online through NOAA’s Physical Sciences Laboratory. The researchers called the forecasts a “key advance toward improved climate adaptation and resilience for marine-dependent communities around the globe.”

The forecasts leverage global climate models to predict the likely emergence of new marine heatwaves. “This is a really exciting way to use existing modeling tools in a much-needed new application,” Jacox said.

Reducing Impacts

Impacts of marine heatwaves have been documented in ecosystems around the world, particularly in the past decade. These include:

- Fish and shellfish declines that caused global fishery losses of hundreds of millions of dollars

- Shifting distributions of marine species that increased human-wildlife conflict and disputes about fishing rights

- Extremely warm waters that have caused bleaching and mass mortalities of corals

On the U.S. West Coast, marine heatwaves gained notoriety following the Blob, which rattled the California Current Ecosystem starting in 2014. That marine heatwave led to an ecological cascade in which whales’ prey was concentrated unusually close to shore, and a severe bloom of toxic algae along the coast delayed opening of the valuable Dungeness crab fishery. Humpback whales moved closer to shore to feed in some of the same waters targeted by the crab fishery. As fishermen tried to make up for lost time after the delay by deploying additional crab traps, whales became entangled in record numbers in the lines attached to crab traps.

Recent research has also connected marine heatwaves along the West Coast to a northward shift in California market squid, which have long supported one of California’s largest commercial fisheries.

NOAA Fisheries scientists have since developed a Marine Heatwave Tracker that monitors the North Pacific Ocean for signs of marine heatwaves. The forecasts go a step further to anticipate where marine heatwaves are likely to emerge in coming months, and how long they are expected to persist.

“Extreme events in concert with increasing global temperatures can serve as a catalyst for ecosystem change and reorganization,” said coauthor Elliott Hazen, a research ecologist at NOAA and adjunct professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UCSC. “While marine heatwaves can have some unanticipated effects, knowing what’s coming allows for a more precautionary approach to lessen the impact on both fisheries and protected species. Understanding the ocean is the first step towards forecasting ecological changes and incorporating that foresight into decision-making.”

El Niño

The forecasts are most accurate during periods influenced by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a well-known climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean. In fact, El Niño (the warm phase of the oscillation) could be considered the “world’s most prominent marine heatwave,” Jacox said. It demonstrates that the heatwaves themselves are not new.

The forecasts cannot predict marine heatwaves as far in advance in regions such as the Mediterranean Sea, or off the U.S. East Coast. The atmosphere and ocean fluctuate more rapidly in these areas. The forecasts provide the greatest foresight in areas with known ocean-climate patterns such as the Indo-Pacific region north of Australia, the California Current System, and the northern Brazil Current.

“The global focus of this study highlighted for me that there are regions out there being affected by marine heatwaves that we haven’t seen in the scientific literature,” Brodie said. “Marine heatwaves do occur globally, and we want to enable everyone to look at forecasts in their regions.”

The scientists noted that managers of fisheries and other marine life must weigh their reaction to predicted marine heatwaves based on the potential consequences. For example, they would need to weigh the economic costs of limiting fisheries ahead of a marine heatwave against the risk of inadvertently entangling endangered whales or sea turtles.

“We’re talking about the difference between making informed choices and reacting to changes as they impact ecosystems,” Hazen said. “That is always going to be a balance, but now it is a much more informed one.”