Campus News

‘From the Margins: Dante 701 Years Later’ to provide critical perspectives on author’s work

Funded through the Siegfried B. and Elisabeth Mignon Puknat Literary Studies Endowment and presented by The Humanities Institute, the series will include events taking place throughout 2022 to engage with Dante’s work through a much different lens than the usual discussions of his life and work.

Last year marked the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, the Italian poet and author of The Divine Comedy, one of the most influential literary works in human history. In celebration of that milestone, events were held around the world, including some overseen by Santa Cruz’s own Dante Alighieri Society. But while UC Santa Cruz literature professor and Dante expert Filippo Gianferrari considered following suit, he chose to hold off on observing the poet’s passing in 1321 until this year.

“I was a bit annoyed that there were so many things going on,” said Gianferrari with a laugh. “It just seemed a bit hysterical. So I thought, ‘Yes, let’s do something but let’s take a different approach. Not a way to commemorate the poet and his achievements but more a way to engage with him critically.”

With that in mind, Gianferrari is helping organize a new series called From the Margins: Dante 701 Years Later. Funded through the Siegfried B. and Elisabeth Mignon Puknat Literary Studies Endowment and presented by The Humanities Institute, the series will include events taking place throughout 2022 to engage with Dante’s work through a much different lens than the usual discussions of his life and work. While he is rightfully placed on a pedestal for his startling visions of the afterlife in the Comedy and his lyric poetry, which are still resonating within popular culture some seven centuries after they were written, Dante was, in Gianferrari’s view, “a marginal intellectual during his lifetime”

“He was really working from the margins,” he said. “He was a layperson. He was not necessarily academically trained. He was exiled from his city. He decided to write in the vernacular, which was not the language of the learned establishment.”

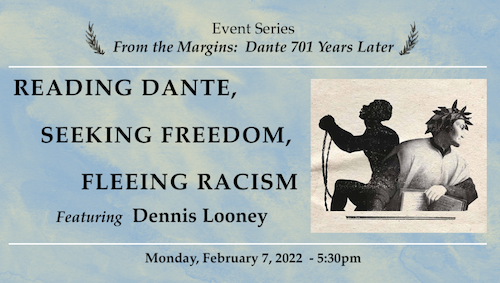

The first From The Margins event, an online webinar at 5:30pm today (Feb. 7), is a perfect encapsulation of how far-reaching Dante’s influence continues to be. Reading Dante, Seeking Freedom, Fleeing Racism will be a discussion of how Black writers have been using Comedy as inspiration for their own writing and re-interpreting its narrative as commentary on segregation and integration. The event will be recorded and available to view on the UC Santa Cruz Arts and Lectures YouTube channel.

Helping lead the discussion is Dennis Looney, a professor of Italian and Classics at University of Pittsburgh, and the author of Freedom Readers: The African American Reception of Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy, published by University of Notre Dame Press in 2011.

“There’s been a lot written about the reception of Dante by the poets that worked around Harvard like Longfellow,” said Gianferri, “but what Looney does with his book is tell a different story. The African American reception of Dante shows a very different view of Comedy. They saw the poem as one that does not serve established, imperialistic power but one that goes against it.”

The series continues on Feb 22 with a virtual event, co-sponsored by The Humanities Institute and the Center for Middle East and North Africa, called Dante’s Mediterranean Awakening. The conversation, moderated by UC Santa Cruz literature professor Sharon Kinoshita and featuring Karla Mallette, professor of Italian and Mediterranean Studies at the University of Michigan, will focus on the years Dante spent in exile from his home in Florence. As he traveled throughout Italy, the poet learned about the new technologies and new intellectual practices brought to the country from elsewhere including the teachings of Islam and new perspectives on the afterlife.

In the fall, says Gianferri, UC Santa Cruz will host another talk about Primo Levi, the Italian scientist and author best known for If This Is A Man, his account of his arrest as part of the anti-fascist movement in Italy and subsequent incarceration at the Auschwitz concentration camp. During his imprisonment, Levi began to recall the Dante poems he learned in school. In particular, he recited Canto XXVI from Comedy, Dante’s interpretation of the story of Ulysses’ last voyage, and attempted to translate into French for one of his fellow prisoners.

If all of these events only prove one thing, it’s that Dante has achieved something all-too-rare in the world of literature: longevity. There aren’t many writers whose work is still being discussed and analyzed and recontextualized for modern readers and scholars some seven centuries after it was printed for the first time.

It’s an incredible accomplishment for someone who, Gianferrari emphasizes, spent his most important years living and writing outside the boundaries of his home country’s cultural center.

“He wasn’t a professor giving voice to the official academic view of his time,” said Gianferrari. “He was not a priest. He was not a theologian. He was almost like a songwriter nowadays. His poems raise issues that are really difficult to address and because of that, they are still very much alive today.”