Campus News

New book chronicles more than 50 years of elephant seal research at Año Nuevo Reserve

Professor Emeritus Burney Le Boeuf summarizes the findings of the UC Santa Cruz elephant seal research program, one of the longest running studies of any animal

Burney Le Boeuf saw his first elephant seal shortly after his arrival at UC Santa Cruz in 1967, when a colleague took him out to Año Nuevo Island.

“It was the beginning of the breeding season, and I was seduced by their behavior and the research possibilities,” he recalled. “I was writing a grant proposal in my head as we drove back to Santa Cruz after that first visit.”

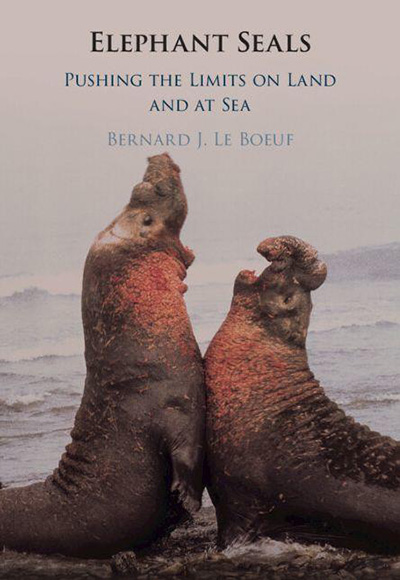

Thus began the UC Santa Cruz elephant seal research program, a remarkable long-term study of an extraordinary animal. Le Boeuf, now a professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at UCSC, summarizes the findings of more than 50 years of elephant seal research in a new book, Elephant Seals: Pushing the Limits on Land and at Sea (Cambridge University Press, November 2021).

“These animals are fascinating because they stretch the boundaries of what can be done both on land and at sea, pushing the behavioral and physiological limits of adaptation,” he said.

They are the largest seals, with males weighing over two tons. Elephant seals dive deeper and longer than any other seals or sea lions, and while at sea they spend 90 percent of their time submerged (more than most whales). The differences between the sexes are extreme, with males three to 10 times larger than females, and their polygynous mating system is also extreme. A dominant “alpha” male may mate with hundreds of females, while most males seldom or never mate, which leads to fierce battles for dominance among the males. Alpha males stop eating and barely sleep for more than 100 days during the breeding season, and females fast while nursing their pups.

No other large mammal has come so close to extinction and made such a rapid and successful recovery. In the 1800s, elephant seals were slaughtered for the oil rendered from their blubber, and by 1890 their population was reduced to an estimated 10 to 20 seals on one remote island off the coast of Mexico. With protection, however, the population had expanded enough by 1970 to resettle its former range from Baja California to Point Reyes.

Elephant seals began recolonizing Año Nuevo Island, now part of the UC Natural Reserve System, in the late 1950s, and scientists from the California Academy of Sciences started tagging seals there in the early 1960s.

“I started in 1968, but we actually had some tagging data from as early as 1961, and the research continues to the present day,” Le Boeuf said. “Long-term studies are essential for understanding the forces that shape an animal’s natural history, but they are very difficult to do. It’s exceptional that we have been able to study elephant seals continuously at the same site for over five decades. We have tracked more than 8,000 individual females throughout their lives and recorded their lifetime reproduction.”

Two things have made this possible. One is the easy accessibility of the colony at Año Nuevo, just 25 minutes north of UC Santa Cruz. In 1975, the growing rookery shifted from the island to the beach on the mainland at Año Nuevo State Reserve, where most of the elephant seal breeding activity now takes place, making it even more accessible for researchers.

The other important advantage is that elephant seals are exceptionally amenable to study. They are not easily disturbed and do not flee in fear of humans; individuals can be identified and followed for life and their reproductive success determined; animals can be tagged, weighed, and studied on the beach; and they can carry recording instruments for up to a year at sea without harmful effects on their behavior.

The development of time-depth recorders enabled Le Boeuf and his colleagues to begin learning about the lives of elephant seals at sea. Over time, researchers have developed ever more sophisticated tags for tracking the migrations of elephant seals and recording their behavior at sea and the physiological aspects of diving.

The UCSC elephant seal research program has been led for many years by Le Boeuf’s colleague Daniel Costa, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and director of the Institute of Marine Sciences. Over the years, hundreds of UCSC undergraduates and graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, staff scientists, and collaborators at other universities have participated in the research. More than 200 peer-reviewed research papers have been published on the elephant seals at the Año Nuevo rookery.

“We now know a great deal about this animal, more than we do about most other animals, and UCSC has been instrumental in this work,” Le Boeuf said.

Le Boeuf co-edited an earlier book on elephant seals—Elephant Seals: Population Ecology, Behavior, and Physiology (UC Press, 1994)—but much has been learned about these astonishing creatures in the years since then.

“I’m delighted to have been able to bring this new book together in this stage of my retirement,” he said.