Campus News

Nathaniel Deutsch’s ‘A Fortress in Brooklyn’ reveals provocative counter-history of American Jewry

A new book by UC Santa Cruz history professor Nathaniel Deutsch details how a group of determined Holocaust survivors survived in one of the roughest parts of New York City—reshaping the urban landscape of postwar Brooklyn.

A new book by UC Santa Cruz history professor Nathaniel Deutsch details how a group of determined Holocaust survivors survived in one of the roughest parts of New York City—reshaping the urban landscape of postwar Brooklyn and successfully dealing with the challenges of poverty, street crime, deindustrialization, and gentrification.

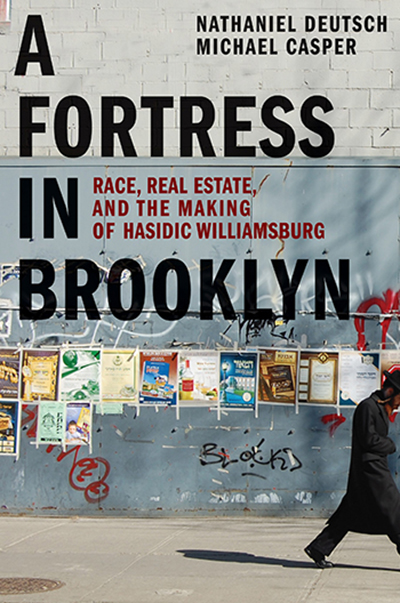

Co-authored with Michael Casper, A Fortress in Brooklyn: Race, Real Estate, and the Making of Hasidic Williamsburg is a deep study of the Hasidic community in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, one of the most intensely religious, politically savvy, little known, and misunderstood groups in the United States.

By showing how the embattled community rejected assimilation, while at the same time undergoing distinctive forms of Americanization and racialization, it offers a provocative counter-history of American Jewry, as well as a critical new look at how race, real estate, and religion intersected in the creation of the New York neighborhood.

“Most histories of American Jewry focus on the great waves of Jewish immigrants that arrived at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century and settled in neighborhoods like the Lower East Side in New York,” Deutsch noted. “Then, in the following decades and especially after World War II, most of these Jews and their descendants largely assimilated into mainstream American society, gave up speaking Yiddish, moved to the suburbs, and ceased to be Orthodox.

“By contrast, our book focuses on a smaller but, as we argue, very significant wave of Hasidic Jews who arrived in the United States after World War II, settled in Brooklyn, and refused to give up Yiddish, assimilate, or abandon Orthodoxy. Instead, they doubled down on what made them different and remained in New York, even as so many other Jews and white ethnics were abandoning the city in the 1960s and 70s.

“This is important today,” he added, “because Hasidim—and Haredim more generally—are by far the fastest growing demographic within the broader American Jewish community and if current trends continue, they will be a much more significant segment of the Jewish population in the United States, as well as in Israel, Great Britain, and elsewhere, in the near future. This has dramatic implications for the future of global Jewry.”

Deutsch and Casper researched the book for more than a decade, conducting interviews with Hasidic community members, as well as others in the neighborhood. They looked through years of Yiddish language newspapers and other media produced by the Hasidic community; Yiddish and Hebrew books published by Hasidim; and more recently, posts in online Hasidic chat rooms and websites (“despite the efforts of Hasidic community leaders to limit internet use among their members,” Deutsch noted).

The authors also examined federal census records, economic reports, government records, real estate publications, as well as numerous books and articles on the history of Williamsburg, New York City, urban studies, and gentrification.

In addition to being a history professor, Deutsch is also the Murray Baumgarten Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies, the faculty director of The Humanities Institute, and director of the Center for Jewish Studies at UC Santa Cruz. He explained why the Hasidic community in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is so deeply misunderstood.

“First, there is a long history of stereotyping Jews, in general, and Orthodox Jews, in particular. Because they signify Jewishness so explicitly and unequivocally in their dress, language, practices, and so on, Hasidim are often targeted with these stereotypes. Second, the Hasidic community in Williamsburg has long sought to segregate itself in order to protect its distinctive way of life—which it considers to be holy—from negative outside influences. This, in turn, has contributed to a lack of knowledge of the community by outsiders.”

“We hope that readers will see the Hasidic community in Williamsburg as dynamic, complex, and changing, even as its members have always stressed their loyalty to tradition,” Deutsch added. “Connected to that, we hope that readers will come to appreciate how much Hasidim in Williamsburg and in Brooklyn, more generally, have helped to shape their environment and, in the process, contributed significantly to the history of New York City.”