Campus News

Robert Bocking Stevens, fifth UCSC chancellor, dies at age 87

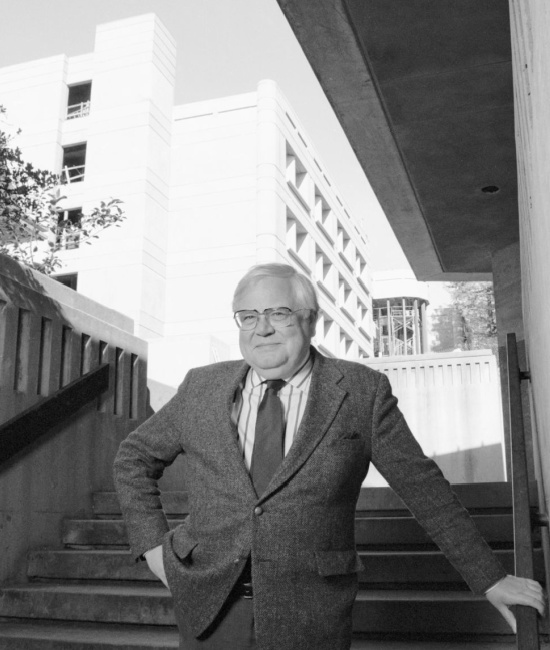

Robert Bocking Stevens, a legal scholar in England and the United States who served as the fifth chancellor of UC Santa Cruz, died Jan. 30 in Oxford, England, at age 87.

Robert Bocking Stevens, a legal scholar in England and the United States who served as the fifth chancellor of UC Santa Cruz, died Jan. 30 in Oxford, England, at age 87.

Stevens was named UCSC chancellor in June 1987 and held the post for four years. He later became Master of Pembroke College, Oxford University, until he retired in 2001.

At UC Santa Cruz, Stevens worked to increase student body diversity and accommodate growing demand for attendance while also working to repair town-gown relations over issues of university impact on traffic and housing. Stevens was in office when the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake struck and memorably allocated UC resources to aid recovery efforts in the city of Santa Cruz.

Stevens re-initiated planning for an engineering school by commissioning a faculty committee to study the idea. In 1991, Stevens submitted a proposal to the UC Office of the President, and a gift from the late Jack Baskin ultimately helped launch UCSC’s Baskin School of Engineering in 1997.

In an interview with the Regional Oral History Project shortly before he left Santa Cruz, Stevens said he was proud of his efforts to strengthen recruitment from underrepresented communities. “The fall I arrived 23 percent of our students were students of color. Next fall, (1991) 45 percent of our freshmen students will be students of color,” he said. “So there’s been a very dramatic change.”

He said he spent his first two years on campus purposefully working closely with the city to improve the town-gown relationship.

After the Oct. 17, 1989, Loma Prieta earthquake hit, ultimately causing about $7 million in damage on campus, Stevens directed UC resources to the city and county of Santa Cruz. “We didn’t need extra police and UCLA sent them so we lent police to the city. UCLA sent emergency medical teams whom we lent to the county,” Stevens said. “My goal was not to make any demands on the city at all. So we didn’t use their fire services, we didn’t use their police.”

Stevens was born June 8, 1933, in Leicester. He was educated at Oxford University and at Yale University, where he earned a masters of law. He first came to the United States at age 23 to take a fellowship at Northwestern University Law School.

Stevens later returned to England to become a law tutor at Keble College and launch a practice as a barrister. In 1960 Yale Law School offered him a position as an assistant professor, and he returned to the U.S. He became a U.S. citizen in 1971.

During much of his 16-year tenure at Yale, Stevens served as a legal adviser to the Commission on East African Cooperation in Nairobi, and later advised a successor organization, helping to negotiate agreements between Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and their neighbors. He taught his first course in legal history at Yale and the subject became the focus of his research.

Before coming to UC Santa Cruz, from 1978 until 1987, he served as president of Haverford College. Earlier, from 1976 to 1978, he was provost and professor of law and history at Tulane University. He also taught at Oxford University, the London School of Economics, Stanford University, and the University of East Africa.

In his interview with Randall Jarrell of the Regional Oral History Project, which he described as a “debriefing” after he announced his resignation, Stevens was very frank in admitting that he knew little about UC Santa Cruz before he was appointed chancellor. At the time he was also in the running for the top jobs at Case Western University, the University of Essex, and Dartmouth College.

He described a secretive interview process during which he first visited the campus and was told to say, if asked, that he was the brother of the person leading the tour. He said he took the job because he was impressed by the campus and its small college structure, and he and his wife liked Northern California.

Stevens accepted the job in the spring of 1987, succeeding Robert Sinsheimer. He was followed by Karl Pister.

Stevens wrote more than half a dozen books, including In Search of Justice (1968), Welfare Medicine in America (1974), Law Schools: Legal Education in America: 1850-1960, (1983) and The English Judges (2002).

He is survived by his wife, Kathie, three children — two from an earlier marriage — and two grandchildren. His youngest, Robin, was born in Santa Cruz when Stevens was chancellor and is now an author of fiction for children.