Rain falls lightly on the ocean’s surface. Marine mammals chirp and squeal as they swim along. The pounding of surf along a distant shoreline heaves and thumps with metronomic regularity. These are the sounds that most of us associate with the marine environment. But this soundtrack of a healthy ocean no longer reflects the acoustic environment of today’s ocean, plagued with human-created noise.

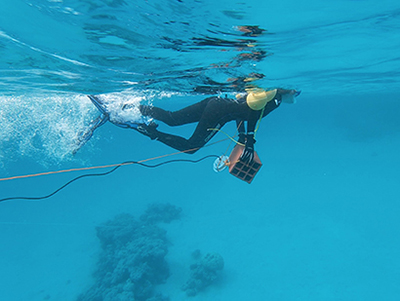

A global team of researchers set out to understand how man-made noise affects wildlife in the oceans, from invertebrates to whales, and found overwhelming evidence that marine fauna and their ecosystems are negatively impacted by noise, which disrupts their behavior, physiology, and reproduction, and can even cause mortality. The scientists call for human-induced noise to be considered a prevalent stressor at the global scale and for policy to be developed to mitigate its effects.

“While there is a lot of concern now about anthropogenic effects on the global environment, most of the attention has been focused on climate change and ocean acidification. We wanted to get people to recognize that noise needs to be part of that discussion,” said Daniel Costa, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and director of the Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS) at UC Santa Cruz.

Costa was part of a small group of marine scientists who came together in 2019 to discuss ocean noise at a meeting organized by Carlos M. Duarte, distinguished professor at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia. After the initial discussions, they recruited a broader group of scientists, all leaders in their fields, and conducted a thorough review of the issue.

Their findings, published February 4 in Science, are eye-opening as to the global prevalence and intensity of the impacts of ocean noise. Since the industrial revolution, humans have made the planet, and the oceans in particular, noisier through fishing, shipping, infrastructure development, and more, while also silencing the sounds from marine animals that once dominated the pristine ocean.

The deterioration of habitats such as coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and kelp beds due to climate change and other human pressures has further silenced their characteristic sounds—the soundtrack of a healthy ocean—which guide the larvae of fish and other animals drifting at sea into finding and settling on their habitats. The call home is no longer audible for many ecosystems and regions.

The Anthropocene marine environment, according to the researchers, is polluted by man-made acoustic phenomena, and should therefore be restored along sonic dimensions, as well as along more traditional chemical and climatic ones. Yet, current frameworks to improve ocean health ignore the need to mitigate noise as a pre-requisite for a healthy ocean.

“The good news is there actually is a way forward, and many of the solutions are coincident with carbon reduction, such as electric engines for ships,” Costa said. “We have tools to deal with sound, and unlike many other pollutants it is not persistent. Once you turn off the source, it’s gone.”

Costa, who has been studying underwater noise for several decades, noted that other researchers at UCSC’s Institute of Marine Sciences are also studying the effects of ocean noise on marine mammals, including Colleen Reichmuth, Ari Friedlaender, and Terrie Williams.

The new study points to the rapid response of marine animals to the human lockdown under COVID-19 as evidence of the potential for rapid recovery from noise pollution.

Sound travels far, and quickly, underwater. And marine animals are sensitive to sound, which they use as a prominent sensorial signal guiding all aspects of their behavior and ecology. “This makes the ocean soundscape one of the most important, and perhaps under-appreciated, aspects of the marine environment,” the study states. The authors hope the evidence presented in the paper will “prompt management actions...to reduce noise levels in the ocean, thereby allowing marine animals to re-establish their use of ocean sound.”

The team set out to document the impact of noise on marine animals and on marine ecosystems around the world. They assessed the evidence contained across more than 10,000 papers to consolidate compelling evidence that man-made noise impacts marine life from invertebrates to whales across multiple levels, from behavior to physiology.

“This unprecedented effort, involving a major tour-de-force, has shown the overwhelming evidence for the prevalence of impacts from human-induced noise on marine animals, to the point that the urgency of taking action can no longer be ignored,” said coauthor Michelle Havlik, a doctoral student at KAUST.

“The deep, dark ocean is conceived as a distant, remote ecosystem, even by marine scientists,” Duarte said. “However, as I was listening, years ago, to a hydrophone recording acquired off the U.S. West Coast, I was surprised to hear the clear sound of rain falling on the surface as the dominant sound in the deep-sea ocean environment. I then realized how acoustically-connected the ocean surface, where most human noise is generated, is to the deep sea; just 1,000 meters, less than 1 second apart!”

The takeaway of the review is that “mitigating the impacts of noise from human activities on marine life is key to achieving a healthier ocean.” The study identifies a number of actions that may come at a cost but are relatively easy to implement to improve the ocean soundscape and, in doing so, enable the recovery of marine life and the goal of a sustainable use of the ocean.

The coauthors of the paper include scientists from Saudi Arabia, Denmark, United States, United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Norway, and Canada.