Campus News

Troupe dynamic

UC Santa Cruz’s African American Theater Arts Troupe, which is celebrating its 30-year anniversary, has not only staged plays but also taken up works that deal with issues of race, injustice, and discrimination; brought its performances into the community; and awarded more than $100,000 in scholarships.

Most stories about the history of a theater company don’t start on a football field, but that’s how the 30-year saga of UC Santa Cruz’s African American Theater Arts Troupe (AATAT) begins.

According to Don Williams, founder and artistic director of AATAT, he was a skinny little kid in Michigan when he decided to try out for a middle school football team. Most of the boys were bigger and older than Williams, he said, but he practiced hard, and when it came time to find out if he’d made the squad—the coach said if a player opened his locker on a certain day and found equipment, he was in—Williams fully expected to be on the team.

On the appointed day, he flung open his locker. It was empty.

Instead of giving up, however, Williams tugged on a mismatched pair of old thigh pads and half-broken shoulder pads he found in a corner, pulled on a jersey, and slipped onto the field. He tried to hide behind some of the bigger guys, he said, but the coach spotted him and ordered him to take off his jersey.

“So when he sees the crazy stuff I had on, a tear comes to his eye and he says, ‘This boy wants to play football,’” Williams remembered. “That was a turning point in my life. It came to me then I could do anything I wanted to do if I applied myself and went for it. I never lost that.”

Which is why, when a few African American theater arts students approached him on campus 30 years ago and described their feelings of isolation and how they saw few stories that reflected themselves in the curriculum they studied, Williams felt that same determination. Even though he was doing technical work for the department and had no funding besides his own wallet, he agreed to start an African American theater troupe.

Since then, AATAT—the only student African American theater troupe in the University of California system—has staged plays by African American playwrights like Pulitzer Prize–winner August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone and Blues for an Alabama Sky by Pearl Cleage, as well as taken up works that deal with issues of race, injustice, and discrimination. It has awarded more than $100,000 in scholarships, has brought its performances into the community, and has amassed a cadre of devoted alumni.

“I think AATAT is so much more than a student group,” said Ted Warburton, interim dean of the arts at UC Santa Cruz. “It is a spiritual home, a place of belonging for our students of color who oftentimes express real feelings of being unmoored or excluded. It’s also a place where Don inspires students not only to express themselves but also to take on leadership roles.”

Creating the dream

Williams’s love for the theater started with a high school talent show, but he cut his production teeth in Los Angeles, working with actor Ted Lange (from The Love Boat) and Nick Stewart, founder of the Ebony Showcase Theatre. He’d founded a theater troupe at Michigan State University, where he got his undergraduate degree, pursued an M.F.A. in directing at the University of Southern California, and knew exactly the work he faced to stage a theater production on campus.

He convinced other African American students—10 in all—to join the group that first year and picked the play, Ceremonies in Dark Old Men by Lonne Elder III, which deals with issues of Black manhood, family, and racism in America. He bankrolled the production himself, appropriating old props and costumes from the Theater Arts Department and convincing a barber in town to lend him a barber’s chair, which is the focal point of the play. The students knew they would earn no credits but spent hours rehearsing.

The play was offered for three nights at the Stevenson Events Center. Tickets were free. The place was packed.

“We raised $1,500 in donations, and I asked the audience if they wanted to see this happen again and they cheered,” Williams said. “So, the next year, I did the play, The Amen Corner by James Baldwin.” The play deals with the role of the church in an African American family and the effects of poverty brought on by racial prejudice.

“A lot of Black students come up in the church,” Williams said, “so Amen Corner was a natural extension of that.”

Even then, the troupe was becoming a family for African American students, who made up a small part of the campus population. By 2019, African American students were still only 4.3 percent of university enrollment. Membership in the troupe has ranged from 15 to 40 in any given year.

“A lot of (Black students) felt like they were isolated,” Williams said. “You might find yourself in a dorm and you were the only one on the floor who was Black. You might be on campus a whole year and know only two or three Black people. That makes it hard on students, especially if you come from L.A. or Oakland where you are used to seeing reflections of yourself all around you.”

Soon, his wife was cooking meals for the troupe and some troupe members joined Williams at his church, he said.

“My wife is a good cook and she would make real soul food for them. The students would request her chili and her mac ‘n’ cheese,” Williams said. Members of Williams’s church even pitched in.

Momentum builds

“That second year, I felt the momentum building,” said Eric Jackson-Scott, M.D. (Rachel Carson ’95, chemistry), an occupational medicine physician who played the role of Theopolis in AATAT’s first play, Ceremonies in Dark Old Men. “The excitement and enthusiasm started to become something bigger. It was the natural evolution of something spectacular.”

In 1995, AATAT became a 5-unit class, and Williams was released from part of his technical job to direct the program. Funding was still problematic but the plays rolled on: Streamers by David Rabe, Fences by August Wilson, and the gospel musical Tambourines to Glory, with music by Langston Hughes and Jobe Huntley. Money raised from the plays was turned into four scholarships given to students each year.

Niketa Calame-Harris (Oakes ’02, theater arts), an actor and film producer best known for voicing Young Nala in Disney’s 1994 animated film The Lion King, remembered her AATAT role in Before It Hits Home by Cheryl West, which dealt with the AIDS crisis and discrimination against gay men.

“After our play closed, the rate of students getting tested for AIDS and STDs (sexually transmitted diseases) went up,” Calame-Harris said. “That was really cool to me. It showed me how art can inform and impact life.”

Williams also believed it was important to connect the community to these plays. The troupe has presented its works at the Louden Nelson Community Center in downtown Santa Cruz, at numerous high schools, and at Monterey Peninsula College.

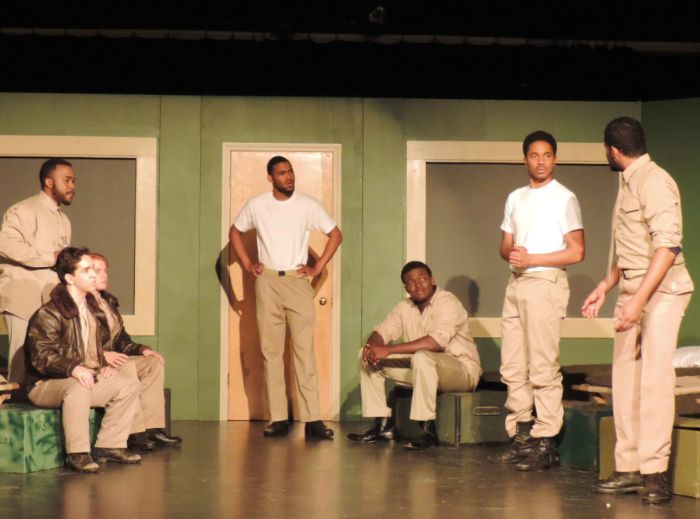

When AATAT performed A Soldier’s Play by Pulitzer Prize–winner Charles Fuller, which is set in 1944 and deals with the murder of a Black sergeant on an Army base, Williams invited to the performance two veterans of an all-Black Army troop, the 54th Coast Artillery Regiment. The regiment was stationed in Santa Cruz during WWII to guard against enemy attack and, according to accounts of the time, faced discrimination from some hostile townspeople. After the performance, Williams talked about issues raised in the play and introduced the two men, recounting their service and weaving the threads of the play with their lives.

“I made them honorary members of the theater troupe,” Williams said.

Those after-play dialogues are a regular part of AATAT performances, and so is the student research into topics that underlie each play, according to Williams. The result, said Williams, is that students often begin to not only find themselves and their voice but also feel they can assert their presence.

“When students go through that drill, they come out with a whole different mindset,” Williams said.

“The theater is grounded in hands-on experience and emotional connections,” Warburton said. “Don is producing, in powerful ways, a positive change that combats racism and creates a shared responsibility for sustaining that change now and into the future.”

You’re all right

Ask AATAT alumni about Williams (“Papa Don,” as he is known to them) and they’ll describe him as energetic, positive-minded, dedicated, and devoted to student leadership. They’ll also recall his trademark sayings: “Uplift one higher than yourself,” “You have to believe in some things you can’t see,” and his most famous: “I don’t care what others say about you, you’re all right with me.”

“Don taught me time management, leadership skills, communication, and belief in the possible and the impossible,” Jackson-Scott said.

On the phone, Williams rolls out his tales like the born storyteller he is.

“In Africa, they have this bird [a metaphorical symbol] called Sankofa whose head faces in one direction with his feet pointed in the other,” Williams said. “The idea is that in order to understand your future, you must have an understanding of your past. That principle has been with me all my life. I have always wanted to do something with substance that reflects my culture. I’m really focused on trying to teach students and the community that we have a rich history behind ourselves.

“You can’t,” he said, “just tap into the nightly news and think you understand Black people, but I can create a stage and tell you some of those stories” to help you see and feel and hear that experience.

It’s what he and the troupe have been doing for three decades now.

AATAT’s Honoring Our Roots, Uplifting Black Voices 30th anniversary gala will be on Feb. 20, from 6–8 p.m. RSVP on the event website.