Campus News

High-fidelity record of Earth’s climate history puts current changes in context

A continuous record of the past 66 million years shows natural climate variability due to changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun is much smaller than projected future warming due to greenhouse gas emissions.

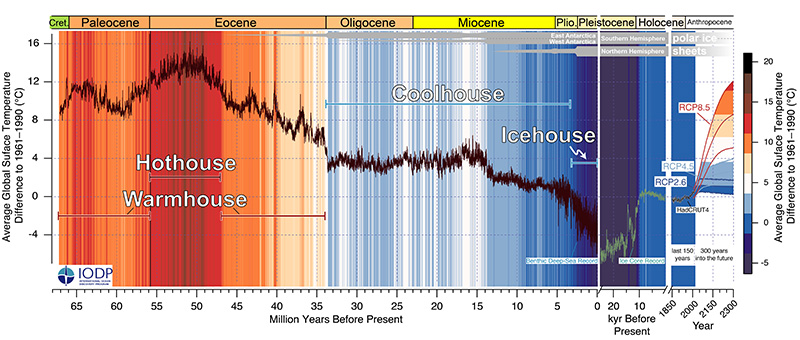

For the first time, climate scientists have compiled a continuous, high-fidelity record of variations in Earth’s climate extending 66 million years into the past. The record reveals four distinctive climate states, which the researchers dubbed Hothouse, Warmhouse, Coolhouse, and Icehouse.

These major climate states persisted for millions and sometimes tens of millions of years, and within each one the climate shows rhythmic variations corresponding to changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun. But each climate state has a distinctive response to orbital variations, which drive relatively small changes in global temperatures compared with the dramatic shifts between different climate states.

The new findings, published September 10 in Science, are the result of decades of work and a large international collaboration. The challenge was to determine past climate variations on a time scale fine enough to see the variability attributable to orbital variations (in the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit around the sun and the precession and tilt of its rotational axis).

“We’ve known for a long time that the glacial-interglacial cycles are paced by changes in Earth’s orbit, which alter the amount of solar energy reaching Earth’s surface, and astronomers have been computing these orbital variations back in time,” explained coauthor James Zachos, distinguished professor of Earth and planetary sciences and Ida Benson Lynn Professor of Ocean Health at UC Santa Cruz.

“As we reconstructed past climates, we could see long-term coarse changes quite well. We also knew there should be finer-scale rhythmic variability due to orbital variations, but for a long time it was considered impossible to recover that signal,” Zachos said. “Now that we have succeeded in capturing the natural climate variability, we can see that the projected anthropogenic warming will be much greater than that.”

Icehouse

For the past 3 million years, Earth’s climate has been in an Icehouse state characterized by alternating glacial and interglacial periods. Modern humans evolved during this time, but greenhouse gas emissions and other human activities are now driving the planet toward the Warmhouse and Hothouse climate states not seen since the Eocene epoch, which ended about 34 million years ago. During the early Eocene, there were no polar ice caps, and average global temperatures were 9 to 14 degrees Celsius higher than today.

“The IPCC projections for 2300 in the ‘business-as-usual’ scenario will potentially bring global temperature to a level the planet has not seen in 50 million years,” Zachos said.

Critical to compiling the new climate record was getting high-quality sediment cores from deep ocean basins through the international Ocean Drilling Program (ODP, later the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, IODP, succeeded in 2013 by the International Ocean Discovery Program). Signatures of past climates are recorded in the shells of microscopic plankton (called foraminifera) preserved in the seafloor sediments. After analyzing the sediment cores, researchers then had to develop an “astrochronology” by matching the climate variations recorded in sediment layers with variations in Earth’s orbit (known as Milankovitch cycles).

“The community figured out how to extend this strategy to older time intervals in the mid-1990s,” said Zachos, who led a study published in 2001 in Science that showed the climate response to orbital variations for a 5-million-year period covering the transition from the Oligocene epoch to the Miocene, about 25 million years ago.

“That changed everything, because if we could do that, we knew we could go all the way back to maybe 66 million years ago and put these transient events and major transitions in Earth’s climate in the context of orbital-scale variations,” he said.

Sediment cores

Zachos has collaborated for years with lead author Thomas Westerhold at the University of Bremen Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (MARUM) in Germany, which houses a vast repository of sediment cores. The Bremen lab along with Zachos’s group at UCSC generated much of the new data for the older part of the record.

Westerhold oversaw a critical step, splicing together overlapping segments of the climate record obtained from sediment cores from different parts of the world. “It’s a tedious process to assemble this long megasplice of climate records, and we also wanted to replicate the records with separate sediment cores to verify the signals, so this was a big effort of the international community working together,” Zachos said.

Now that they have compiled a continuous, astronomically dated climate record of the past 66 million years, the researchers can see that the climate’s response to orbital variations depends on factors such as greenhouse gas levels and the extent of polar ice sheets.

“In an extreme greenhouse world with no ice, there won’t be any feedbacks involving the ice sheets, and that changes the dynamics of the climate,” Zachos explained.

Greenhouse gas levels

Most of the major climate transitions in the past 66 million years have been associated with changes in greenhouse gas levels. Zachos has done extensive research on the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), for example, showing that this episode of rapid global warming, which drove the climate into a Hothouse state, was associated with a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere. Similarly, in the late Eocene, as atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were dropping, ice sheets began to form in Antarctica and the climate transitioned to a Coolhouse state.

“The climate can become unstable when it’s nearing one of these transitions, and we see more deterministic responses to orbital forcing, so that’s something we would like to better understand,” Zachos said.

The new climate record provides a valuable framework for many areas of research, he added. It is not only useful for testing climate models, but also for geophysicists studying different aspects of Earth dynamics and paleontologists studying how changing environments drive the evolution of species.

“It’s a significant advance in Earth science, and a major legacy of the international Ocean Drilling Program,” Zachos said.

Coauthors Steven Bohaty, now at the University of Southampton, and Kate Littler, now at the University of Exeter, both worked with Zachos at UC Santa Cruz. The paper’s coauthors also include researchers at more than a dozen institutions around the world. This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC), European Union’s Horizon 2020 program, National Science Foundation of China, Netherlands Earth System Science Centre, and the U.S. National Science Foundation.