Campus News

Report exposes rampant illegal fishing in North Korean waters

Ground-breaking study reveals hundreds of vessels fishing illegally in one of the world’s most contested ocean regions, contravening UN sanctions and fueling overfishing.

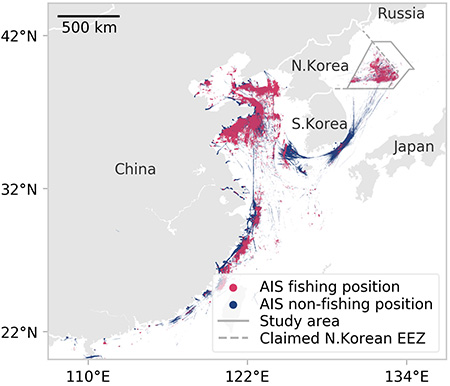

A new study reveals widespread illegal fishing by “dark fleets”—vessels that do not publicly broadcast their location or appear in public monitoring systems—operating in the waters between the Koreas, Japan, and Russia, some of the world’s most disputed and poorly-monitored waters.

Katherine Seto, assistant professor of environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz, is a coauthor of the study, published July 22 in the journal Science Advances. The investigation found more than 900 vessels of Chinese origin in 2017, and 700 in 2018, violated United Nations sanctions by fishing in North Korean waters. The vessels likely caught almost as much Pacific flying squid as Japan and South Korea combined—more than 160,000 metric tons worth over $440 million in 2017 and 2018.

“The scale of the fleet involved in this illegal fishing is about one-third the size of China’s entire distant-water fishing fleet. It is the largest known case of illegal fishing perpetrated by a single industrial fleet operating in another nation’s waters,” said Jaeyoon Park, senior data scientist at Global Fishing Watch and co-lead author of the study. “By synthesizing data from multiple satellite sensors, we created an unprecedented, robust picture of fishing activity in a notoriously opaque region.”

Following North Korea’s testing of ballistic missiles, the UN Security Council adopted resolutions in 2017 to sanction the country, and some of these prohibit foreign fishing.

The detected vessels originate from China and are assumed to be owned and operated by Chinese interests. However, because these vessels often do not carry appropriate papers, they are likely “three-no boats”—operating without official Chinese authority and with no registration, flag, or license.

Devastating impact

The study also found about 3,000 North Korean vessels fished illegally in Russian waters in 2018.

“Competition from the industrial Chinese trawlers is likely displacing the North Korean fishers, pushing them into neighboring Russian waters,” said study co-lead Jungsam Lee of the Korea Maritime Institute. “The North Koreans’ smaller wood boats are ill-equipped for this long-distance travel.”

Hundreds of North Korean boats have washed ashore on Japanese and Russian coasts in recent years. These incidents often involve starvation and deaths, and many fishing villages on North Korea’s eastern coast have become known as “widows’ villages.”

“The consequences of this shifting effort for North Korean small-scale fishers are profound, and represent an alarming and potentially growing human rights concern,” said UCSC’s Seto.

Rogue vessels

The study claims the previously unidentified vessels pose a huge challenge for squid stock management, with reported catches plummeting by 80 percent and 82 percent in South Korean and Japanese waters respectively since 2003. Pacific flying squid is South Korea’s top seafood by production value, one of the top five seafoods consumed in Japan and, until recent sanctions, was the third largest North Korean export.

Disagreement over boundaries in the waters between the Koreas, Japan and Russia have prevented joint fisheries management and hampered national efforts due to a lack of comprehensive stock assessments.

“Illegal fishing in these waters is a very serious matter in Japan, and the lack of shared data and management is a major challenge considering the critical importance of squid in the region,” said Masanori Miyahara, president of the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency. “We must face this challenge using the evidence provided by this study and other credible science.”

Satellite technologies

The study used four satellite technologies to illuminate the dark fleets. Automatic identification systems (AIS)—a collision avoidance system that constantly transmits a vessel’s location at sea—provide detailed vessel information, but are used by only a fraction of vessels. The study added radar images, which can identify large metal vessels and penetrate clouds; night-time imaging, which picks up the presence of fishing vessels using lights to attract catch or conduct operations at night; and high-resolution optical imagery, which offers the best visual “proof” of vessel activity and type. These technologies have never before been combined to publicly reveal the activities and estimated catches of entire fleets at this scale.

“These novel insights are now possible thanks to advances in machine learning and the rapidly growing volume of high-resolution, high-frequency imagery that was unavailable even a couple of years ago,” said David Kroodsma, research and innovation director at Global Fishing Watch and coauthor of the study. “We’ve shown we can track industrial fishing vessels that are not broadcasting their locations.”

Inter-Korean cooperation

The 2018 inter-Korean summits underlined the need to build peace through cooperation on the waters, create a joint fisheries management area, and address illegal fishing. Achieving these laudable ambitions will rely on unbiased information that all sides can trust.

“Global fisheries have long been dominated by a culture of unnecessary confidentiality and concealment. Achieving a comprehensive view of fishing activity is an important step toward truly sustainable and cooperative fisheries management, and satellite monitoring is a key part of the solution,” said coauthor Quentin Hanich of the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS) at the University of Wollongong. “This analysis represents the beginning of a new era in ocean management and transparency.”

The study was itself an example of international cooperation, with scientists from Japan, South Korea, Australia and the United States collaborating to reveal fishing activity in the region.