The International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition is much more than a contest. For many participants, the goal of iGEM is not winning a prize as much as it is using science to solve real-world problems. This is certainly true of the 16 students who make up the iGEM team at UC Santa Cruz.

“Here at UCSC, a major factor in how we choose our projects is their real-world application,” said Shayan Vahdani, a molecular, cell and developmental biology major and the team co-captain.

Originally designed for college students, iGEM currently includes teams from high school to overgrad (defined by iGEM as individuals over the age of 23) all over the world, and is training students to become responsible scientists as they design and orchestrate projects in synthetic biology.

Vahdani and his team are trying to create a heat-stable vaccine for Newcastle Disease, a common and highly infectious virus that can decimate entire flocks of chickens. If successful, the team’s research could make it easier for farmers in remote locations to vaccinate their chickens against disease, empowering local communities and aiding the fight against world hunger.

The students are working under the guidance of David Bernick, adjunct professor of biomolecular engineering in the Baskin School of Engineering, and graduate student Ryan Modlin. Newcastle Disease has been an especially persistent issue for nonprofit organizations like Heifer International, which works with small-scale farmers in developing nations to end hunger in their communities. Chickens need to be vaccinated frequently, and current vaccines need to be refrigerated, which can make getting them to rural areas a challenge.

“Having a vaccine that is temperature sensitive can be an issue for a lot of developing nations, especially where transportation is concerned,” said team member Preet Kaur, a student in biomolecular engineering.

The iGEM team’s goal is to create a more thermostable vaccine that can be stored at room temperature. To do this, they are using intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) that come from micro-animals called tardigrades (also known as “water bears”).

“Tardigrades can survive temperatures of up to 150°C and as low as -200°C, which is attributed mostly to their intrinsically disordered proteins,” Kaur said.

IDPs are unique to tardigrades and form gels that stabilize other proteins. When these gels dry, they form vitrified, or glass-like, solids instead of the typical crystalline solids formed by other proteins. Scientists think these vitrified solids protect the tardigrades from extreme temperatures. The iGEM team hopes to recreate this protective structure in its vaccine, and has named itself Vitrum (Latin for glass) to reflect this goal.

“Basically we’re taking the proteins that originate from tardigrades and putting them in solution with our vaccine. Hopefully, the vaccine will then create a glass-like structure around the virus, protecting it and making it thermostable,” Kaur explained.

An international collaboration

The science is only part of the iGEM experience. The program encourages research that is connected to the community and promotes teamwork and collaboration, not just within the team itself, but also with a broader global network. As part of their project, the team reached out to Heifer International to discuss the issue of the Newcastle virus.

Rita Ousterhout, a student majoring in molecular, cell and developmental biology, said meeting with several directors at Heifer International was one of the most rewarding experiences of the project. “We had a Skype conversation with them, and they offered to help us out however we ask for it,” she said. “It was really rewarding to hear how big an issue this is for them and have that collaboration.”

The Vitrum team has divided the work so that each student specializes in one aspect of the project, but they work together to help one another meet deadlines and accomplish their project’s goals. The team members come from a variety of backgrounds and majors, but they have managed to find common ground in their passion for scientific research.

“An amazing thing about iGEM is that we do a lot of great science, but we also build a family here and we get to know everyone. It’s great to have people around you who are interested in the same things and to be able to build friendships outside of science as well,” said Melody Azimi, a junior in biomolecular engineering and next year’s team captain.

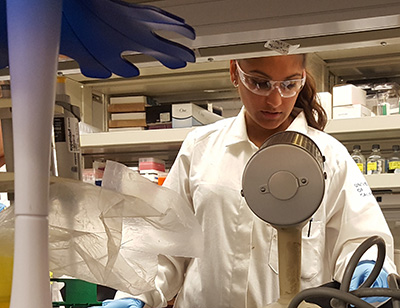

The work is not all glamorous, however. The iGEM team is selected in February and competes in October, giving students a very short window of time for completing the project, especially considering that they have to raise all of their own funds. Several students said they have sometimes stayed in the lab until 4 a.m. to meet a deadline or find a solution to a persistent problem, and Azimi said that “a lot of things in science just don’t work out.”

Even with the long hours and frustrating setbacks, the team members said they have found working on iGEM to be an incredibly rewarding experience. Vahdani stressed how amazing it has been working on a student-led team in which they are mostly left to figure things out for themselves. Other students agreed.

“I liked iGEM because it was the most hands-on research experience on campus, and you actually get to see an end product that could potentially be used in a real-world situation,” said Pierce.

Multiple members of the team said that they would encourage other students to get involved in research. “Make the most of the opportunities that UCSC offers,” Ousterhout urged. “There are so many great research labs on campus and I think that some go unnoticed because people are doing so many cool things on this campus.”

The team is still hard at work on their vaccine and will be attending the annual iGEM conference in Boston at the end of October, where they will present their project to other teams and a panel of judges. You can keep track of their progress on their website, https://2019.igem.org/Team:UCSC.