Campus News

Anthropologist Adrienne Zihlman publishes 450-page opus on ape anatomy and evolution

Anthropology Professor Emerita Adrienne Zihlman has published a 450-page volume that presents the “big picture” of what she has learned about human origins from her painstakingly thorough study of modern ape anatomy over the last four decades.

Dissection of Pogo

Adrienne Zihlman didn’t want to write a book just about skulls. Or teeth. Or femurs.

Zihlman made her mark on the study of human evolution by focusing on whole bodies, and she didn’t want to revert to the standard piecemeal approach just to please a publisher. So she wrote the book she wanted to write and published it herself.

The result is a 450-page volume that presents the “big picture” of what she has learned about human origins from her painstakingly thorough study of modern ape anatomy over the last four decades.

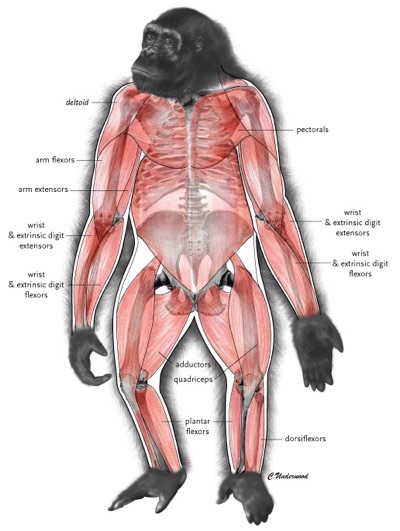

Not content with the study of fossils, Zihlman began early in her career to study the soft tissue of contemporary animals, hunting for clues to the mechanics of locomotion. Her book also takes a “whole animal” approach, presenting detailed analyses of bones, muscles, and tendons to showcase how all the parts work together.

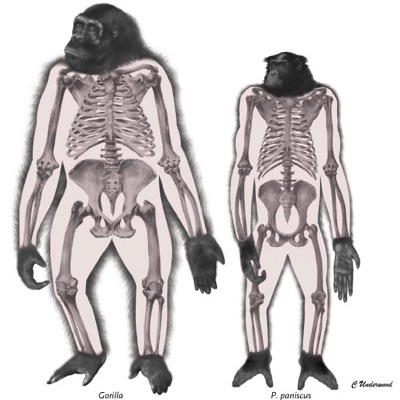

Ape Anatomy and Evolution is unlike conventional textbooks, which typically focus on one body part or one body system. Zihlman adds another layer of complexity by comparing the anatomy of the four major apes: gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and gibbons.

“I wanted to illustrate the idea that human evolution shares so much with the apes—and also give a counter to that by illustrating where the differences are,” said Zihlman, a professor emerita of anthropology who retired in 2012. Traditional anatomy books are “very narrow, very technical, very boring,” she added. “You never get a sense of the whole animal. My underlying principle was a desire to understand their evolution and adaptation, and to give readers a sense of where the animals lived, how they moved, and what their particular ecological niche was.”

Zihlman and her long-time collaborator Carol E. Underwood spent more than a decade working on the book; Underwood created dozens of lavish illustrations and graphics that are featured throughout the volume. “It’s a really different book,” said Zihlman. “It was risky. A colleague said we’re doing something so different that it’s going to take a while for it to be successful.”

Zihlman, who joined the faculty in 1967, was drawn to the challenge by what she believes it offers readers—students, researchers, and a lay audience, as well. “After all this work, I feel I’m really beginning to understand the apes and the lessons they have to tell us,” she said. “I can’t help but always be the educator and try to put it all together.”

The muscles and bones associated with locomotion account for two-thirds of an ape’s body mass. Much of the study of evolution has focused on the skeleton—skull, teeth, and limb bones—which adds up to less than 15%, she said.

“Paleontologists use two or three bones to reconstruct locomotion, which is limited,” said Zihlman. “You need the whole skeleton, and the muscles, and the locomotion anatomy, and the range of variation that you only get by looking at numerous individuals.”

Bwana, Zihlman’s first gorilla

Zihlman’s investigation of primate anatomy really took off with Bwana, a male silverback gorilla that died in captivity in 1994 at the San Francisco Zoo. She could hardly believe her good fortune when she was offered the body to dissect.

Word of Zihlman’s unique approach spread over time, and she eventually acquired and dissected more than 20 gorillas, 20 pygmy chimpanzees, nearly 30 gibbons, and several orangutans. The lab where she did this pathbreaking work has since been named the Adrienne Zihlman Laboratory in honor of her contributions.

Zihlman made the most of each opportunity, and she generated an unprecedented amount of information about each animal: bone measurements and soft tissue analysis, which she was often able to combine with detailed zoo records of the life history of individual animals. “It’s so rare to have all that about one individual,” she noted. “People do individual muscle weights, but they don’t study the bone. Or they study the bone but ignore the soft tissue. Or they don’t know about injuries suffered during an animal’s lifetime, and how it might permanently affect the animal’s anatomy.”

Similarities and differences

Putting it all together allowed Zihlman to see important patterns.

“It looks like male apes and female apes have a lot in common with each other across species,” said Zihlman. “Males are always heavier than females, and they always have more muscle. They’re bigger in the upper body.”

What accounts for the difference? Females’ body systems mature earlier than males, so females cease growing—their bones fuse and they reach adult weight sooner, whereas males continue to add muscle before their bones fully fuse. “We’ve known that, but to see the sex differences patterned across the ape species was wonderful,” she said.

Endlessly fascinated by anatomy, Zihlman said species differences between gorillas and orangutans in bone length and limb mass of arms and hands align with behavior: “Orangutans have more muscle mass in their hands and feet, because of how they move solely in the trees. They don’t knuckle-walk on the ground, like gorillas do. Orangutans are all about clambering through the trees, grasping onto branches and vines,” she said, adding, “You can start connecting the signature of distinctive orangutan anatomy with the behavior to better understand the patterns and unique adaptations.”

Conventional anatomical literature is too “reductionist and piecemeal,” making it difficult to understand an animal’s locomotor potential, according to Zihlman.

“Knowing the anatomy makes the behaviors more understandable”

Even students and researchers who study primates in the field benefit from a deep understanding of anatomy, said Zihlman.

“If you know what the underlying body structure is, knowing the anatomy makes the behaviors more understandable when apes move—their postures while feeding, why they follow certain pathways through the forest, climb or leap across the canopy,” she said. “In a very accessible way, this book shows field researchers what their subjects are all about beneath the skin.”

Understanding anatomical structures and the possible range of locomotor behaviors sheds light on each group’s adaptations and how species can live together—”how chimpanzees have adjusted to compete with gorillas, why gibbons don’t directly compete with closely related siamangs,” added Zihlman.

It also enriches the story of human origins. Molecular data has established chimpanzees as our closest relative, but Zihlman develops the physical evidence in the locomotor anatomy and behavior of the two chimpanzee species. Finally, Zihlman is delighted by the prospect of her work being part of the contemporary discussion of human origins, which encompasses ecology, evolution, new molecular data, and anatomy.

“It’s gratifying to make this information accessible,” said Zihlman, who also wrote The Human Evolution Coloring Book and co-edited The Evolving Female. “This book summarizes our methodology and decades of lab dissections, and we think it will be a useful teaching and learning tool for anthropology students, and professionals.”

That said, Zihlman’s work is far from done. “There’s a lot of original data in this book—but it’s not nearly what we’ve got.” Zihlman and Underwood are analyzing their data, developing new hypotheses about our fossil ancestors, and writing journal articles. And if that’s enough, Zihlman is already working on another book, this one more of a memoir about “adventures in science.”

—-

Ape Anatomy and Evolution is available through Amazon.