Campus News

Researchers enlist citizen scientists to count animals on Año Nuevo Island

Volunteers will use drone photos uploaded to the Zooniverse platform to count birds, seals, and sea lions for an unprecedented census of the island.

UC Santa Cruz researchers are inviting citizen scientists to help achieve the first comprehensive counts of the thousands of seals, sea lions, and seabirds on Año Nuevo Island, a rocky islet just off the coast from Año Nuevo State Park north of Santa Cruz.

The Año Nuevo Island animal count project (sealcount.com) launched on Wednesday, August 7, on the Zooniverse citizen science platform. Volunteers are needed to help identify and count the animals in a vast trove of aerial photographs of the island and its inhabitants.

“Access to the island is limited to a small number of researchers each year, so we see this as an exciting opportunity to share the magic of Año Nuevo Island with the public,” said UCSC biologist Roxanne Beltran.

Año Nuevo Island, part of the UC Natural Reserve System’s Año Nuevo Reserve, is an important breeding site for northern elephant seals, California sea lions, and other marine mammals, and for seabirds such as cormorants and gulls. Long-running research projects at the island and nearby sites on the mainland include elephant seal studies led by Daniel Costa, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology (EEB) and director of the Institute of Marine Sciences. Beltran, a postdoctoral fellow in Costa’s lab, said annual census counts for individual species on the island have always been a challenge.

“The traditional method is to use a hand-held clicker, and you can imagine looking at a beach packed with moving sea lions, with birds attacking your head, and trying to get an accurate count. It’s hard,” she said.

NOAA conducts manned-aircraft surveys of the seals and sea lions once per year (if conditions allow), and Oikonos, a non-profit conservation organization, does seabird censuses. Improving the accuracy and frequency of surveys is key to tackling time-sensitive research questions, Beltran said.

Drone images

In 2016, reserve director Patrick Robinson obtained research permits to start flying a drone over the island, taking aerial photographs of the entire island every couple of weeks throughout the year for four years. The result is a huge database of about 50,000 photos with the potential to yield valuable information about how the animal populations on the island fluctuate over time.

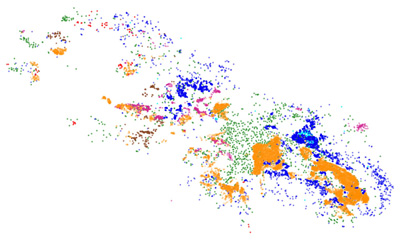

UCSC undergraduate Sarah Wood has taken charge of the Zooniverse project as part of her full-time summer internship with Costa’s lab through the CAMINO program. Wood’s tasks included creating the project’s Zooniverse web site, as well as processing all the images and preparing them for the Zooniverse platform. This involved stitching together all the overlapping drone photos taken on a particular day into one seamless image of the entire island. Then each complete image of the island had to be broken down into manageable sections for the volunteers’ animal counts.

“We are hoping to find enough volunteers to count each animal in more than 50 sets of drone photos,” Beltran said. “In an image from just one day of this year, Sarah counted over 18,000 animals, including more than 4,000 California sea lions and 12,000 cormorants.”

Volunteers can choose between birds and marine mammals for their counts, and there are online tutorials to teach them how to identify different species. “Our goal is to get counts, but we want to educate citizen scientists as well, so Sarah included some great natural history content on the web page,” Beltran said.

The population counts for each species will give researchers important insight into the health of the populations and how they change seasonally and from year to year. In addition, when the volunteers click on an animal in an image, it gives researchers the coordinates for that animal’s location, so they can study things like how the animals clump together, how the birds space out their nests, and so on.

Initially, the researchers investigated the potential for using artificial intelligence (AI) to analyze the images and automate the population counts. But after consulting with specialists, they realized it would probably not work for this project.

“The variability between individual sea lions, for example, is enormous in terms of shape, size, and color, so counting individuals is a task that is better suited for humans, at least for now,” Beltran said.