Campus News

New book reframes activism of Native leaders who sowed seeds of Red Power Movement

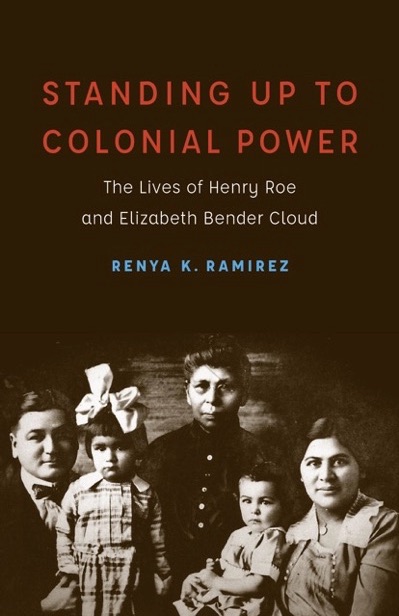

In her new book, Anthropology Professor Renya Ramirez portrays her grandparents, legendary Native leaders Henry and Elizabeth Cloud, as “Christian warriors” whose activism sowed the seeds of what would come to be known as the Red Power Movement.

As the youngest grandchild of legendary Native leaders Henry and Elizabeth Cloud, anthropology professor Renya Ramirez was well-positioned personally and professionally to fill in the historical record regarding their contributions.

Yet even she was surprised by what she learned.

In her new book, Standing Up to Colonial Power, Ramirez portrays Henry and Elizabeth as “Christian warriors,” individuals who dedicated their lives to educating and empowering Native youth, preserving Native culture, and holding the federal government accountable to tribal communities across the country. Decades before Wounded Knee and the occupation of Alcatraz, their activism sowed the seeds of what would come to be known as the Red Power Movement.

Henry Roe Cloud was a well-known policy maker in the Office of Indian Affairs who coauthored the Meriam Report of 1928, which laid the foundation for the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. He and Elizabeth Bender Cloud co-directed the American Indian Institute, a Christian college-prep boarding school for Native youth in Wichita, Kansas, that combined the traditions of Native education with a college-prep curriculum.

Ramirez suspects that the Clouds’ Christian faith and their successful navigation of the highest levels of government prompted historians to pigeonhole them as sellouts who abandoned their Native identities.

Not so, says Ramirez.

“They fought back against the government, they fought for tribal sovereignty, and they built support for tribal identity,” says Ramirez, author of Standing Up to Colonial Power: The Lives of Henry Roe and Elizabeth Bender Cloud (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). “My grandparents were actually doing work that led to the Red Power Movement.”

Defying settler colonialism

Both born in the 1880s, Henry and Elizabeth’s life stories span an extraordinary period during which government policy focused on shattering tribal identity and Native connections to the land.

Born and raised in Winnebago, Nebraska, Henry was a member of the Ho-Chunk tribe and became the first full-blooded Native graduate of Yale University. Elizabeth, an Ojibwe, was born on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. When they met as young adults, they forged a union as partners in Native activism that would endure until Henry’s death in 1950.

Both were forcibly separated from their families as young children to attend federal boarding schools where physical abuse was rampant, according to Ramirez. “It was kidnapping, really,” said Ramirez. “Native children were treated like they were incarcerated.”

Henry converted to Christianity during boarding school, and the course of his life changed when a teacher encouraged him to go to a college preparatory school. At Yale, he met Mary and Walter Roe, white missionaries who informally adopted him and whose surname he took as his middle name. He was later ordained as a Presbyterian minister. Elizabeth, too, was Christian. “They were being both activists and devout Christians,” said Ramirez.

Henry and Elizabeth’s advocacy on behalf of Natives focused on education, and they co-led the American Indian Institute to prepare students to become leaders of tribal communities, said Ramirez.

“At the institute, they read Shakespeare, and Henry told Ho-Chunk stories,” she said. “They combined traditions of Native education with the college-prep curriculum: foreign language, history, English. They learned history from the Native perspective. Henry wanted to train Christian warriors and teach them to fight for justice for Native communities.”

“They were becoming Native and modern at the same time,” added Ramirez. “They were being educated to go back to their Native communities and fight the federal government, and to fight for their rights.”

Compiling the first family-tribal history

Ramirez’s account of her grandparents’ activism, which she calls a “family-tribal history,” is based on a combination of family and archival research. Ramirez, a member of the Winnebago tribe of Nebraska, delved into family records, gathered evidence of Native oral testimonies, conducted numerous interviews, and pored through the archives of the Yale Sterling Library, the Society of American Indians archives in Chicago, and the Presbyterian Historical Society.

Henry worked for the Office of Indian Affairs and the Brookings Institution, traveling widely to document the state of Native communities across the country. He focused on education, health, welfare, and their economic wellbeing. His work helped change government policy from one of assimilation to cultural pluralism, according to Ramirez. “Millions of acres were brought back to the communal reservation for tribes,” said Ramirez. “The goal was for Natives to have tribal councils and a relationship with the federal government.”

In 1947, Henry was named superintendent of the Umatilla reservation in Oregon—an attempt, Ramirez believes, to reduce his influence on federal policy. In Oregon, he fought for Native fishing rights and protested “Wild West shows” that promulgated the dominant narrative of colonial settlers overpowering Natives and relocating them to reservations, where they lived “happily ever after.” Elizabeth was active in the National Congress of American Indians and General Federation of Women’s Clubs. Once in Oregon, she continued advocating for education, encouraging women to go to college and become leaders of Native communities.

“This book honors a period of history from the beginning of the 20th century to the 1950s, when Elizabeth was organizing Native community gatherings that eventually led to the Red Power Movement,” said Ramirez. “It shows how my grandparents combined their Native and warrior identities and fought for tribal sovereignty and cultural citizenship to fully belong in this nation. I don’t think people have understood them, or seen how ahead of the time they were. Previous books completely missed all this.”

Henry and Elizabeth had five children, including their daughter Woesha Cloud North, who began compiling the family history but died before she was able to complete it. Her daughter, Ramirez, took up the challenge.

Ramirez invokes some Native wisdom as she describes her grandparents’ day-to-day lives.

“In order to do so well in high government circles, my grandparents had to be both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Indians,” said Ramirez. ” ‘Good’ Indians seem to be assimilating and acting white, while ‘bad’ Indians challenge assimilation and act Native. My grandparents were constantly shifting, which is part of being Native. You learn how to shape shift. We have a lot of stories about shape shifting—trickster stories about creatures taking different forms in different settings. There’s a lot of humor and creativity in these stories.”