Campus News

Researchers plant baby oysters at Elkhorn Slough

First attempt in California to restore native oysters through aquaculture is led by Kerstin Wasson, adjunct professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz.

On October 23, 2018, a new generation of Olympia oysters will settle into their home on the tidal mudflats of the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve. These oyster babies were raised at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories’ new Aquaculture Facility, with a grant from the Anthropocene Institute and support from California Sea Grant. This effort represents the first attempt to support native oyster restoration through aquaculture in the state of California.

Why were these juvenile oysters raised in the lab? Elkhorn Slough Reserve’s Research Coordinator Kerstin Wasson, who has been tracking natural recruitment of oysters in the estuary for the past decade, explained, “In all the years I’ve been monitoring, we only had a good crop of new juveniles appear twice, once in 2007 and once in 2012.” With the last successful event going back six years, Elkhorn Slough’s native oyster population is at real risk of disappearing entirely. Native American middens and paleo-ecological data reveal oysters have lived in the estuary for ten thousand years.

“I don’t want to lose them on my watch,” said Wasson, an adjunct professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz.

For the past decade, the Elkhorn Slough Reserve and Elkhorn Slough Foundation have been committed to conservation of the native Olympia oyster in Elkhorn Slough. Their goal is to ensure that this iconic bivalve thrives in this estuary as a legacy for future generations. In 2012, Wasson, along with Elkhorn Slough Reserve Biologist Susie Fork and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s Chela Zabin, deployed hundreds of clam shell reefs to provide habitat to native oysters, which need hard substrate that prevents them from being buried in the mud. That was a good settlement year, and the reefs soon supported thousands of new oysters. Since then, however, virtually no new recruits have appeared on these reefs or anywhere in the estuary.

The exact cause of the oysters’ reproductive failure is unknown. Wasson conducted a comparative study of oyster recruitment, published in the journal Ecology, collaborating with researchers along 2500 km (1,553 miles) of coastline. They found that estuaries with high failure rates tended to have especially small remaining oyster populations and strong marine influence, which can result in cold waters and larvae being swept out to sea rather than retained in the bay. The artificial mouth to Elkhorn Slough built in the 1940s to support Moss Landing Harbor has substantially increased marine influence to the estuary.

No matter what the cause, one clear solution was to raise native oyster spat in a hatchery, the way commercially grown, non-native oysters are produced all along this coast because waters are generally too cold for natural reproduction. Fortuitously, the timing was right: Moss Landing Marine Laboratories (MLML) was just in the process of developing aquaculture capability. Wasson and her former student Brent Hughes, who earned his Ph.D. at UC Santa Cruz and is now a professor at Sonoma State University, received a grant from the Anthropocene Institute to fund the aquaculture project.

“Part of this project is all about rescuing oysters, but also to place them in different areas where we can learn about their species interactions and possibly new areas for restoration,” Hughes said.

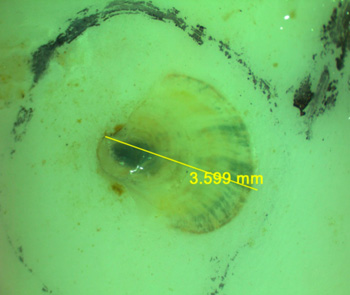

Led by Michael Graham, Scott Hamilton, and Luke Gardner, a team of students, staff, and researchers at MLML worked together to develop aquaculture techniques. Adult oysters were taken through a temperature regimen involving a steady increase of water temperature over a couple of weeks to stimulate sperm release necessary for egg fertilization. After larvae release from the female oysters, free swimming larvae were moved to separate rearing tanks until they were large enough, with eyespots and a mobile foot, to begin settling on native gaper clam shells as a settlement surface. Then followed months of laborious feeding with cultured microscopic algae.

“Raising oysters is a finicky business but we got them through,” said Luke Gardner, a California Sea Grant aquaculture specialist and MLML research faculty member.

Finally, about 2,500 fresh oyster recruits are ready for the real world — a number that represents about 10 times the number of live oysters in the part of the Elkhorn Slough Reserve where they will be transplanted.

On October 23, a team of Elkhorn Slough Reserve staff and volunteers will attach clam shells bearing newly settled oysters to wooden stakes, and put these out in the mudflats of the Reserve. Past data suggest that oysters, once settled, grow and survive quite well.

“Linking oyster restoration to aquaculture may be the answer to saving this species in Elkhorn Slough and other highly altered estuaries,” said reserve manager Dave Feliz, who manages Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), which owns the property.