Campus News

Community engagement enhances graduate education

Associate Professor Elliott Campbell and Professor Chris Benner co-taught a Spring Quarter class to connect first-year graduate students with environmental problems in the Salinas Valley Basin and to foster collaboration with off-campus stakeholders.

The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is an ongoing tragedy. Yet just down the highway from UC Santa Cruz, numerous communities in the Salinas Valley Basin lack access to affordable clean water.

In a new model of community engagement, Environmental Studies faculty are harnessing the talent of graduate students to help change that.

Associate Professor Elliott Campbell and Professor Chris Benner co-taught a Spring Quarter class to connect first-year graduate students with environmental problems in the region and to foster collaboration with off-campus stakeholders. Water in the Salinas Valley Basin is a persistent problem, and students examined the history and politics of who gets access to clean water, as well as the human impacts of inequities in the system.

“This isn’t just homework, it’s dealing with real problems,” said Campbell, the Gliessman Presidential Chair in Water Resources and Food Sustainability, who will co-teach the course, “Environmental Studies in Practice,” again next winter. “This is our way of building a longer-term commitment to community stakeholders.”

Students tackled the role of the Salinas Valley Basin Groundwater Sustainability Agency (SVBGWSA); how the delivery of safe drinking water to disadvantaged communities is governed; and the water and energy demands of strawberry production. By the end of the quarter, each team produced a report and gave a public presentation based on their research and community interactions.

By all accounts, it was a demanding, eye-opening, at times heart wrenching, deep dive into California water politics.

A changing landscape for water in California

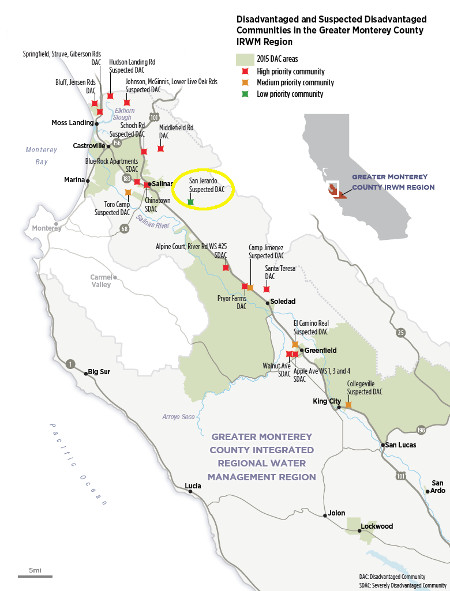

To explore and understand the forces shaping access to water for disadvantaged communities—a formal designation for areas that suffer from a combination of economic, health, and environmental burdens, Campbell and Benner renewed ties with members of the San Jerardo Housing Cooperative, a farmworker community southeast of Salinas that has struggled for almost 30 years to get clean water. In 2006, UCSC environmental studies undergraduates partnered with residents to document the health impacts of groundwater pollution in the cooperative.

About 250 people live in the cooperative, which was built to house farm workers who came to the U.S. from Mexico as part of the Bracero program. Fertilizer used on the surrounding fields has created nitrates that have contaminated one well after another. Polluted water has been linked to rashes and skin problems, including hair loss.

The newest well, installed by Monterey County in 2010, pumps clean water from two miles away, but the relatively small number of residents must bear the entire cost of the system. Some families pay $100 per month, while others still don’t trust the well water and choose instead to buy bottled water.

Horacio Amezquita, the general manager of San Jerardo, would like to see the county turn over operation of the water system to the cooperative, which he believes could run it more affordably.

And San Jerardo is not alone. Dozens of California communities, most of them low-income and predominantly Latino, are coping with water supplies that don’t meet current quality standards for drinking water. They truck in water or rely on expensive bottled water, said Campbell.

A new landmark state law mandates the “sustainable” use of all aquifers in California, stipulating that users can’t take out more water than accumulates naturally—a challenge for the critically overdrafted Salinas Basin.

Across the state, local jurisdictions are establishing new agencies to oversee decision making and the distribution of this contested resource, with representation from urban and rural water users, nonprofits, industry, disadvantaged communities, and others.

This landscape put issues of environmental justice at the center of the research, which is something the Environmental Studies Department wants to do, noted Benner, an urban political economist and director of the Everett Program for Technology and Social Change. And the community-engaged research approach recognizes that there are many “ways of knowing and learning about issues,” he said. “Scientific knowledge has a certain privileged power, but it also has blinders and limitations. Community-engaged research makes those connections.” The resulting projects were remarkably creative and interdisciplinary, blending quantitative and qualitative research, he said.

Documenting decades of struggle

The three-student team that focused on water governance built a web-based “timeline” to document what San Jerardo residents have gone through over the decades in their struggle to get access to clean drinking water. Most recently, the cooperative has petitioned the State Water Board to gain control of their water system, but it’s unclear if San Jerardo can meet the board’s requirements for reserve funds.

Doctoral student Azucena Lucatero was part of the timeline team, and she found herself drawn to the community’s story. “This was my first exposure to community-engaged research,” she said. “We wanted to use our position as student researchers with a bit of a platform through this class to do what we could to help them continue their struggle.”

Her team developed the timeline because they wanted to build the community’s capacity to continue documenting their struggle. “Storytelling is a huge part of how they’ve gotten outside resources, mobilized outside organizations, and gotten legislators to act on the issue,” she said.

Based on extensive interviews and archival research, the San Jerardo case study stands as a model for many other communities, said Campbell.

Many of these communities are invisible to the general public, so documenting this in a public way increases their visibility,” he said. It also highlights some of the factors that set San Jerardo apart from other communities, including having an engaged, bilingual general manager and nonprofit partners that have connected the cooperative to resources such as grants and journalists. Amezquita has lived at San Jerardo since 1979 and was an active partner with the graduate students.

“Some of these communities haven’t had clean drinking water since the 1980s,” said doctoral student Allyson Makuch, who also worked on the timeline. “Women are having miscarriages from carrying 5-gallon bottles of water.”

The pace of the 10-week course was demanding, and the focus on San Jerardo stoked a desire to make an “actual contribution,” said Makuch, who was drawn to UCSC’s Ph.D. program in part because of its interdisciplinary approach. “UCSC is interdisciplinary, with a strong social justice mission and a commitment to community-engaged research,” she said.

Lucatero described her “visceral, emotional response” to seeing people struggling, and her subsequent discovery of the “language, tools, and codified methods” of community-engaged research (CER). After the course ended, Lucatero attended a weeklong CER institute sponsored by the Everett Program, and the two experiences have secured her desire to learn more.

“San Jerardo is like the community where I grew up in Southern California,” she said. “That’s kind of why I want to do community-engaged research, to serve my community.

Power and influence, and strawberries

Water is a precious commodity across California, but the Salinas Valley is particularly hard hit, because agriculture extracts 95 percent of the groundwater in the area. The new state mandate for sustainable aquifer management pits the heavyweight agricultural industry against the needs of disadvantaged communities. The second group of graduate students examined “power and influence” within the Salinas Valley Basin Groundwater Sustainability Agency (SVBGSA), considering the interests that were represented and “following the money” to see how funding influences decision making. Not surprisingly, they identified agriculture’s strong influence over the agency’s decisions, which the group found were “unequally focused on water quantity over any other aspect of sustainable groundwater management.”

The third group of students did a case study of the “food-water-energy nexus” of the strawberry industry in the Salinas Valley. Despite its unstable water supply, California produces about 90 percent of the nation’s strawberries, an industry valued at more than $2 billion. The group considered the energy costs of pumping water to farms for irrigation and of transporting berries from fields to markets, as well as the water used to make fertilizers. This “life cycle” approach to resource use presents a more comprehensive picture of water use, as well as environmental impacts such as the production of greenhouse gas emissions, and it should be used in any attempt to sustainably manage state water resources, they concluded.

The spring class culminated with student presentations in the Monterey County Offices in Salinas that were attended by members of the SVBGSA, the general manager of the board, and technical advisers. Acknowledging that the reports were critical of many of the agency’s current policies and practices, Lucatero said being a graduate student made it easier to “speak truth to power,” because she doesn’t anticipate interacting with the officials again. It was harder to say goodbye to San Jerardo and return to her own research program, which is focused on insect biodiversity in urban gardens.

“You have to balance your own interests with the needs of the community,” she said. “Ten weeks is very, very short. We did the best we could. I hope it does help.”

Horacio Amezquita, manager of the San Jerardo Cooperative, said the students did an “amazing job delivering their message to the new Groundwater Sustainability Agency.” Representatives of the agriculture industry were skeptical of some aspects of the reports, but the message about the decades-long struggles of disadvantaged communities to get clean water came across loud and clear, he said. “A lot of disadvantaged communities don’t have clean water,” Amezquita added. “They’ve been left behind. No one is helping them get access to clean wells that would provide clean water to their homes.”

Partnering with community stakeholders

To ensure continuity and ongoing support for San Jerardo, Campbell will work with the same stakeholders next year: the San Jerardo Cooperative, the Salinas Valley Basin Groundwater Sustainability Agency, and others. Campbell will co-teach the class again next winter, teaming up with Brent Haddad, a professor of environmental studies who specializes in water issues and directs the Center for Integrated Water Research.

“We’ll have a new cohort of graduate students,” said Campbell. “Projects will be student-driven, with instructor expertise, but they’ll pick their own research questions.”

This approach to graduate education—integrating community-engaged research into the first-year experience—is challenging. It introduces students to theory and methodologies that may lie outside their expertise or research interests, and the pace is swift. Collaborating with stakeholders outside academia can be difficult, and this level of personal involvement may be new for some. But it is part of the full portfolio of research skills that support a diverse range of career goals, said Lori Kletzer, vice provost and dean of Graduate Studies.

“Training our students in community-engaged scholarship is valuable for those who are interested in academia, as well as those who plan to work in government, nonprofits, NGOs, policy, and advocacy,” said Kletzer. “This type of collaboration is a terrific complement to the interdisciplinary nature of environmental studies. It further distinguishes our graduates as they pursue their careers.”

It is also part of the public-service mission of the University of California, noted Campbell, adding, “As a public research university, we have a commitment to serve the people of this state.”