Campus News

New book by UC Santa Cruz arts professor examines cultural impact of video games

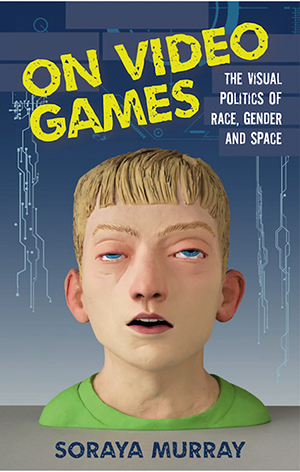

In her new book, ‘On Video Games: The Visual Politics of Race, Gender and Space,’ UC Santa Cruz professor Soraya Murray goes beyond the technical discussions of games and instead offers a deep dive into their cultural dimensions.

In her new book, On Video Games: The Visual Politics of Race, Gender and Space, UC Santa Cruz professor Soraya Murray goes beyond the technical discussions of games and instead offers a deep dive into their cultural dimensions.

An interdisciplinary scholar of visual culture, Murray is an associate professor of film and digital media who is also affiliated with the Digital Arts and New Media M.F.A. program–as well as the Art and Design: Games and Playable Media B.A. program–in the UC Santa Cruz Arts Division.

On Video Games critically examines blockbuster games such as The Last of Us, Metal Gear Solid, Spec Ops: The Line, Tomb Raider and Assassin’s Creed to show how they are profoundly intertwined with American ideological positions and current political, economic, and cultural conflicts.

In a world where profits from the gaming industry now surpass revenues from the film industry worldwide, Murray looks at how video games both reflect and provoke societal fears, hopes, and dreams, as well as complicated struggles for identity and recognition.

She also explores how video games are at the cutting-edge of power relations, helping to shape opinions and evoke emotion, much like film and music.

I recently spoke with Murray about On Video Games: The Visual Politics of Race, Gender and Space:

Q. What inspired you to write this book?

A. Video games are a massive global industry and highly influential forms of visual culture like film and television. Yet the public discourse around them is incredibly limited. Mostly, it consists of moral panics around whether video games make you violent, and they are thought of as beneath serious consideration. I have been startled by the degree to which scholars who are committed to visual studies have largely been neglecting games, despite their obvious reach and significance. As someone with in-depth training in visual studies, and who grew up playing games, I am well positioned to innovate ways of understanding video games as forms of “playable” visual culture.

Q. Can you give some examples of how blockbuster video games are deeply entangled with contemporary political, cultural, and economic conflicts?

A. When I say that games are “political” or “cultural”, I do not mean that games engage directly with the political process, or that they present themselves in the same mode as other cultural forms like art, music or theater. But they do create playable scenarios that may engage with political subject matter, and respond to political or cultural realities in a topical way—with varying degrees of responsibility. Games exist in social, cultural and political moments. They respond to their moment, presenting particular worldviews and value systems. In engaging with these games, we may adopt, contest or reject the visions they propose.

Q. Can you also give examples of how mainstream games both reflect and create larger societal fears, hopes, dreams, and struggles for recognition?

A. In my book, I talk about Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, which is partially set in 1980s Soviet-controlled Afghanistan. It struck me as no accident that the “background” of this hyper-macho military-themed action-adventure game was the very site where the Taliban came into being—and eventually al-Qaeda. It taps into notions of the “war on terror” and the “axis of evil” in ways that prick the player, even if they are not specifically aware of how the game is working on them.

More recently, there have been some pointed discussions about the use of political content in mainstream games like Detroit: Become Human (which invokes race-based social justice via androids), Far Cry 5 (which indirectly deals with Brexit and the 2014 Bundy standoff) and the forthcoming Tom Clancy’s The Division 2 (set in Washington D.C. and featuring themes of saving the US from tyranny). One of the major contributions of my book is a chapter that ultimately forecasted the rise of the alt-right in its struggle toward recognition, by analyzing the turn toward representations of victimized or disadvantaged white male protagonists in the Obama era and after.

Q. How are games at the frontline of power relations? And how might we deal with this?

A. Video games can shape hearts and minds the same way that music and cinema can respond to politics and capture a certain feeling, stoking fervor or invoking protest. Games can be incredibly persuasive rhetorical devices. In the same way that political ignorance is an impediment for democracy to function well, the lack of a mature critical studies apparatus allows a lot of shabby ideas to fester in video games under the guise that games are an apolitical place for “fun”.

The more we understand that, as play scholar Miguel Sicart says, games are ethical objects and players are ethical agents, the better we will become at creating a critical studies of games that can struggle with the medium in a constructive way. One of the unique aspects of UCSC’s games program is its commitment to these ideas.

Q. What is the most important thing you hope that people learn from this book?

A. For other games scholars interested in talking about games from a visual studies or cultural studies perspective, this book can be useful for understanding the stakes involved, the necessity for such analyses, and model some possible examples.

For everyone else, realize that video games are global mass culture, far larger than television and film and the music industry, and yet video games have been operating with comparatively little of the critical apparatus these other forms have. Video games are machines for thinking. I want people to be aware of this and have the tools to decide for themselves what kinds of thinking machines they want to play with, rather than the opposite scenario, where the games are simply working on them.