Nearly half the Earth’s highly threatened vertebrates occur on islands, according to a new study, which also found that effective management of invasive species could benefit 95 percent of the 1,189 threatened island species identified.

The foundation of the paper, published October 25 in Science Advances, is a database mapping the global distribution of highly threatened vertebrates and invasive species on islands. The Threatened Island Biodiversity Database lays the fundamental groundwork for planning conservation actions to prevent extinctions.

The first database of its kind, it is the culmination of an intensive systematic review of over 1,000 available datasets, publications, and reports, as well as consultation with more than 500 experts worldwide with specialized knowledge about native and invasive species on islands. From this investigation, researchers identified and mapped all 1,189 land-based amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals breeding on 1,288 islands and listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Investigators then documented whether introduced, damaging (invasive) vertebrates, such as rats and cats, occurred on the same islands. The dataset also contains important social, political, and ecological information about each island, critical for informing conservation decision-making.

“The opportunities to prevent extinctions are now laid out right in front of us,” said lead author Dena Spatz. “This knowledge base of threatened island biodiversity can really empower more efficient and better-informed conservation planning efforts, which is exactly what our planet needs right now.”

Spatz, now a conservation biologist at Island Conservation, began this work as a graduate student at the UC Santa Cruz Coastal and Conservation Action Laboratory (CCAL) led by coauthors Donald Croll and Bernie Tershy (who also founded Island Conservation). CCAL, Island Conservation, BirdLife International, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (SSC) Invasive Species Specialist Group created the Threatened Island Biodiversity Database to guide conservation planning and prevent island extinctions.

Why Islands?

Islands are isolated landmasses surrounded by ocean that hold many of the most threatened species in the world. For example, the Floreana mockingbird in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador, disappeared from its namesake island in the 19th century, mere decades after human colonization. The mockingbird was wiped out primarily by invasive species on the island, including rodents and feral cats which remain on Floreana and prevent the mockingbird's safe return. The few hundred individuals left of this critically endangered bird are now confined to tiny predator-free islets adjacent to Floreana.

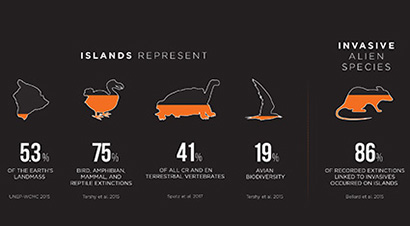

Unfortunately, this is a common story for island wildlife, which suffer disproportionately from endangerment and extinction as compared with plants and animals on continental land-masses. In part, this is because animals on islands tend to lack defenses against mainland species often introduced, intentionally or unintentionally, by humans. Islands represent only 5.3 percent of the world’s land area, yet have hosted 61 percent of all recorded extinctions since 1500. The majority of those extinctions were driven by invasive species, particularly rodents and cats, responsible at least in part for 44 percent of bird, mammal, and reptile extinctions in recent centuries.

Spatz and colleagues created the Threatened Island Biodiversity Database as a foundational tool to pinpoint which species to protect, and where, to prevent extinctions.

Hope on islands

On some islands, it is feasible to implement biosecurity measures to prevent invasive species from arriving and becoming a threat. And for many islands with invasive species, it is possible to completely remove the interlopers, which has led to remarkable recovery stories for native species around the world. On Anacapa Island in the Channel Islands, California, for example, the successful removal of invasive rats led to positive outcomes for the vulnerable Scripps’s murrelet and the recent discovery of the endangered ashy storm-petrel.

Coauthor Stuart Butchart, chief scientist at Birdlife International, said “The datasets assembled for this paper support the most comprehensive assessment yet of the distribution of threatened species on islands and where they occur with invasive alien vertebrates. The analysis underpins ongoing efforts to determine on which islands preventing invasions and controlling or eradicating invasive species would provide the greatest contribution to global biodiversity conservation.”

While the species threatened by invasive vertebrates make up almost half of all highly threatened land vertebrates world-wide, they occur on a fraction of the Earth’s landmass and on fewer than 1 percent of the world’s islands. Many of these islands were found to be relatively small and with minimal human habitation, especially those with threatened reptiles and birds. These islands represent a significant opportunity to address the biodiversity crisis.

“The database validates the importance of islands globally for biodiversity conservation and lays the groundwork for pinpointing efficient and effective conservation action at global and regional scales,” said coauthor Piero Genovesi, head of Wildlife Service - ISPRA Institute for Environmental Protection and Research and Chair of the IUCN SCC Invasive Species Specialist Group.

The paper highlights a handful of these islands where conservation efforts would be important. For example, Gough Island, a U.K. Overseas Territory of the St. Helena and Tristan da Cunha island group in the Atlantic Ocean, is home to six species that are highly threatened, such as the Tristan albatross. Invasive mice occur on the island as well, threatening the survival of the albatross and other threatened species.

“The global nature of the paper offers a comparative look at threats to biodiversity and conservation opportunities,” Spatz said. “Furthermore, it provides national and regional governments and NGOs with critical biodiversity information assembled on a global platform, which can inform and stimulate promotion, fundraising, and action to protect species from extinction.”

Next steps, she said, are to apply the information gathered from this dataset to key conservation planning efforts at global and regional scales, combining other factors affecting the feasibility of implementing island conservation interventions to identify the most important islands where conservationists should focus global efforts to prevent extinctions.