Arts & Culture

Murals tell a story of pan-Latino solidarity in SF’s Mission District

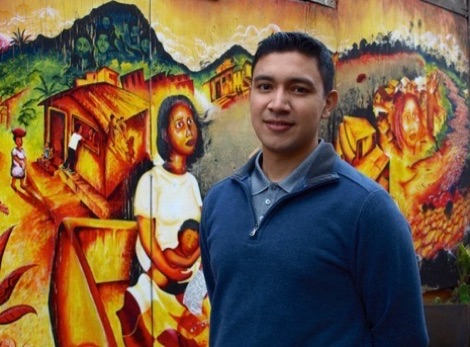

Graduate student Mauricio Ramírez is an artist, a muralist, and a native San Franciscan who is fascinated by the murals in the Mission District of San Francisco—and by the progressive coalition of artists and immigrants that coalesced during the decades they were painted.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

The Mission District in San Francisco boasts good weather, great food, and more murals than any other neighborhood in the city.

Many of these paintings celebrate the landscapes and cultures of Central America, as well as the violence and civil wars that racked Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Those conflicts fueled the migration of thousands of Central Americans to San Francisco over three decades, beginning in the 1980s.

Mauricio Ramírez is an artist, a muralist, and a native San Franciscan who is fascinated by the Mission’s murals—and by the progressive coalition of artists and immigrants that coalesced during those decades.

“I saw these murals created mostly by Mexican Americans and Chicano artists, and I wondered what would make them paint in solidarity with Central Americans,” explained Ramírez, a third-year doctoral student in Latin American and Latino studies whose dissertation focuses on transnational solidarity in Latinx visual art in the San Francisco Bay Area. “Mexican American and Chicano activists were very welcoming.”

Rooted in the Chicano rights movement

Scholars have written about the city’s support for Central American refugees, the sanctuary movement, and opposition to U.S. intervention in the region, but little about the art that blossomed during the era.

“A lot of the Mexican American artists came from the Chicano rights movement of the 1960s, and theywere against the Vietnam War,” said Ramírez. “A lot were self-taught. They were politically motivated, and one of their outlets was art.

“For newly arrived Central Americans, seeing images from their homelands provided a warm welcome. “They could feel at home, they could feel safer,” he said.

Ramírez earned his B.A. in art from UC Santa Cruz (Oakes, 2012) before getting a M.A. in teaching visual arts from the University of the Arts in Philadelphia in 2014. He puts his art and teaching talents to work every Friday night, teaching art at juvenile hall in San Mateo and San Francisco.

“It’s one way of giving back,” said Ramírez, who became immersed in the Mission’s mural scene as a high school student. He contributed to murals all over the city as a youth.

With support from the Social Science Research Council Dissertation Proposal Development program, Ramírez spent the summer interviewing muralists, conducting library research, and combing archives to recreate the story of the Mission’s murals, particularly those adorning the walls and garage doors of Balmy Alley, a one-block street between 24th Street and 25th Street that is home to the most concentrated collection of murals in the city. Balmy Alley’s murals appeared in large numbers in response to a 1984 Artist Call to protest U.S. intervention in Central America; a group of 36 artists created 27 murals in Balmy Alley during the summer of 1985, helping to establish the Mission as a “mural environment.”

Three murals

The mural “Culture Contains the Seed of Resistance,” painted by Miranda Bergman and O’Brien Thiele. (Photo by Mauricio Ramírez.)

One of the alley’s murals, “Culture Contains the Seed of Resistance” painted by Miranda Bergman and O’Brien Thiele, speaks to state-sanctioned violence in Central America. The left panel depicts elders holding black-and-white portraits of victims, “the disappeared,” while a youth paints “Resiste” on the wall. On the right side of the mural, smiling campesinos and musicians are pictured with an overflowing cornucopia of tropical fruits, a rainbow river flows in the foreground against a backdrop of agricultural fields, mountains, and sky.

In a 1990 mural titled “Ceasefire” by Juana Alicia, a youth stands proudly against a backdrop of fields and mountains, while the foreground is dominated by the image of two hands raised in resistance, guns pressing into the palms.

“Missionmakeover,” by Tirso Araiza and Lucia Ippolito.

A more recent two-panel mural, titled “Missionmakeover” by Tirso Araiza and Lucia Ippolito, is a study in contrasts: On the left, a police officer is handcuffing a young Latino, with a low-rider, a pitbull, and a bus featured prominently; on the right, a bustling 24th Street streetscape is crowded with pedestrians, cyclists, neighbors, and lavishly painted Victorian homes. In the foreground, a uniformed police officer chats with a blonde-haired woman wearing high heels, Starbucks cups in hand and dogs at their feet.

Gentrification

For Ramírez, the pace of gentrification has added to the urgency of his project.

“Most of the murals were created by Latinos, and Latinos are being displaced,” he said. “What’s going to happen to these murals down the line? Will they be protected? Conserved? Whitewashed?”

Ramírez is interviewing well-known Bay Area artists, such as Ray Patlan and Patricia Rodriguez, as well as leaders of community organizations such as Precita Eyes Muralists Association, a nonprofit that has helped create more than 400 murals throughout San Francisco and is active in preserving existing artwork.

“When people think about murals, they don’t think about high art, but some of these murals are impressive works by really talented artists,” said Ramírez.

Ramírez is one of twelve UC Santa Cruz graduate students who received support from the campus’s new Social Science Research Council Dissertation Proposal Development program. Recipients received $5,000 and were invited to attend two dissertation-proposal workshops with doctoral students and their faculty advisers from four other universities. As the lead administrator for the UCSC program, which is hosted by the Institute for Humanities Research and the Graduate Division, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Tyrus Miller attended the June workshop in Pittsburgh.