Campus News

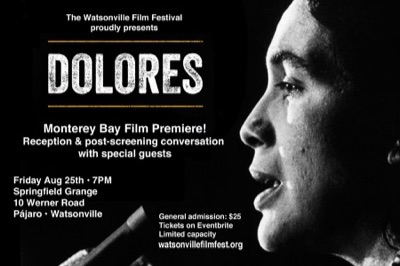

Alum and independent filmmaker Peter Bratt directs, writes, and produces documentary about labor activist Dolores Huerta

Independent filmmaker Peter Bratt, a 1986 politics graduate of Cowell College, has written, directed, and produced a new documentary about legendary labor activist Dolores Huerta.

Coachella, CA: 1969. United Farm Workers Coachella March, Spring 1969. UFW leader, Dolores Huerta, organizing marchers on 2nd day of March Coachella. © 1976 George Ballis/Take Stock / The Image Works NOTE: The copyright notice must include "The Image Works" DO NOT SHORTEN THE NAME OF THE COMPANY

Coming from a feature film background, Bratt had never made a documentary. But he immediately recognized the opportunity to rewrite a chapter of American history that had overlooked Huerta, the co-founder with Cesar Chavez of the first farm workers unions.

And so Bratt said yes. On September 1, his film, Dolores, opens in theaters in New York, Los Angeles, Seattle and San Francisco Bay Area. Already the recipient of numerous accolades and awards, including the Audience Award for Best Documentary Feature at the San Francisco Film Festival, Dolores does justice to a woman who has dedicated most of her 87 years to fighting for social justice. The film received a 20-minute standing ovation at its Sundance Film Festival premiere.

Which doesn’t mean Huerta liked being the center of attention during the making of the film.

“Dolores kicked my butt a few times during the process,” Bratt recalled during a recent interview. “Like a lot of activists, she didn’t want the focus to be on her—she wanted it to be about organizing and movement building.”

Bratt, however, was determined to capture the personal story of the woman, as well as the impact of her work. “It was really difficult for her, particularly in the interview process—which sometimes made it difficult for me,” he said. “Watching the first cut with her was a tough experience, because she’s in every frame.”

Huerta’s children impressed upon her the value of her story as an inspiration to others. “They repeatedly told her young Latinas need to see and know her story, that her story could inspire people to action. Once she understood that, she got completely on board,” said Bratt. “She’s going out (on tour) with the film, using it as an organizing tool, and it is inspiring people to action. As my brother Carlos Santana likes to say, ‘Dolores is a force of nature.’”

That ferocity has fueled Huerta’s fight for racial and labor justice for more than 60 years. Huerta was a chief strategist of the grassroots organizing, boycotts, lobbying, and campaigning that won rights for farm workers in the 1960s and ’70s, and she was an outspoken feminist, on the front lines of struggles for women’s rights, as well. She was also the mother of 11 children and a deeply private person.

“People don’t know she’s a jazz aficionado and an incredible dancer who trained professionally,” said Bratt. “She would work 16 hours and then dance the night away. She still does—she’ll dance until two or three o’clock in the morning, and on many occasions during production, she would wear out my crew.”

Music and dance became the thematic motif of the film. “That was my way into the film artistically,” said Bratt. “I wanted the film to have that movement and musicality—like Dolores herself.”

Bratt’s team reviewed seven decades worth of footage. “The process of making a documentary is terrifying,” said Bratt, who comes from a background of narrative filmmaking. “You’re taking a leap of faith, hoping you’ll discover the narrative and visual motif during the process.”

Eighteen months into the filmmaking, archival producer Jennifer Petrucelli discovered 16-millimeter footage of an hour-long interview with Huerta and Chavez that became the narrative theme of Dolores.

“I’ve fallen in love with the documentary medium,” said Bratt. “Filmmakers have to be cross trainers these days to stay working. There are challenges to each genre, but I find documentaries to be one of the most exciting. And this one took everything.”

It was at UC Santa Cruz that Bratt first entertained the idea of making films. “I took a film class my junior year,” he recalled. “I thought it would be a chill, kickback class and we’d get to watch movies all spring.”

Instead, he found himself writing a paper a week and analyzing the American musical from a Marxist-feminist perspective. “A light went on for me, writing those critical papers,” he said. “I started thinking about how film and television shape our perceptions of the world, and I became interested in training that critical lens on race.”

Film provides a platform for asking questions about who holds power and who controls the collective narrative in society, he said. “That’s all Santa Cruz—the critical thinking that comes with a liberal arts education,” said Bratt, who remembers having animated discussions with his housemates, and attending dinners at professors’ houses. “It was such an exiting time,” he said.

Bratt won a Chancellor’s Award for his paper about the American musical, and his professor, Vivian Sobchack, encouraged him to think about making films. “Her recommendation got me into NYU’s graduate film program,” he said.

Bratt’s previous films include La Mission, a 2009 drama about family and masculinity set in the Mission District of San Francisco where Bratt grew up. When Santana approached him more than four years ago about making a film about Huerta, Bratt said it felt like a “cultural directive” from one storyteller to another to fulfill a “historical obligation.” The weight of responsibility was eased by excitement about the prospect of presenting a fleshed out version of an iconic figure. Likening Huerta to other champions of the international struggle for social justice—Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, and Chavez—Bratt said he wanted to make a film that captured the complexity of this iconic woman.

“When we look back, we sometimes sanitize and homogenize a little bit,” said Bratt. “It’s natural. We do it with our heroes, those we respect and admire. Does Dolores, the human being, have any regrets? Of course she does. I wanted to explore what those regrets and mistakes were, and how they might inform who she is today. She had 11 children, and so her story is also a story about familia, family.”

When Bratt and executive producer Santana launched the project in 2014, no one foresaw the relevance the film would have in 2017.

Dolores received its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival on the afternoon of January 20—the day Donald Trump was inaugurated. “The theater almost became like a church,” recalled Bratt, speaking two days after white supremacists created mayhem in Charlottesville. “It’s amazing to me how relevant and urgent her story is today.”

Ever the activist, Huerta is using the film as an organizing tool. “During the Q&A after screenings, she’ll get people cheering and chanting, telling the audience to register to vote, to go back to their community and organize,” said Bratt. “It’s great to march, she says, but it’s not enough. You have to organize in your community.”

“As a person who wants to inspire social change, I’ve learned a lot from her. In many ways, she’s been a teacher for me.”