Campus News

Ripples in cosmic web measured using rare double quasars

Astronomers have made the first measurements of small-scale ripples in the primeval hydrogen gas left over from the Big Bang.

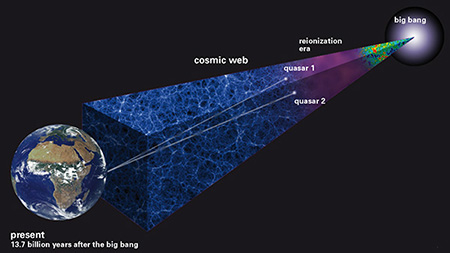

The most barren regions of the universe are the far-flung corners of intergalactic space. In these vast expanses between the galaxies, a diffuse haze of hydrogen gas left over from the Big Bang is spread so thin there’s only one atom per cubic meter. On the largest scales, this diffuse material is arranged in a vast network of filamentary structures known as the “cosmic web,” its tangled strands spanning billions of light years and accounting for the majority of atoms in the Universe.

Now a team of astronomers including J. Xavier Prochaska, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz, has made the first measurements of small-scale ripples in this primeval hydrogen gas. Although the regions of cosmic web they studied lie nearly 11 billion light years away, they were able to measure variations in its structure on scales a 100,000 times smaller, comparable to the size of a single galaxy. The researchers presented their findings in a paper published April 27 in Science.

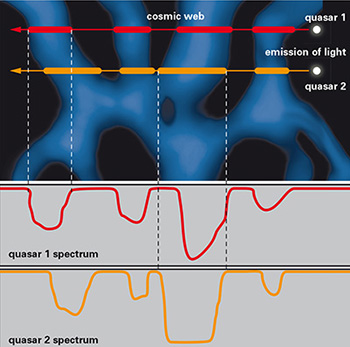

Intergalactic gas is so tenuous that it emits no light of its own. Instead astronomers study it indirectly, by observing how it selectively absorbs the light coming from faraway sources known as quasars. Quasars constitute a brief hyper-luminous phase of the galactic life-cycle, powered by the infall of matter onto a galaxy’s central supermassive black hole. They thus act like cosmic lighthouses—bright, distant beacons that allow astronomers to study intergalactic atoms residing between the quasars location and Earth.

Because these hyper-luminous episodes last only a tiny fraction of a galaxy’s lifetime, quasars are correspondingly rare on the sky, and are typically separated by hundreds of millions of light years from each other. In order to probe the cosmic web on much smaller scales, the astronomers exploited a fortuitous cosmic coincidence: they identified exceedingly rare pairs of quasars, right next to each other on the sky, and measured subtle differences in the absorption of intergalactic atoms measured along the two sightlines.

“One of the biggest challenges was developing the mathematical and statistical tools to quantify the tiny differences we measure in this new kind of data,” said Alberto Rorai, a post-doctoral researcher at Cambridge university and lead author of the study. Rorai developed these tools as part of the research for his doctoral degree, and applied his tools to spectra of quasars obtained by the team on the largest telescopes in the world, including the 10-meter Keck telescopes at the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

The astronomers compared their measurements to supercomputer models that simulate the formation of cosmic structures from the Big Bang to the present.

“The input to our simulations are the laws of physics and the output is an artificial universe which can be directly compared to astronomical data. I was delighted to see that these new measurements agree with the well-established paradigm for how cosmic structures form,” said Jose Oñorbe, a post-doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, who led the supercomputer simulation effort. On a single laptop, these complex calculations would have required almost a thousand years to complete, but modern supercomputers enabled the researchers to carry them out in just a few weeks.

“One reason why these small-scale fluctuations are so interesting is that they encode information about the temperature of gas in the cosmic web just a few billion years after the Big Bang,” said Joseph Hennawi, a professor of physics at UC Santa Barbara who led the search for quasar pairs.

Astronomers believe that the matter in the universe went through phase transitions billions of years ago, which dramatically changed its temperature. These phase transitions, known as cosmic reionization, occurred when the collective ultraviolet glow of all stars and quasars in the universe became intense enough to strip electrons off of the atoms in intergalactic space. How and when reionization occurred is one of the biggest open questions in the field of cosmology, and these new measurements provide important clues that will help narrate this chapter of the history of the universe.