Campus News

Structure of human astrovirus could lead to antiviral therapies, vaccines

Research led by structural biologist Rebecca DuBois is laying the foundation for new antiviral therapies and vaccines for human astroviruses.

Human astroviruses infect nearly everyone during childhood, causing diarrhea, vomiting, and fever. For most people, it’s not a serious disease, but structural biologist Rebecca DuBois saw how devastating it can be when she worked at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“There were all these young cancer patients who were successfully fighting their cancer, but they were getting severe chronic astrovirus infections because the chemotherapy suppressed their immune systems, and there was no treatment for it,” said DuBois, now an assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

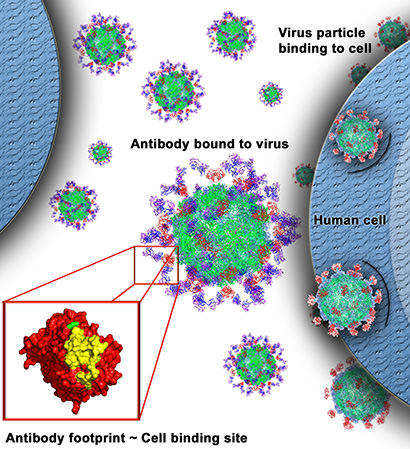

By studying the astrovirus capsid, the protein shell of the viral particles, the DuBois lab is laying the foundation for new antiviral therapies and vaccines for human astroviruses. In a new study accepted for publication in the Journal of Virology, she used x-ray crystallography to show how a specific protein structure on the surface of the virus is blocked by a neutralizing antibody, thus preventing the virus from infecting human cells.

“We’ve identified a site of vulnerability on the surface of the virus that we can now target for development of a vaccine or antiviral therapy,” DuBois said. “These are the first results showing how a neutralizing antibody blocks this virus.”

Antibody binding site

The study shows how the antibody binds to a structure known as the astrovirus capsid spike domain, which projects from the surface of the virus. By binding to the spike domain, the antibody blocks the virus’s ability to attach to and infect human cells.

The new findings provide a roadmap for researchers to design a vaccine based on the spike domain that can induce neutralizing antibodies and prevent infection in children. The study also highlights the potential to develop therapeutic antibodies to treat severe astrovirus infections.

“Antibody therapeutics is a rapidly growing field. Many immunotherapies are being developed to target cancer cells, and we expect to see a growing number of antibody therapies for infectious diseases over the next ten years,” DuBois said.

Graduate student Walter Bogdanoff is first author of the paper. DuBois noted that the first three authors of the paper–Bogdanoff and undergraduates Jocelyn Campos and Edmundo Perez–have all been supported by the STEM Diversity Programs at UC Santa Cruz.

“It’s a great program that funds undergraduates and graduate students from diverse backgrounds to do laboratory research, and they really do become accomplished scientists and well prepared for graduate school and careers in science,” she said.

The other coauthors are research associate Yu Lin and project scientist David Alexander. This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by the Hellman Fellows Fund.