Campus News

Community gathers to strengthen public dialogue about Santa Cruz’s housing crises

New research by UC Santa Cruz sociology professors Miriam Greenberg and Steve McKay highlights housing issues

Across Santa Cruz, housing is an urgent and pressing problem. It is one of the most unaffordable cities in in the country because of escalating housing costs and stagnant wages.

“Housing affects everyone, but it does not affect everyone equally,” said sociology professor Steve McKay at a public presentation he led about housing problems in Santa Cruz county on Oct. 13.

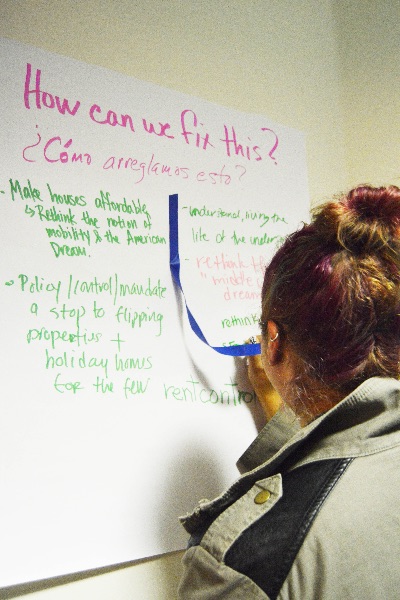

More than 400 community members packed the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History to hear preliminary findings from a housing study McKay is conducting with Miriam Greenberg, also a professor in sociology.

The event also kicked off Affordable Housing Week, a series of events to highlight and help people impacted by a lack of affordable housing in the area.

The study, titled No Place Like Home, sets out to address crucial questions surrounding housing, especially for renters. What does it mean to feel “at home” during an affordable housing crisis? What are the sacrifices of high rents?

Greenberg and McKay’s initial discoveries are devastating. Overcrowding, exorbitant rent burden, evictions, and fear of retaliation are some of the results that can be accessed on the project’s bilingual multimedia website.

Census of the invisible: researching the under-researched

Phase one of the project focused on Beach Flats, Lower Ocean, and Lower Pacific/ Laurel Streets, areas known for higher-than-average crime rates, dense urbanization, and poverty. This population is also difficult to reach, said McKay. For various reasons, residents may not respond to telephone and census surveys.

In many cases, they may not get asked at all and therefore remain uncounted, McKay added. Greenberg, McKay, and more than 50 student researchers surveyed 435 residents to create was McKay calls a “census of the invisible.”

To connect community with their research, students spent time getting to know local residents, who are predominantly Hispanic and Latino. The students helped with neighborhood cleanups, organized a health fair, and even hosted a kids movie night. These efforts helped build trust and rapport with survey participants. Meaningful relationships were built, which meant meaningful data could be collected.

“You need the community engaged to get the real numbers,” said sociology student Alma Villa.

More than numbers

Of the 435 survey respondents, 51 percent were Latino, 57 percent earned less than $30,000, 45 percent experienced a forced move in the last five years, and 32 percent reported overcrowding, defined as having more than two persons per bedroom.

73 percent of survey respondents experienced rent burden, defined by the American Community Survey as spending more than 30 percent of one’s gross income on rent and utilities.

But for 27 percent, more than 70 percent of wages go towards their housing. 80 percent of respondents who are rent burdened are Latino.

“It is not just graphs and numbers but lives of human beings and real people in your community,” said sociology major Celeste Covarrubias-Marcias, who described the cramped living conditions she witnessed. She reported seeing makeshift beds in kitchens, cramped units, and parents worried about their children’s well-being.

63 percent reported dealing with major problems such as fears of neighborhood safety, rowdy neighbors, and poorly maintained buildings. Sociology student Katie Marlow saw homes infested with rodents, cockroaches, and bedbugs.

“Home is not just shelter,” Covarrubias-Marcias emphasized. “It is comfort, belonging, and feeling safe.”

Housing as an environmental concern

The problem of housing is also a social and ecological problem, said Greenberg.

“Lack of affordable housing is a sustainability issue,” she said.

Greenberg pointed to the environmental cost of urban sprawl. As the lack of affordable housing pushes residents out, environmental problems are brought in. More people commuting means more cars on roads and more greenhouse gas emissions. More paved roads on the urban fringe is also of broader ecological concern, as asphalt prevents the natural seepage of rainwater, thus reducing our groundwater, and also fragments wildlife habitat.

Yet when sustainability is introduced into development plans, it tends not to include affordability resulting in contradictory effects.

While urban sustainability efforts have helped transform areas like San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and Santa Cruz into greener and more environmentally-friendly places, it has also made them more desirable and the kicker: more expensive. Poor and low income residents are pushed out again.

To address “green displacement,” social equity needs to be a central part of the discussion. Sustainability without affordability is not sustainable, Greenberg said.

Next steps

Phase two of No Place Like Home begins in January. Greenberg and McKay will focus on Live Oak. Phase 3 will start in April 2017 in Watsonville.

Santa Cruz residents are also encouraged to share their story on the project’s website.

The study is the latest in ongoing research funded by the UC Humanities Research Initiative and is an extension of Working for Dignity conducted by the Center for Labor Studies, the Critical Sustainabilities Project, and the Chicano Latino Research Center.