Campus News

Philanthropy in pursuit of a healthier planet

Alec and Claudia Webster, who help steward the philanthropy of the Helen and Will Webster Foundation, look at how they can accomplish the most good with their gifts.

The ideas come fast and early in the Webster house. How to use philanthropy to create a healthier planet? How to create change, leverage it, inspire it? How to turn an oil tanker?

“Welcome to our morning coffee: We sit around going, what about this, wouldn’t it be cool if …” says Claudia Webster.

Alec and Claudia help steward the philanthropy of the Helen and Will Webster Foundation, created by Alec Webster’s parents. In figuring out how to do the most good they can with the dollars available, they look at many opportunities and possibilities. The more they have learned and observed, the more clear their focus has become on UC Santa Cruz and its environmental programs.

“We feel like we’ve found this really special place in the universe. And this is what we want to do to bring attention to it, to strengthen it,” they say. In recognition of the Webster family’s commitment and support, the foundation is being honored in October with the 2016 Fiat Lux Award from the UC Santa Cruz Foundation.

Their most recent investment: endowing College Eight and naming it in honor of Rachel Carson, whose book Silent Spring in the 1960s kick-started the modern environmental movement. Their decision was both pragmatic and symbolic. The money will support environmental programs, and the name will telegraph a larger message about UC Santa Cruz and its values. It will introduce Carson to new generations and remind earlier ones of her critical role in awakening public interest in the environment—including halting the unchecked use of pesticides and herbicides.

When the Websters first began considering an endowment for College Eight—Alec is an alumnus—someone suggested they could name it Webster College. “The person who suggested that did not know the Webster family,” says Alec. “That is not what we are about.” This year, when they again turned their attention to College Eight, it was college Provost Ronnie Lipschutz who presented the idea of naming it for Rachel Carson. Immediately, they knew it was right.

The Websters learned the power of symbolism from an earlier campus project—the falling down Hay Barn at the entrance to campus. In proposing to rebuild the historic barn, they encountered skeptics and physical and bureaucratic hurdles. Today, the rebuilt barn is a popular and vibrant home for environmental programs and community activities. And it is a landmark that symbolizes the university’s powerful connection to the land, and of a future built on a history.

Growing into environmental activists

Neither Alec nor Claudia started out as environmental activists—they grew into it. They met in the ’70s in a geology class at UC Santa Barbara. (A class taught by Robert Norris, brother of Ken Norris, professor of natural history at UC Santa Cruz and marine mammal expert whose legacy includes founding the UC Natural Reserve System.)

Alec and Claudia dated, but their life together didn’t really start then. It would be 30 years later, after separate life experiences and being married to others, that they found each other again.

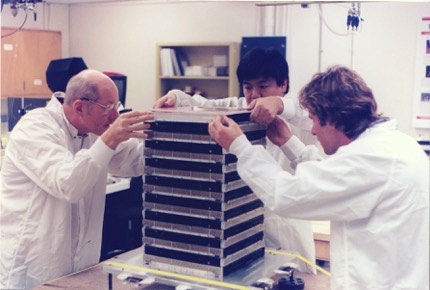

Alec had spent much of his career as a machinist helping design and build scientific instruments—for 14 years at the UC Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics. He helped build an instrument that studied collisions of electrons and anti-electrons for the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. And he was on the team that designed and prototyped the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. It’s still orbiting, still taking data on gamma rays from cosmic sources.

The down-to-earth side of Alec became increasingly intrigued by the environment—by soil, and plants, and how they all work together. His first taste of that had been as a kid when he and his older brother built an urban compost pit. Now he was on a campus where agroecology and soil science were taught. He talked professors into letting him take their classes—Margaret Fitzsimmons, Karen Holl, Steve Gleissman, and others—and then-chancellor MRC Greenwood into letting him enroll as a re-entry student. In 2002, he had his degree in Environmental Studies.

Claudia, meanwhile, had spent much of her career teaching art and raising her children in San Diego County. She worked with inner city kids who lived 25 minutes from the ocean but had never seen the ocean. Who had no idea where milk came from and were stumped when she put a sweet potato in a jar of water to sprout. “How did you get the things to come out of the sweet potato?” they asked.

When Alec and Claudia reconnected, they found they not only enjoyed the outdoors together, but shared a deep commitment to environmental and social justice. It is a core value they see at work at UC Santa Cruz—not just given lip service—and that has led to their support of multiple initiatives on campus. In addition to environmental programs, they have supported the University Library and the effort to reopen the Quarry Amphitheater.

They especially want students to experience the natural environment, from growing food on the campus farm to sleeping on the ground in the wilds of the Big Creek Reserve.

“Are we making any progress?” asks Claudia. “My experience in teaching has told me you never know, when you put good out into the world, do your very best, you never know whose life you’ll touch.” She remembers a former student telling her she had a huge impact on his life. It had nothing to do with art: “You smiled at me even after I called you an insulting name.”

Turning an oil tanker

The Websters liken efforts to create change to turning a tanker at sea. “We need to change the direction of the oil tanker,” says Alec. “We can only do it a little bit at a time, but eventually the tanker will be turned.”

Alec remembers standing on the shore as a boy with his dad—an engineer and inventor who pioneered life-saving cardiac catheters—as a huge tanker moved through the water. His dad told him the tanker was so big and heavy that even if there were something right in front of it, it would be unable to stop. He’s never forgotten that lesson.

“It takes thousands of people to create change. When you get into UC Santa Cruz, we’ve already picked 16,000 winners,” says Alec, who serves as a trustee of the UC Santa Cruz Foundation and will become its next chair. Among his goals: increasing support for research and the student experience as part of the Campaign for UC Santa Cruz. “It’s how to help boatloads of kids, not handfuls,” he says.

The Websters hope their support for UC Santa Cruz will inspire others to give—in time, talents, resources. “This is not a spectator sport,” says Alec. “It takes people at all levels to make good things happen. Everybody has something to give.”

Alec returns to the difficulty of creating meaningful change in the world. “How do you turn the oil tanker? At sea, it takes forever. In harbor, you put a tug boat on its bow, you go chh, chh, chh” he says. “And you push.”

The Campaign for UC Santa Cruz supports excellence across the university through increased private investment in the people and ideas shaping the future. It is bringing critical new resources to the student experience, excellence in research, and the campus commitment to environmental and social justice.