Scientists and global leaders are busy seeking solutions to climate change, but a growing number of experts in the field think that another group will have to play a critical role: entrepreneurs. And now is the time for entrepreneurs to enter the fray.

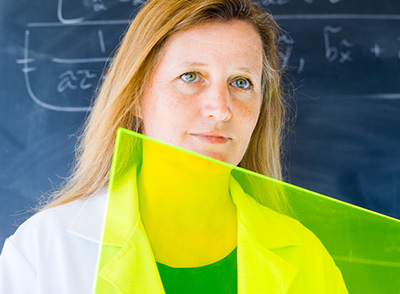

“It’s only been in the last five years that we’ve seen the real impacts of climate change on our livelihood, and that’s going to cause the right situation for entrepreneurs to play a role in climate change mitigation,” said UC Santa Cruz physics professor and tech entrepreneur Sue Carter.

The impact of climate change couldn’t be more real to Carter. In 2015, her house burned to the ground in California’s massive Butte fire, during the worst wildfire year on record in the western U.S.

“It was so hot that even the wood burning stove was completely melted,” said Carter.

When climate change is a vague, distant concept, it’s easy to ignore. When your house burns to the ground, you pay attention. But where others might have just seen tragedy, as both a researcher and entrepreneur, Carter saw opportunity.

Climate entrepreneurship gets hot

Multiple factors are coming together at the same time, according to Carter. In addition to the increased visibility of climate change’s effects, there is a culture shift led by the current generation of students, record-low prices for clean energy that are becoming competitive with fossil fuels, and increasingly favorable policy changes.

Policies have proven to be effective to change behavior, and can provide opportunities for clean tech businesses to gain a competitive advantage. Soliculture, Carter’s own startup that sells solar greenhouse technology originally developed in her UC Santa Cruz lab, has benefited from the tax rebates available to consumers who invest in solar building projects.

Even the increasing rate of natural disasters has a silver lining for Carter. Disasters can free up money for quick action, sidestep political hurdles, increase a problem's visibility and provide an opportunity to rebuild in a sustainable way.

“You can use the huge influx of cash from natural disasters to cause change to happen on a much faster timescale than is normally possible,” said Carter. “If you’re going to rebuild a home with insurance money, you can now build back your home in a completely net-zero way. In fact, you can even generate extra electricity, so it’s better than net-zero.”

Time is of the essence

Time to market is a challenge for all entrepreneurs, doubly so for those in the clean energy and climate change space. Conventional wisdom is that it takes 20 years to advance from invention to market for a brand-new technology, but climate change isn’t waiting.

“A 20-year delay is equivalent to about a one-degree Celsius rise and a one-meter rise in sea level,” said Carter.

To Ilan Gur, founding director of Cyclotron Road, an energy technology incubator at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, speed is where research university-based technology incubators can play a critical role.

“Very early-stage tech startups might spend the first few years in research and development. Why not do it within a research university lab environment? The facilities are already there – it allows you to get started quickly, without wasted money, and to pivot as needed,” said Gur.

“For hard tech, physical-science-based startups, the biggest issue right now is that no investors are interested in funding companies at the earliest stage,” said Gur. “The timescale is too long and too risky for most investors. But that means it can be nearly impossible for innovators to get started.”

Cyclotron Road is trying to bridge this funding gap, providing early-stage funding for promising energy tech entrepreneurs that get accepted into the incubator, combined with access to the facilities and expertise at Berkeley Lab. The current group of incubating innovators includes Marcus Lehmann, founder of CalWave, a startup with a novel approach to harnessing the power of the ocean to create clean electricity, and the founders of Spark Thermionics, who are developing microfabricated devices that convert wasted heat into electricity.

Thanks to growing entrepreneurship programs within universities and a generation of students that is highly aware of the impact climate change will have on their future, clean tech entrepreneurs are getting an early start.

The effect of these programs has been clear at the University of California. Over the past five years, nearly half of all startups to emerge from UC have been based on student inventions, a rapid acceleration – and many of these companies are in the clean tech space.

Getting traction

Sometimes the problem with new ideas is that they’re new.

“If an idea is sufficiently powerful that it matters, it will sound impossible,” said Gavin McCormick, co-founder and executive director of the clean tech startup WattTime. “It often comes down to one really well-done proof of concept.”

You need a proof of concept to get funding, but you need funding to make a proof of concept. Many great ideas get stuck here, before they can gain momentum.

McCormick was a graduate student at UC Berkeley when he and co-founder Anna Schneider came up with the concept for WattTime, a software tool that allows internet-connected devices to selectively draw power when the local grid has surplus clean power. The idea was exciting, but they needed funding to make it real.

They found an early group of supporters close to home: UC Berkeley undergraduates, who awarded them seed funding from the UC Berkeley Green Initiative Fund, which provides grants to support sustainability projects on campus.

“They were willing to take the risk,” said McCormick. “There’s a culture of trying at universities, and particularly among students, that can be really supportive of new ideas.”

After the initial round of funding, WattTime got a further push from the CITRIS Foundry at UC Berkeley, an applied tech incubator that supports early-stage startups and helps them develop and refine prototypes.

Catching the big ideas

University-based incubators can play another key role, according to McCormick: not letting new, potentially world-altering ideas slip through the cracks.

Gur concurs. “Right now, if there are 20 people graduating with a Ph.D. who could go on to change the world in energy, chances are there are 20 people scratching their heads wondering where to get started.”

McCormick might never have started WattTime had he not attended a campus hack-athon that opened his eyes to the possibility of founding an organization. It hadn’t occurred to him as a real prospect before.

“Most researchers aren’t looking to start a business – many don’t even know that they can,” said McCormick. “They’re often not even aware how valuable their ideas are. Someone has to give them that first nudge.”

McCormick thinks this nudge is essential if we’re to get the limited funding available to companies that can have the greatest effect on climate change.

“Not all energy technology helps climate change,” said McCormick. “There’s much more acceptance now that things can change, but along with that there’s also very little vetting of ideas.”

Crowdfunding, for example, has resulted in both notable successes and failures.

“The enthusiasm is good, but we need better systems for experts to be consulted on business ideas. With the right information, entrepreneurs can both do good and do well.”