Campus News

Enthusiasm, excitement for discovery drives Grad Slam winner

Planetary science student Michael Nayak has opened up new fields of study and planetary data analysis.

As a little boy growing up in Torrance, Calif., Michael Nayak would stare into the night sky and watch stars pass over his house.

While the “stars” turned out to be planes on their approach to Los Angeles International Airport, they nevertheless set off a longing in a kid who would grow up to become an Air Force captain, a pilot, a skydiving instructor, a co-principal investigator on a satellite mission, the author of a published paper about a strange moon named Phobos, and now a third-year grad student in Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz.

Earlier this month, Nayak won the $3,000 grand prize in UC Santa Cruz’s second annual Grad Slam competition. He will now go on to represent UC Santa Cruz at the UC-wide Grad Slam finals April 22 at LinkedIn headquarters in San Francisco.

“Seeing stars amidst the smog was always a treat,” says Nayak, 29, who goes by “Mikey”. “Over time that turned into something I really care about.”

Spend an hour with Nayak and you’ll walk away with stories about pilot emergencies, quivering skydiving students, hopping moons, gravitational modeling, and why we should figure out a way to live on Mars.

He’ll tell you about the excitement of leading a mission to launch a unique shoe-box-sized satellite into space. He’ll talk of joining the military because it afforded him the opportunity to do the kinds of things he wanted at a young age, including being named lead flight director for a project that involved a military reconnaissance satellite that was about to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. Nayak was 24 at the time.

“To put it in perspective,” he says, “flight directors for NASA missions are usually in their early 40s.”

It’s not bragging when Nayak says these things. Rather, they seem to come from a place of enthusiasm and excitement for discovery.

“When you’re a planetary scientist, you really learn about how little you know,” Nayak says at one point as he explains his research into a planetary system named Kepler-32 and his work on Mars’s mysterious moon called Phobos.

“What sets him apart as a researcher,” says his mentor and UC Santa Cruz Emeriti Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences Erik Asphaug, “is that he’s clamoring for good ideas to work on, and enthusiastic about what can be done to turn a hypothesis—that is, an eggheaded idea on a blackboard or on a paper napkin—into a substantial theory backed up by formidable sets of calculations.”

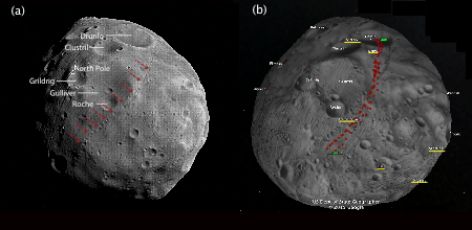

Take Mars’s moon, Phobos, for instance. For 40 years, scientists have wondered about the strange grooves on this lumpy, potato-shaped moon. Part of the explanation for the grooves was that they were stretch marks caused by the spiral pull of Mars, which is slowly sucking the moon back to itself. Not all of the channels fit that model, however.

Working with Asphaug, who is now part of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, Nayak was able to use gravitational modeling to show that some of the mysterious grooves were caused by debris from asteroid hits that rose up and, thanks to the tidal forces of the close-by Mars, fell back to the moon days or weeks later.

His discovery opened up a new field of study and of planetary data analysis.

“So what Mikey has done for Phobos, is basically to pound a peg into the sand around which we can anchor a lot of modern theories,” Asphaug says.

Nayak and Asphaug have submitted a proposal to NASA to look further into the nature of this unique moon.

Nayak, who is supported by a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship, is also interested in faraway planetary systems, including one called Kepler-32. That system contains five close-by planets whose gravities, like bullies in a schoolyard, are constantly fighting for dominance.

Nayak’s research showed not only that moons could exist in this system but also what they might look like, and the fact these moons could hop from one planet to another because of shifting regions of gravitational stability.

“These cramped systems are more common than our sparse solar system,” Nayak says of Kepler-32. “So if that’s the norm and we’re not, that’s what we really need to understand. Maybe that will give insights into why we’re different.”

The discussion of distant solar systems turns to Nayak’s hope that humans might, one day, be able to survive on Mars. His eyes light up as he talks.

“I think, in the future, we will find it really important to understand other worlds and therefore our limitations within them,” he says. “I think I’ll be an old man before then, but it would be super cool to sit back and say: ‘Back in my day I helped make that happen.’”