Campus News

The figure as an anatomical event

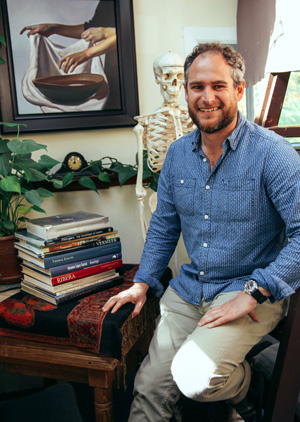

Art instructor Noah Buchanan is bringing the exacting study of anatomy and classic technique into the 21st century.

The pencil in Noah Buchanan’s hand swoops across the paper, leaving lines and angles that, over the next few seconds, begin to turn into the perfect rendering of a human skull.

“I call it architectonic drawing,” Buchanan explains as he sketches in the warm light of the converted North Coast farm shed that houses his studio. “It’s the idea of observing a subject matter that is fully organic but drawing it in a way that conveys its underlying geometric structure. I’m superimposing a planar logic upon the organic form.”

If Buchanan, 39, sounds more like a scientist than an artist, it’s no accident. The UC Santa Cruz lecturer and alumnus (Porter ’00) is a disciple of classical art, a man who is bringing the exacting study of anatomy and classic technique into the 21st century and exposing scores of UC Santa Cruz students who have taken his popular figure drawing and painting classes over the past eight years.

Says Buchanan simply, “I’ve always gravitated toward things that are technically complicated. Classical drawing and training involve levels of technical complication that intrigue me.”

Buchanan grew up in Southern California, the only child of a single mom who was a writer. According to his mother, she put art books into his crib when he was an infant, so it probably wasn’t much of a surprise when, in fourth grade, Buchanan began making lifelike drawings of his own hand. Or that, when he went to the movies, he’d watch the way shadow and light played across the actors’ faces instead of following the plot.

But it was at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts that Buchanan was pulled, almost obsessively, into the study of human anatomy. Even after his assignments were done, he says, he’d spend hours copying diagrams from Robert Beverly Hale and Dr. Paul Richer’s Artistic Anatomy book and quizzing himself on the names of bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

“My intention is to depict the figure as an anatomical event that houses the spirit of the human condition,” Buchanan says. “There are so many poetic notions associated with the heart and lungs, and the idea that these vital elements are carried along inside the vessel of the human figure as we search, struggle, fail, and succeed is a beautiful idea to me.”

As he talks, his terrier-lab mix, Poppy, barks through the screen door at a passing cat. Outside is a spread of Brussels sprout fields, a steel-blue ocean.

“To explain the need for the study of anatomy, I give my students this analogy,” Buchanan says, asking a visitor to imagine being an artist who must draw a still life of a sheet draped over a set of unknown objects. Then, the sheet would be pulled back to reveal the unknown objects and the artist would make a second drawing. The final drawing would be a still life of the original scene of sheet-draped objects.

“The third drawing you would make now is so much more informed by the underlying structure and reveals what is causing the surface of the sheet to behave as it does,” Buchanan says. “And you would find that this new drawing is profoundly more complex, intellectual, and natural.”

It is the same way with the human figure, he says.

Former students tell of Buchanan lecturing in front of his classes, sketching exquisite renderings of a human arm or a shoulder blade on sheets of brown paper as he describes the structure, name, and mechanical function of the muscles and bones in each.

“Each of the drawings he does, I want to frame and put in my house,” says Jill Steinberg, 65, a retired psychology professor from San Jose State University who describes Buchanan as a brilliant teacher who is respectful of each student.

“His work is interdisciplinary,” she says.

Roxanne Kaplan, 22 (Kresge ’15, art), who works at a fine arts studio in Mountain View, calls Buchanan “inspiring.”

“He gave me the foundation for all my future artwork,” Kaplan says. “Now that I know the guidelines for portraying the human form, I can consciously break set rules to generate certain feelings or messages.”

During Buchanan’s own time at UC Santa Cruz, he gravitated to Emeritus Art Professor Frank Galuszka, who encouraged him to depict the human figure in a narrative content.

“He pushed me to embrace the figure spiritually, mythically, and heroically,” Buchanan says. “Galuszka mentored me into more ambitious challenges of tackling multiple figure compositions with content, narrative, and meaning.”

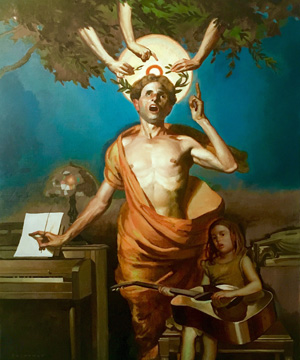

Next to Buchanan is a large work-in-progress he’s titled, “Apollo Crowned Glorious While Instructing a Child in the Art of Music.”

He looks at the painting, which harkens back to works by 17th century Spanish painter Diego Velazquez. “The human figure here,” he says, “is used for the purpose of recognition that within God is man and vice versa.”

A surfer, guitarist, and admitted throwback to the times of Carravagio and Titian, Buchanan has exhibited from New York to London, shows at the Robert Pence Gallery in San Francisco, and was commissioned to paint two large murals at the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in La Crosse, Wis.

“My principle passion in making figurative paintings is the idea of interface between the divine and the mortal, and I think that explains my passion for anatomy beyond the scientific,” Buchanan says.

“The more I study the human body, the more miraculous its design and structure become to me, and the more I stand in awe of the idea that, within the science of nature, is art.”

Noah Buchanan’s work will be exhibited in upcoming shows at the Sesnon Gallery April 7–May 7, 2016, with an opening reception on Thursday, April 7, from 5–7 p.m.; and at the Blitzer Gallery, with an opening reception on Friday, April 8 from 5–7 p.m.