Campus News

No reason to retire

In their 70s and 80s, many pioneer faculty are still working on campus—for the chance to open students’ eyes, for the excitement of discovery, and for the love of teaching.

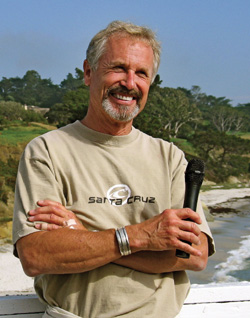

On a January day in 1969, Gary Griggs, then 25, donned a coat and tie and entered a lecture hall on the nascent UC Santa Cruz campus.

What he found inside were 260 scruffy but idealistic students — most of them long-haired, many with dogs. Griggs, who had finished his Ph.D. in three years and never taught before, stepped up and began his oceanography lecture. When he was finished, the entire room stood and applauded.

Almost five decades later, Griggs, now director of the Institute of Marine Sciences, has shed the coat and tie in favor of jeans and a button-down shirt. But at 71, Griggs is still youthful-looking and still at work.

This will be his 48th year teaching oceanography and 40th year teaching coastal geology: 14,000 students and 72 grad students by his count.

“What is amazing now is to think back about those first few years of flower children and realize that they are now 60-65 years old and have careers and families,” Griggs says. “In some cases, they’ve already retired, but I can’t find any reason to.”

Griggs is one of 18 pioneer faculty who came to UC Santa Cruz before 1970 and who are still actively involved in the campus. They continue to work, they say, because they love opening students’ eyes to the world around them, because they are excited by discovery, and because they believe being a professor is one of the best jobs around.

“A businessman can come home and say I made a million dollars today,” says G. William Domhoff, emeritus professor of psychology and sociology who has been teaching at UC Santa Cruz for 50 years. ”For me, the gratification is when a student comes up to me and says, ‘I think I learned something today.’”

Harry Noller: The excitement of the lab

Stand under the redwoods outside the Sinsheimer Labs building most mornings and you will see bushy-haired Emeritus Professor of Molecular, Cell and Developmental Biology Harry Noller heading to work.

At 76, Noller has retired from teaching, but the excitement of what is happening in his lab draws him like a thirsty man to water.

Noller, who came to UC Santa Cruz in 1968, is a decorated scientist who studies the ribosome, a kind of bilingual molecule that bridges the gap between DNA and RNA on one hand and proteins on the other. It is one of the core mysteries of science and is essential to all forms of life. Over the years, Noller’s research has turned the understanding of the mysterious ribosome on its head.

He discovered that the RNA component carries out key functions of the ribosome — the inverse of what most scientists believed. He has done atomic-level mapping of the structure of the ribosome, a basis for the development of targeted antibiotics. Now, he is piecing together the actual movements of the ribosome as it does its job.

“The thing is alive as you look at it,” Noller says, enthusiasm seeping into his words. “It is flexing and reaching to grab things and pulling them through at the atomic level. This is the basis of life. This is how the genetic code is read in all of our cells every minute.

“That’s what excites me,” Noller says. “That’s why I go to work every day.”

Adrienne Zihlman: The exhilaration of discovery

It is that same sense of excitement that keeps Professor of Anthropology Adrienne Zihlman on the job, three years after her supposed retirement.

Zihlman, 74, first shook up the field of anthropology with research that showed female gathering activities could just as easily account for our big brains as men’s hunting behaviors did. Then, at a time when the common chimpanzee was considered the model for the human-ape ancestor, she proposed that the rare pygmy chimpanzee was a better model in its anatomy and behavior.

While both these ideas were met with strong opposition at first, more evidence has made them generally accepted in academia today.

Now, Zihlman is pulling together decades of that research into a beautifully illustrated text — a kind of “Gray’s Anatomy” for apes.

Working with illustrator and former UC Santa Cruz student Carol Underwood, Zihlman’s tome will tell an evolutionary and anatomical tale designed for both scientists and lay people.

It’s the exhilaration of discovery, of shining a light on apes and evolution, that keeps Zihlman working.

Quoting Freud that “anatomy is destiny,” Zihlman added, “It’s also the key to the mystery of human evolution.”

David Kaun: The joy and pleasure of teaching

At 83, Emeritus Professor of Economics David Kaun is quick to laugh about why he will soon embark on his 50th year of teaching.

“I’m a labor economist,” he says. “I spent my entire career trying to figure out why people work.”

Kaun came to the campus in 1966 from a teaching job at the University of Pittsburgh, drawn by the beautiful setting and the offbeat experiment that was UC Santa Cruz. Like Griggs’s students, Kaun would usually bring his dog, a long-legged basset hound named Greta, to class.

But long after most retirees are lounging on cruise ships and driving across the country in motor homes, Kaun will be teaching two classes this year: one on the Political Economy of Capitalism and the other on the Economics of the Arts, a course born out of his love for music and his talent on the clarinet.

Kaun will also lead his popular Labor Wars in Theory and Film class, which leaves most of its students saying they can never quite watch a movie the same way again.

“I have been extremely fortunate, blessed, and lucky to wind up doing something that has been such a joy and pleasure,” says Kaun of his work.

“Besides, if you spend your life around 20-year-olds,” he says, “how can you possibly get old?”

G. William Domhoff: Explaining concepts leads to deeper insights

Psychology professor Domhoff feels much the same way.

Twenty-one years after his alleged retirement, the 79-year-old academic most known for his study of dreams and his work on the psychology of power, says student inquiries and the need to explain concepts in his field often bring new insights.

“In a dialogue with students, trying to explain something, makes you understand the subject better,” Domhoff says, “and that really matters to me.”

It’s part of the reason, besides being a member of an academic community, that Domhoff will teach two courses this year. He is also continuing work on a book that presents his theory of dreams as “a form of intensified mind-wandering that dramatizes an individual’s main, personal concerns.”

As one of only two working professors who began teaching the same year UC Santa Cruz was born — Emeritus Professor of Literature Harry Berger will teach a course on Plato in the spring — Domhoff finds satisfaction in his profession.

It’s the same gratification that became clear to Griggs when he learned that one of his students, a former language major named Kathryn Sullivan, credited part of her success to him.

Inspired by his oceanography course and Griggs’s answers to her many questions, she got her Ph.D. in that subject, went on to become the first American woman to walk in space, and is now undersecretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere and administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Sullivan will be master of ceremonies at UC Santa Cruz’s Founders Celebration Fiat Fifty dinner on September 26.

“It made … me appreciate how critically important our roles are at UCSC, or any university,” Griggs says. “It has been the rewards and satisfaction of events like this, and others, that continue to inspire and motivate me.”

Other pioneer faculty who continue to work at UC Santa Cruz include:

- Ralph Abraham

- Frank Andrews

- Murray Baumgarten

- Edmund Burke

- Robert Coe

- Walter Goldfrank

- John Jordan

- Peter Kenez

- H. Marshall Leicester

- Michael Nauenberg

- Harold Widom

- Donald Wittman

Pioneer staff and faculty will receive the Fiat Lux Award at this year’s Founders Celebration Fiat Fifty dinner.