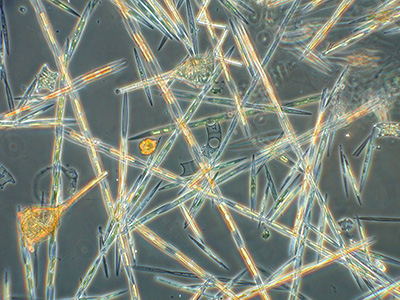

Researchers have detected large blooms of toxin-producing algae in Monterey Bay, raising concerns about potential effects on marine mammals and seabirds. The bloom involves microscopic algae called Pseudo-nitzschia (a type of diatom), which produce a potent neurotoxin called domoic acid. The toxin was first detected in early May, and by the end of the month researchers had detected some of the highest concentrations of domoic acid ever observed in Monterey Bay.

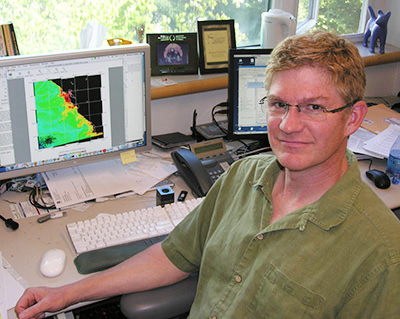

"It's a pretty massive bloom. The domoic acid levels are extremely high right now in Monterey Bay, and the event is occurring as far north as Washington state. So it appears this will be one of the most toxic and spatially largest events we've had in at least a decade," said Raphael Kudela, professor of ocean sciences and Ida Benson Lynn Chair of Ocean Health at UC Santa Cruz.

Periodic blooms of toxin-producing Pseudo-nitzschia diatoms have been documented for over 25 years in Monterey Bay and elsewhere along the U.S. west coast. During large blooms, the toxin accumulates in shellfish and small fish such as anchovies and sardines that feed on algae, forcing the closure of some fisheries and poisoning marine mammals and birds that feed on contaminated fish.

Warm water

Blooms such as the current event typically last for several weeks to a month. "Often, if we have a big event in the spring, it will go away during the summer and come back in the autumn," Kudela said. "This event may be related to the unusually warm water conditions we've been having, and this year that warm water has spread all along the west coast, from Washington to southern California."

Kudela leads a regional project that brings together researchers from several institutions to monitor study sites in Monterey Bay and southern California. His lab conducts weekly sampling of water and mussels at the Santa Cruz Wharf and works closely with the California Department of Public Health and other organizations. Although Pseudo-nitzschia blooms often affect wildlife, careful monitoring and fishery closures ensure that commercial seafood remains safe to eat.

During the May 2015 event, researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) measured concentrations of both Pseudo-nitzschia cells and domoic acid in the bay using robotic instruments called Environmental Sample Processors (ESPs), which are deployed on ocean moorings and can detect algal cells and toxins and send the results back to shore within an hour. Complementing the data from the ESPs, Kudela's lab analyzed water and animals collected from the bay for Pseudo-nitzschia cells and domoic acid, and UCSC has two robotic gliders collecting data from the surface to a depth of 200 meters in the bay. The University of Southern California also has two robotic vertical profilers, called Wire Walkers, deployed near the ESPs. Researchers from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories helped collect animals and water samples for analysis and are working with UC Santa Cruz researchers to continue monitoring blooms in the bay.

"We have confirmed domoic acid at very high levels in mussels and anchovy," Kudela said. His lab also found very high levels of the toxin in samples from a dead pelican found on the beach in Moss Landing, and testing of sea lion samples is under way. "Domoic acid has clearly worked its way into the food web," he said.

Forecasts

In addition to the regional monitoring project, which is funded by NOAA's Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms (ECOHAB) Program, Kudela's lab has also been developing predictive models to produce forecasts of where and when blooms of toxic algae will occur. With funding from NASA, the UC Santa Cruz researchers have been working with the Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System (CeNCOOS) to run the model and produce forecasts for the entire coast of California. Forecasts are currently available online through CeNCOOS. Over the next three years, Kudela said, his team will be working to hand the model over to NOAA to be run operationally through the National Weather Service supercomputers.

"They'll be coupling it with the weather models to provide forecasts saying what's likely to happen in the next three days," he said. "So far, it's been very good at picking out regional patterns, so we've seen very good correlations with sea lion strandings; but it's less good at pinpointing specific locations."

Clarissa Anderson, who was a postdoctoral researcher in Kudela's lab and is now a research scientist with the UCSC Institute of Marine Sciences, has been leading the work on predictive modeling. When the current domoic acid event began in Monterey Bay in May, the model was also predicting a bloom in coastal waters near Humboldt Bay in Northern California. Anderson, who happened to be up there to give a talk, got local researchers to collect samples for testing, and Kudela's lab was able to confirm the presence of domoic acid.

"We're now developing a model specifically for the shellfish growers in Humboldt Bay," Kudela said. "We know users are paying attention to it. In addition to shellfish growers, the Marine Mammal Center is also using it to keep an eye on spatial patterns and whether toxin levels are going up or down, so they know where and when to expect strandings."

Kudela's collaborators in the ECOHAB program include scientists at MBARI, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, CeNCOOS, UCLA, University of Southern California, Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, Southern California Ocean Observing System, and the U.S. National Centers for Coastal and Ocean Science.