An innovative graduate program on Science Hill is breaking down barriers between the biomedical sciences, encouraging interdisciplinary research, and enabling students from different departments and divisions to work closely together.

Now in its sixth year, the graduate Program in Biomedical Sciences and Engineering (PBSE) is a collaborative graduate program that includes faculty from five departments spanning the Divisions of Physical and Biological Sciences and the Baskin School of Engineering.

Originally, individual departments had their own graduate programs based on traditional disciplines, "but research has evolved to a point where students now employ techniques and logic from multiple disciplines to attack interesting problems in biomedical research," said current PBSE director Seth Rubin, chemistry and biochemistry professor.

"We needed a graduate program that reflects the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of biomedical research at UC Santa Cruz," said Doug Kellogg, Molecular, Cell and Developmental biology professor and PBSE's founding program director.

Before the creation of this program, graduate students would come in to a department and do their thesis work only with a professor within that department.

"If a student wanted to explore and learn multiple disciplines, that was hard," Kellogg said. "We wanted to eliminate compartmentalization to give students the freedom to explore. That's good for students and good for biomedical research."

In the past half-dozen years, PBSE has helped change the culture of Science Hill as well as the kind of student who is coming to UC Santa Cruz to study biomedical sciences.

"We have a really good, deeper, broader applicant pool,'' Kellogg said. "PBSE attracts students who are broad in their thinking, who think independently, who can make their own programs."

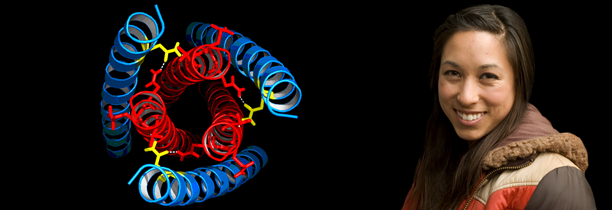

One example of this newer, cross-disciplinary approach is Rachel Doran, a 4th year graduate student, who is investigating the immune responses of people infected with HIV who do not succumb to normal progression of disease to learn how their antibody responses make them resistant to AIDS.

"I am a PBSE student who hopped on over from molecular biology to bioengineering to work in Professor Phil Berman's lab," said Doran, who is using her training in molecular biology to search for new ways to stop HIV. This kind of cross-disciplinary training prepares students to use whatever technical approaches that need to solve problems.

Another net benefit is the increased communication between students in the various departments. "Groups of students are really talking, and, most importantly, making contacts," Kellogg said. "If you have a problem in research down the line, you can say, 'Oh, I have this friend working in bioinformatics; I'll contact her to learn how to solve my bioinformatics problem.'"

The PBSE program has hosted several events to bring the entire cohort together and encourage interactions across tracks. A full-day retreat at the start of the academic year is attended by all departments and allows students to present research and get feedback from faculty and their peers. The program is also developing a common core course, focused on interdisciplinary problem solving and critical reading of the scientific literature, which will include all first-year students.

Communication about science even spills over into the social realm.

"Before, they weren't in the same courses," Kellogg said. "They wouldn't even know each other. Now, I'll walk downtown and see students from different tracks hanging out together."