The chemical uniformity of stars in the same cluster is the result of turbulent mixing in the clouds of gas where star formation occurs, according to a study by astrophysicists at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Their results, published August 31 in Nature, show that even stars that don't stay together in a cluster will share a chemical fingerprint with their siblings which can be used to trace them to the same birthplace.

"We can see that stars that are part of the same star cluster today are chemically identical, but we had no good reason to think that this would also be true of stars that were born together and then dispersed immediately rather than forming a long-lived cluster," said Mark Krumholz, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

Our sun and its siblings, for example, probably went their own ways within a few million years after they were born, Krumholz said. The new study suggests that astronomers could potentially find the sun's long-lost siblings even if they are now on the opposite side of the galaxy.

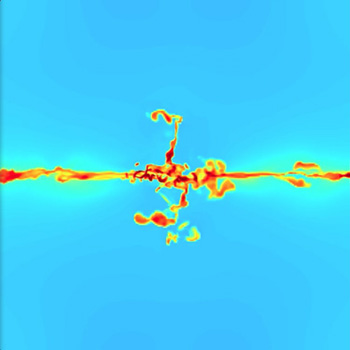

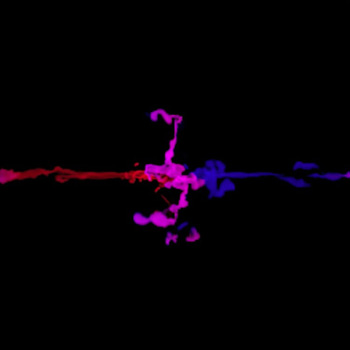

Krumholz and UC Santa Cruz graduate student Yi Feng used supercomputers to simulate two streams of interstellar gas coming together to form a cloud that, over the course of a few million years, collapses under its own gravity to make a cluster of stars. Studies of interstellar gas show much greater variation in chemical abundances than is seen among stars within the same open star cluster. To represent this variation, the researchers added "tracer dyes" to the two gas streams in the simulations. The results showed extreme turbulence as the two streams came together, and this turbulence effectively mixed together the tracer dyes.

"We put red dye in one stream and blue dye in the other, and by the time the cloud started to collapse and form stars, everything was purple. The resulting stars were purple as well," Krumholz said. "This explains why stars that are born together wind up having the same abundances: as the cloud that forms them is assembled, it gets thoroughly mixed. This was actually a bit of a surprise. I didn't expect the turbulence to be as violent as it was, so I didn't expect the mixing to be as rapid or efficient. I thought we'd get some blue stars and some red stars, instead of getting all purple stars."

Fast mixing

The simulations also showed that the mixing happens very fast, before much of the gas has turned into stars. This is encouraging for the prospects of finding the sun's siblings, because the distinguishing characteristic of stellar families that don't stay together is that they probably disperse before much of their parent cloud has been converted to stars. If the mixing didn't happen quickly enough, then the chemical uniformity of star clusters would be the exception rather than the rule. Instead, the simulations indicate that even clouds that don't turn much of their gas into stars produce stars with nearly identical chemical signatures.

"The idea of finding the siblings of the sun through chemical tagging is not new, but no one had any idea if it would work," Krumholz said. "The underlying problem was that we didn't really know why stars in clusters are chemically homogeneous, and so we couldn't make any sensible predictions about what would happen in the environment where the Sun formed, which must have been quite different from the environments that give rise to long-lived star clusters. This study puts the idea on much firmer footing and will hopefully spur greater efforts toward making use of this technique."

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and NASA.