More than a dozen nationally prominent climate scientists and policy makers gathered for the first Climate Science and Policy Conference at UC Santa Cruz Friday, February 28 and Saturday, March 1 organized by UCSC's divisions of Social Science and Physical and Biological Sciences.

The well-attended conference featured opening and closing keynote addresses by climate scientists Susan Solomon and Michael E. Mann and three panel discussions focused on the current state of climate research, mitigating the effects of climate change, and adapting to future effects.

Solomon, now at MIT, is a renowned atmospheric chemist who was the first to attribute the ozone hole to chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). She opened the conference Friday evening with the Fred Keeley Lecture on Environmental Policy and compared the challenge of climate change to past environmental challenges–specifically, lead pollution and the ozone hole–and finds hope in the way those challenges were met.

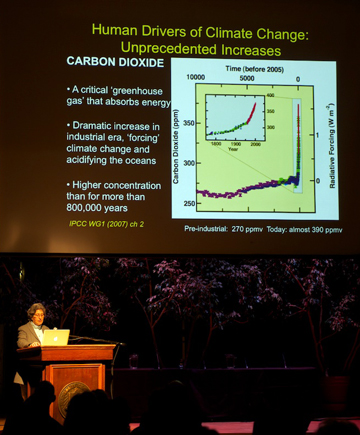

Climate change, however, is an especially daunting problem. She said we are accustomed to dealing with environmental pollution that is reversible but the changes happening now because of manmade carbon emissions (greenhouse gases) are largely irreversible for at least 1,000 years.

Bathtub effect

Solomon called this the "bathtub effect," because carbon emissions are like adding water to a tub much faster than it can drain. Because carbon is removed from the atmosphere so slowly, an 80 percent reduction in current emissions is needed by 2050 just to stabilize their concentration in the atmosphere.

Still, Solomon struck an optimistic tone. "There is only one way to get the 80 percent reduction we need and that's with new energy technology," Solomon said, noting that the United States remains the world leader in the development of innovative technologies.

Other speakers, most notably Steven Cohen, executive director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, echoed Solomon's call for a bigger investment in energy technology research and development.

"What's gotten us into this mess is human ingenuity. And that's what's going to get us out of it," Cohen said during the second panel discussion on Saturday.

Panelists grappled with, among other things, the thorny issue of attributing extreme weather events to climate change. While no single event can be directly attributed to human-caused climate change, an increase in the frequency of extreme events such as heat waves and destructive hurricanes and typhoons is consistent with predictions of climate models.

Science is clear

"The science is clear," said Mann in his closing keynote Saturday evening. Cold conditions are less common, warm conditions are more common, said Mann, distinguished professor of meteorology at Pennsylvania State University. "Climate change is real, it's caused by us, and it represents a threat."

Mann said the 30-year period from 1983 to 2012 is the warmest in the past 1,400 years and noted that Lisa Sloan, UCSC professor of Earth and planetary sciences, predicted 10 years ago some of the effects of climate change that the planet is now experiencing. Her 2004 paper with graduate student Jacob Sewall – “Disappearing Arctic sea ice reduces available water in the American west” – was published in the journal Geophysical Research.

In Saturday's opening session, moderator Paul Koch, UCSC dean of physical and biological sciences, asked which aspects of climate change projections are panelists most confident in. Jeffrey Kiehl, of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, pointed to the effects on temperature. He is least confident about projected changes in precipitation.

Climate modeler Gavin Schmidt, of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, noted the "intrinsic unpredictability" of rainfall. But increased temperatures have already resulted in a significant loss of Arctic sea ice, rising sea levels, and more water vapor in the atmosphere, he said, and it's clear that the warming trend will continue.

Kiehl said that if we continue on the current path of increasing greenhouse gas emissions, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will pass 1000 parts per million in about 90 years. The last time Earth's atmosphere had that much carbon dioxide was 30 million to 40 million years ago. "We know what the world was like then. It was a very different world, and the human species has never known that climate system," he said.

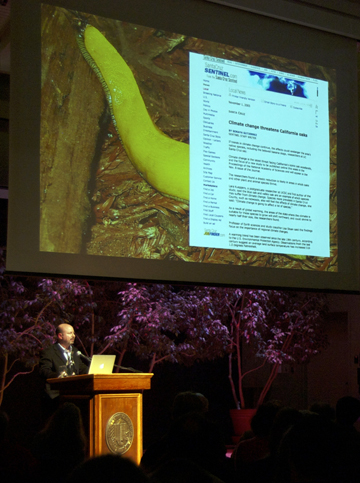

UCSC biologists Terrie Williams and Barry Sinervo described the dramatic effects climate change has on wildlife. Sinervo also noted the unintended consequences of mitigation measures such as massive solar arrays that can create "heat islands" that threaten the desert tortoise with extinction.

California's quiet revolution

California leads in efforts to cut fossil-fuel use and move to renewable energy sources.

A "quiet revolution" is going on now in the state, said Guido Franco, the climate change research lead at the California Energy Commission. Use of electrical power from coal-fired plants in other states is being phased out.

A 2006 law, AB 32, commits California to reducing carbon emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. We’re already a third of the way there said Ken Alex, a senior policy advisor to Gov. Jerry Brown and director of the state Office of Planning and Research, focusing on energy, environment, and land use issues.

Alex is also a UCSC grad ('79, Stevenson, politics) and told attendees in the College Nine/10 multipurpose room how happy he was to be on campus again. "I feel very much at home," he said.

Also attending portions was John Laird (Stevenson, 71, politics), secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency.

Alex made the point that while California has the world's eighth largest economy and 38 million people, "who cares what California does" when the emerging economies of China and India have 2.8 billion people. Answering his own question, Alex said innovations and changed behavior in California can have widespread influence.

Social Sciences Dean Sheldon Kamiekiecki said he was very pleased by the level of discussion and the turnout at the Climate Science conference, and said he hopes it is the first of many.