Campus News

Stanford, UCSC study predicts oil demand to peak around 2035

Fears of depleting the Earth’s supply of oil are unwarranted, according to new research, which describes instead a coming peak and decline in demand for oil.

Fears of depleting the Earth’s supply of oil are unwarranted, according to new research, which describes instead a coming peak and decline in demand for oil.

“Peak oil” prognosticators have painted pictures of everything from a calm development of alternatives to calamitous shortages, panic and even social collapse. But, according to the study by researchers at Stanford University and UC Santa Cruz, those scenarios assume that an increasingly wealthy world will immediately use all oil pumped out of the ground. Instead, the historical connection between economic growth and oil use is breaking down—and will continue to do so—because of the limits of consumption by the wealthy, better fuel efficiency, lower priced alternative fuels and the world’s rapidly urbanizing population.

“There is an overabundance of concern about oil depletion and not enough attention focused on the substitutes for conventional oil and other possibilities for reducing our dependence on oil,” said study lead author Adam Brandt, professor of energy resources engineering at Stanford University’s School of Earth Sciences.

Variety of mechanisms

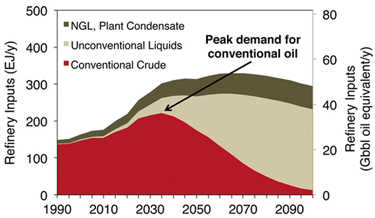

The study, published in Environmental Science & Technology, describes a variety of mechanisms that could cause society’s need for oil to peak around 2035 and then decline. Several earlier studies have suggested that passenger land travel has already plateaued in industrialized countries and is no longer hitched to economic growth. Passenger land travel accounts for about half of global transportation energy demand currently. Even in developing countries, economic growth has been less oil intensive than was seen in the West the past century. China, for example, sells 20 million electric scooters to its citizens a year as part of the government’s policy to reduce air pollution. That exceeds total U.S. passenger vehicle sales annually.

“We’ve seen explosive growth in car ownership in countries such as China,” said co-author Adam Millard-Ball, UCSC assistant professor of environmental studies. “However, those cars will be more efficient than those of the past, and travel demand will eventually saturate as it has in rich countries such as the United States.”

Freight and air travel

Freight and air travel have shown no such break from economic growth. Rich people may not drive more beyond a certain income level, but they do fly more and buy more stuff, as do people moving out of poverty. Even in air travel and freight, though, energy efficiency has begun to improve after decades of stagnation, which is lowering oil dependence, according to the new study.

“A major uncertainty is whether demand to move goods around the world will eventually saturate, as we’ve seen in the case of passenger transport,” said Millard-Ball.

Price-competitive alternatives are another factor behind the peak in demand for conventional oil. Increasing quantities of conventional oil substitutes are being produced, including low-quality fuel from oil sands, liquid fuels from coal, natural gas, biofuels, hydrogen and electricity. Technological advances and the high price of oil are helping most such alternatives compete on price. In 2010, the world produced 1.8 million barrels a day of biofuels, six times the amount in 2000. In Argentina, natural gas fuels 15 percent of all cars, due to policies meant to favor the domestic natural gas industry.

The researchers did not try to forecast peak demand’s impact on oil prices. But even if oil prices spend much time above the historical upper range of $140 a barrel, the peak in demand will only come sooner than they forecast.

“If prices rise above their current levels for an extended period, we’re likely to see even more efforts to improve efficiency and exploit alternatives to conventional oil,” Millard-Ball said. “That would hasten the onset of a demand-driven peak.”

Oil alternatives

The new research, though encouraging, does not describe a transportation future free of worry. Instead, the researchers recommend a shift in attention to the various alternatives to conventional oil. Policymakers should not rely on oil scarcity to constrain damage to the world’s climate, for example. Alternatives to conventional oil, such as oil sands, liquids from coal and natural gas, biofuels and electricity from renewable sources emit very different amounts of greenhouse gases. At the same time, large scale production of biofuels could have a disruptive impact on food prices and on local ecosystems where the plants are grown.

“If you care about the environment, you should care about where we are getting these fuels, whether we use the oil sands or biofuels,” said Brandt. “Our study is agnostic on what mix of oil substitutes emerges, but we do know that if we don’t manage them well, there will be big consequences.”

The study forecasts global oil demand every five years through 2100, under a variety of scenarios for economic growth, population, efficiency gains and fuel substitution. Interested parties can use the study’s model, inputting their own set of assumptions at http://pangea.stanford.edu/researchgroups/eao/research/oil-substitution-and-decline-conventional-oil.

The study’s other co-authors are Steven Gorelick, Stanford professor of environmental Earth systems science, and Matthew Ganser, director of engineering at Carbon Lighthouse,