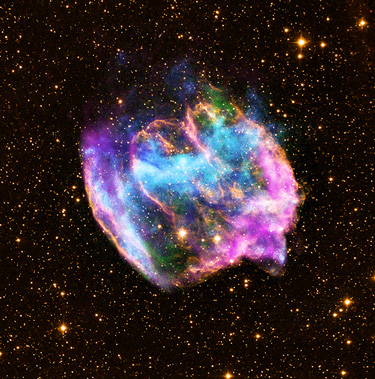

New data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory suggest a highly distorted supernova remnant may contain the most recent black hole formed in the Milky Way galaxy. The remnant appears to be the product of a rare explosion in which matter is ejected at high speeds along the poles of a rotating star.

The remnant, called W49B, is about a thousand years old as seen from Earth and located about 26,000 light-years away.

"W49B is the first of its kind to be discovered in the galaxy. It appears its parent star ended its life in a way that most others don't," said astronomer Laura Lopez, who led the study. Now an Einstein Postdoctoral Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lopez earned her Ph.D. at UC Santa Cruz working with Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, professor of astronomy and astrophysics and a coauthor of the study.

Usually when a massive star runs out of fuel, the central region of the star collapses, triggering a chain of events that quickly culminate in a supernova explosion. Most of these explosions are generally symmetrical, with the stellar material blasting away more or less evenly in all directions.

In the W49B supernova, however, material near the poles of the doomed rotating star was ejected at a much higher speed than material emanating from its equator. Jets shooting away from the star's poles mainly shaped the supernova explosion and its aftermath.

The remnant now glows brightly in x-rays and other wavelengths, offering the evidence for a peculiar explosion. By tracing the distribution and amounts of different elements in the stellar debris field, researchers were able to compare the Chandra data to theoretical models of how a star explodes. For example, they found iron in only half of the remnant while other elements such as sulfur and silicon were spread throughout. This matches predictions for an asymmetric explosion.

"In addition to its unusual signature of elements, W49B also is much more elongated and elliptical than most other remnants," said Ramirez-Ruiz. "This is seen in x-rays and several other wavelengths and points to an unusual demise for this star."

Because supernova explosions are not well understood, astronomers want to study extreme cases like the one that produced W49B. The relative proximity of W49B also makes it extremely useful for detailed study.

The authors examined what sort of compact object the supernova explosion left behind. Most of the time, massive stars that collapse into supernovas leave a dense, spinning core called a neutron star. Astronomers often can detect neutron stars through their x-ray or radio pulses, although sometimes an x-ray source is seen without pulsations. A careful search of the Chandra data revealed no evidence for a neutron star. The lack of such evidence implies a black hole may have formed.

"It's a bit circumstantial, but we have intriguing evidence the W49B supernova also created a black hole," said coauthor Daniel Castro of MIT. "If that is the case, we have a rare opportunity to study a supernova responsible for creating a young black hole."

Supernova explosions driven by jets like the one in W49B have been linked to gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) in other objects. GRBs, which have been seen only in distant galaxies, also are thought to mark the birth of a black hole. There is no evidence the W49B supernova produced a GRB, but it may have properties, including being jet-driven and possibly forming a black hole, that overlap with those of a GRB.

The new results on W49B, which were based on about two-and-a-half days of Chandra observing time, appear in a paper in the Astrophysical Journal. The other coauthor was Sarah Pearson from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., manages the Chandra Program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory controls Chandra's science and flight operations from Cambridge, Mass.