Campus News

Alumni Profile / Steve Collins: A ‘real’ rocket man

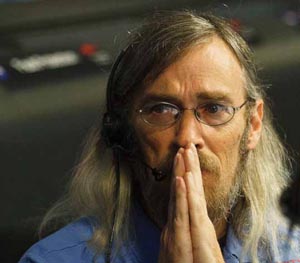

As the one-ton rover, Curiosity, rushed toward the surface of Mars for a landing that was part dance, part crazy science, someone snapped a picture of Steve Collins.

As the one-ton rover, Curiosity, rushed toward the surface of Mars for a landing that was part dance, part crazy science, someone snapped a picture of Steve Collins.

His long hair clouding around him, his hands posed prayer-like, Collins was captured in the moment of wondering whether the project on which he had worked for close to five years would be a spectacular success or a humiliating disaster.

That photo of Collins (Porter ’85, physics and theater arts) became a national symbol after the August 5 touchdown, not only of remarkable accomplishment, but also of the new face of aerospace. No more men with crew cuts and ties à la Apollo 13. This group had women, and guys with mohawks and long hair. They were cool and adventurous—they were mavericks, just as Collins is in real life.

Besides his work at the Jet Propulsion Lab, which nestles in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains near Los Angeles, the 53-year-old polymath is also an actor who has appeared in numerous plays. He is a dancer/ choreographer, a soccer player, an autocross racer and a musician in an indie-rock band.

“I’m curious about things in a cross-disciplinary way,” he said simply.

The son of an Emmy-winning cinematographer and a music industry professional, Collins was fascinated both by space and entertainment.

He chose UC Santa Cruz because of its astrophysics and theater arts programs.

“It was a place where the physics people wouldn’t freak out when I put on tights to take modern dance,” he said.

His advisor, Physics Professor Emeritus Peter Scott, allowed him to do a rather unorthodox senior thesis on orbital rendezvous, which required him to learn computer programming. “He was very self-motivated to do unusual things, and to do them well,” Scott said of Collins.

The skills Collins acquired at UCSC landed him a job after graduation with a “mom-andpop” aerospace company. In 1992, he was hired at the Jet Propulsion Lab.

His job as an “attitude control” engineer is to keep spacecraft pointed in the right direction, perform trajectory corrections, and figure out “what the heck just happened,” he said.

On the Deep Space One project, for instance, Collins helped fly the revolutionary, ion-propelled spacecraft toward the comet Borrelly. On the way, however, the spacecraft’s star-tracker instrument failed, basically blinding those guiding it. Over the next months, Collins and five others cobbled together a way to successfully fly the craft without the crucial sensor.

When Curiosity developed a strange “wiggle” as it flew toward Mars, Collins solved that problem too. Heaters on the propellant tanks caused the shimmy, he said. It didn’t interfere with the mission.

During his career, Collins has helped deliver twin rovers to the surface of Mars, capture spectacular photos of Jupiter and its moons, send a spacecraft on a flyby of the Hartley-2 comet, and pilot the rover, Curiosity, to Mars with an innovative “sky-crane” landing system that allows spacecraft to settle in smaller and more discovery-rich areas.

Besides rocket science, Collins also regularly hits the stage as part of TACIT, Caltech’s resident theater company. He has done Shakespeare and musicals. In 2009, he played Galileo in Life of Galileo. He also is fullback for the JPL Cosmics soccer team, races his Mazda Miata through tricky autocross courses, plays the eerie-sounding theremin in a band called Artichoke, and choreographs dance routines.

It was the openness of UCSC, he said, that allowed him to explore his varied interests, and eventually land his “dream job.”

“At other, more structured schools, I think I could have gotten sideways with their expectations,” he said in a telephone interview. “Plus, Santa Cruz was a glorious place to live.”

—Peggy Townsend is a freelance writer based in Santa Cruz.