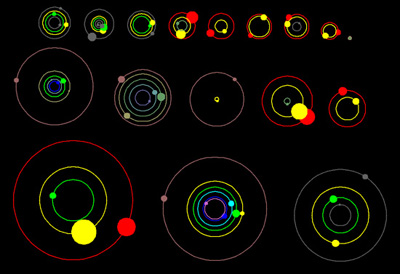

NASA's Kepler mission has discovered 11 new planetary systems hosting 26 confirmed planets. These discoveries nearly double the number of verified Kepler planets and triple the number of stars known to have more than one planet that transits, or passes in front of, its host star. Such systems will help astronomers better understand how planets form.

The planets orbit close to their host stars and range in size from 1.5 times the radius of Earth to larger than Jupiter. Fifteen of them are between Earth and Neptune in size, and further observations will be required to determine which are rocky like Earth and which have thick gaseous atmospheres like Neptune. The planets orbit their host star once every six to 143 days. All are closer to their host star than Venus is to our sun.

Each of the newly-verified planetary systems contains two to five closely-spaced transiting planets. Daniel Fabrycky, a Hubble Fellow at UC Santa Cruz and lead author of a paper confirming four of the systems, constructed dynamical models of how the planets pull on each other gravitationally.

"In tightly-packed planetary systems, the gravitational pull of the planets among themselves causes one planet to accelerate and another planet to decelerate along its orbit, and that causes the orbital period of each planet to change," Fabrycky said. "By precisely timing when each planet transits its star, Kepler detected the gravitational tug of the planets on each other, clinching the case for ten of the newly announced planetary systems."

Five of the new systems (Kepler-25, Kepler-27, Kepler-30, Kepler-31, and Kepler-33) contain a pair of planets where the inner planet orbits the star twice during each orbit of the outer planet. Four of the systems (Kepler-23, Kepler-24, Kepler-28 and Kepler-32) contain a pairing where the outer planet circles the star twice for every three times the inner planet orbits its star.

"These configurations help to amplify the gravitational interactions between the planets, similar to how my sons kick their legs on a swing at the right time to go higher," said Jason Steffen, the Brinson postdoctoral fellow at Fermilab Center for Particle Astrophysics in Batavia, Ill., and lead author of another paper confirming four of the systems.

Kepler has identified more than 2,300 planet candidates by repeatedly measuring the change in brightness of more than 150,000 stars to detect when a planet passes in front of the star, casting a small shadow toward Earth and the Kepler spacecraft.

The properties of a star provide clues for planet detection. The dip in brightness and duration of a planet transit combined with the properties of its host star present a unique signature. When astronomers detect candidates that exhibit similar signatures around the same star the likelihood of the planet being a false positive is very low.

Planetary systems with transit timing variations can be verified without requiring ground-based observations, accelerating confirmation of planet candidates. This detection technique also increases Kepler's ability to confirm planetary systems around fainter and more distant stars.

The system with the most planets among these discoveries is Kepler-33, a star that is older and more massive than our sun. Kepler-33 hosts five planets, ranging in size from 1.5 to 5 times that of Earth and all located closer to their star than any planet is to the sun.

"The approach that was used to verify the Kepler-33 planets shows that the overall reliability of Kepler's candidate multiple-transiting systems is quite high," said Jack Lissauer, planetary scientist at NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., and lead author of the paper on Kepler-33. "This is a validation by multiplicity."

These discoveries will be published in the Astrophysical Journal and the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The lead authors for the four papers are: Eric Ford, associate professor of astronomy at the University of Florida and lead author for Kepler-23 and Kepler-24; Jason Steffen, lead author for Kepler-25, 26, 27 and 28; Daniel Fabrycky, lead author for Kepler-29, 30, 31 and 32; and Jack Lissauer, lead author for Kepler-33.

Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., manages Kepler's ground system development, mission operations and science data analysis. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., managed the Kepler mission's development.

For more information about the Kepler mission and to view the digital press kit, visit: www.nasa.gov/kepler.

This video shows the known planetary systems with more than one planet transiting. They were all discovered by NASA's Kepler mission. The relative sizes of the orbits are correct, and the relative sizes of the planets are correct, but the scales differ. The positions are as they would be if all these planets were on circular orbits in the same plane. The time span shown is the first 1.5 years of science data from Kepler, and the spacecraft's perspective is from the "bottom" of the screen. Credit: Daniel Fabrycky