Physicists at the University of California, Santa Cruz, are working with medical researchers at Loma Linda University Medical Center to develop a new imaging technology to guide proton therapy for cancer treatment.

Proton therapy is a type of radiation therapy that allows powerful doses of radiation to be delivered directly to a tumor with little damage to the surrounding healthy tissues. Currently, images and data for planning and guidance of proton therapy are obtained from x-ray computed tomography (commonly known as a CT scan or CAT scan). But using information from x-rays to guide proton beams results in uncertainties that limit the accuracy with which the tumor can be targeted.

To overcome these limitations, researchers at the Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics (SCIPP) at UC Santa Cruz and their collaborators have been working since 2003 to develop the technology needed to perform proton computed tomography. This technology uses proton beams in the same way that x-rays are used in a regular CT scan.

"We have spent our whole careers building detectors to record charged particles, so we knew we could built a detector for proton tomography, and now we have a working prototype," said Hartmut Sadrozinski, a research physicist who leads work on the project at SCIPP.

A new four-year, $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health is funding current efforts to translate proton CT from the physics laboratory to clinical application, with about half of the funding going to UC Santa Cruz. Dr. Reinhard Schulte, an associate professor of radiation medicine, leads the project at Loma Linda, where the world's first hospital-based proton therapy center was built in 1990.

X-rays and proton beams have similar biological effects on cells, causing radiation damage to molecules within the cells. The increased susceptibility of cancer cells to radiation damage allows selective destruction of tumor cells with x-rays. But x-rays affect all of the tissues along the path of the x-ray beam through the body, whereas a proton beam can be tuned to deposit its energy mostly in a targeted area where the tumor is, with virtually no energy deposited beyond the target. This allows the use of higher radiation doses in proton therapy than can be safely used in x-ray therapy. It is also possible, if a tumor is adjacent to a critical structure in the body, to direct the proton beam so that it stops in the tumor without entering or causing any damage to the adjacent tissue behind the tumor.

The trick is to give the protons just the right amount of energy so that they will stop within the targeted area. An x-ray CT scan provides high-resolution images of the tumor and surrounding tissues, but it does not provide all the information needed to predict the exact range of protons passing through the tissues. With proton CT, it should be possible to design proton therapy to deliver radiation doses that conform precisely to the shape of the tumor on a daily basis.

"For proton CT, we tune the proton beam so that it passes through the patient, and we measure the residual energy in the protons, which tells us how much energy was lost," Sadrozinski said. Computed tomography techniques can then generate a three-dimensional picture of how the tissues in the body interact with the proton beam. "Then you can set the energy of the proton beam so that the protons stop right in the tumor."

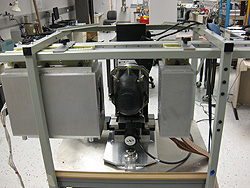

The current proton CT prototype , which was built at SCIPP with support from Loma Linda University Medical Center and Northern Illinois University, is being tested on models of the human body (known to radiologists as "phantoms") and has not been used on actual patients. Researchers are focusing now on increasing the speed of the imaging process in order to limit radiation exposure and reduce the amount of time a patient would have to spend in the scanner. "We want to match the speed of a normal CT scan," Sadrozinski said.

Sadrozinski and Robert Johnson, professor of physics at UC Santa Cruz, used the same "silicon strip" detector technology for this project that they and other SCIPP researchers used to build detectors for major particle physics instruments, including the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and the ATLAS detector at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. The SCIPP team developed specialized readout electronics for proton CT, and the researchers also plan to incorporate technology being developed at SCIPP for the next upgrade of the LHC.

More than a dozen UCSC undergraduate students have contributed to the project over the past ten years, Sadrozinski said. "A lot of senior theses have come out of this work," he added.

In addition to Sadrozinski and Schulte, the principal investigators on the NIH grant include Vladimir Bashkirov, director of the radiation research physics core laboratory at Loma Linda University, and Keith Schubert, professor of computer science at California State University, San Bernardino.