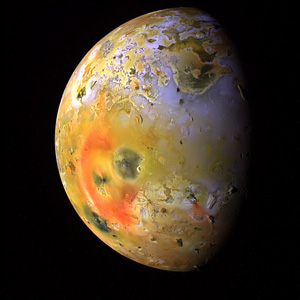

A new analysis of data from NASA's Galileo spacecraft reveals a subsurface "ocean" of magma--either molten or partially molten--beneath the surface of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io. The finding, from a study published this week in the journal Science, is the first direct confirmation of such a magma layer at Io and explains how Io can be the most volcanic object known in the solar system. The research was conducted by scientists at UCLA, UC Santa Cruz and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Coauthor Francis Nimmo, associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz, said that all rocky planets probably started out like Io--volcanically active and mostly molten on the inside. "People have generally assumed that Io's interior is partly molten because of its prodigious volcanic activity, but this study is the first to actually measure how much melt is present and where it's located," he said.

"Scientists are excited that we finally understand where Io's magma is coming from and have an explanation for some of the mysterious signatures we saw in some of the Galileo's magnetic field data," said Krishan Khurana, lead author of the study, former co-investigator on Galileo's magnetometer team, and a research geophysicist at UCLA. "It turns out Io was continually giving off a 'sounding signal' in Jupiter's rotating magnetic field that matched what would be expected from molten or partially molten rocks deep beneath the surface."

Io's volcanoes are the only known active magma volcanoes in the solar system other than those on Earth. Io produces about 100 times more lava each year than all the volcanoes on Earth. While Earth's volcanoes occur in localized hotspots like the "Ring of Fire" around the Pacific Ocean, Io's volcanoes are distributed all over its surface. A global magma ocean under about 20 to 30 miles (30 to 50 kilometers) of Io's crust helps explain the moon's activity.

"It has been suggested that both the Earth and moon may have had similar magma oceans billions of years ago at the time of their formation, but they have long since cooled," said Torrence Johnson, who was the Galileo project scientist, based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, and was not directly involved in the study. "Io's volcanism informs us how volcanoes work and provides a window in time to styles of volcanic activity that may have occurred on the Earth and moon during their earliest history."

Io's volcanoes were discovered by NASA's Voyager spacecraft in 1979. The energy for the volcanic activity comes from the squeezing and stretching of the moon by Jupiter's gravity as Io orbits the largest planet in the solar system.

Galileo was launched in 1989 and began orbiting Jupiter in 1995. After a successful mission, the spacecraft was intentionally sent into Jupiter’s atmosphere in 2003. The unexplained signatures in the magnetic field data occurred during Galileo flybys of Io in October 1999 and February 2000, during the final phase of the mission. "But at the time, models of the interaction between Io and Jupiter's immense magnetic field, which bathes the moon in charged particles, were not yet sophisticated enough for us to understand what was going on in Io's interior" said Xianzhe Jia, a coauthor of the study at the University of Michigan.

The magma ocean layer on Io appears to be more than 30 miles (50 kilometers) thick, making up at least 10 percent of the moon's mantle by volume. The blistering temperature of the magma ocean probably exceeds 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit (1,200 degrees Celsius).

The Galileo mission was managed by JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, for NASA.