Campus News

Reading and inspiration: Tobias Wolff at UCSC

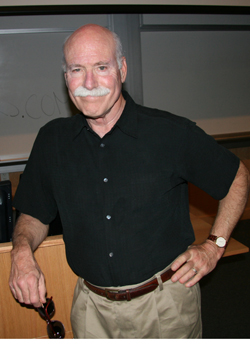

Tobias Wolff drew a capacity crowd to the Humanities Lecture Hall on the first night of the 2011 Living Writers series. Wolff read three short stories and regaled the crowd with stories of “binge reading” and his earliest inspirations as an author.

Tobias Wolff wishes he could say that reading Thomas Mann started him out on the road to becoming an author. He remembers reading an interview with Susan Sontag in which she talked about reading Mann and Kierkegaard when she was still in grade school.

“She was very precocious,” he said, dryly, during his opening remarks at the first night of the Humanities Division’s Living Writers reading series, which drew a capacity crowd to the Humanities Lecture Hall on Thursday.

Every one of us has an author like that, said Wolff, author of the novels The Barracks Thief and Old School, the memoirs This Boy’s Life and In Pharaoh’s Army, and the short story collections In the Garden of the North American Martyrs, Back in the World, and The Night in Question.

“You look back and think about who it was that made you store up extra batteries in your flashlight so you could stay up reading, and put towels under the doorway so your parents couldn’t see the light shining in the room.”

For Wolff, a creative writing and English professor at Stanford University, that man was Albert Payson Terhune, a writer and dog breeder who surrounded himself with collies, which he described as a “tawny swarm.” Terhune found fame writing genre fiction about his dogs – with many of narratives told from the point of view of the dog.

On Thursday night, Wolff talked about the way an author can store up readings, encounters and experiences over time and how these things can make their way into a creative work years later, taking the writer by surprise. Terhune’s books were the first “reading binge” Wolff ever went on.

Though Wolff now thinks Terhune was “probably certifiable,” he found himself drawn right back to those collies with one of his latest stories, “Her Dog,” in which a man has a prolonged conversation with his dead wife’s dog. Together they converse about fidelity, marriage, mortality and friendship, and have a tense standoff with a vicious dog and its thuggish – and curiously litigious – owner.

“I could not have written this story without Albert Payson Terhune,” Wolff said.

All those childhood reading binges finally paid off, more than five decades after the fact.

Wolff’s observations should encourage aspiring authors who feel sheepish about their early influences.

But he also offered encouragement to writers whose stories or books have run into dead ends. Sometimes, there is a missing ingredient that is just waiting to present itself and help you finish the story. That was the case for one of his most famous short works, “A Bullet In The Brain,” about Anders, a self-satisfied book critic who is caught in the middle of a deadly bank robbery.

Wolff, responding to the request of a young student, read that work out loud on Thursday. The story starts out linear and straightforward, and seems to stop dead about halfway through. “But wait, there’s more,” Wolff told the audience at the moment when the story goes from point-by-point to a more associative “dream time” structure.

It took years for the story to find its ending. The bank robbery scenario – and the doltish language of the robbers, who seem to have learned every one of their bank-robbing moves and speech mannerisms from television crime shows – was inspired by a friend’s account of a real-life Wells Fargo bank robbery. Wolff, digging for details, was “deeply disappointed … From the way my friend described it, it was one cliché after the other.”

On reflection, Wolff was glad he wasn’t at that bank that day. He wondered what would have happened if he was standing in the line, snickering helplessly and making “ironic judgment” about the robbers’ speech and mannerisms. “Anders is modeled on some aspect of my own character.”

But this was not enough to complete the story. Wolff “followed it up” by doing some research on the human brain. “Somehow, the completion of the story had to wait until I had the thing that would give it life. It was a long way around the barn.”

Joaquin Mayer, a 22-year-old creative writing major and UCSC senior, was honored to introduce Wolff on Thursday night.

“The short story ‘Bullet In The Brain’ showed me how to incorporate significant detail and back story,” said Mayer, who described the story as a creative writing master class. “The story’s words and images stuck in my head long after I finished it. I still have the original copy. The edges are disintegrating.”