Campus News

Destiny and development in the Mayan tradition of midwifery

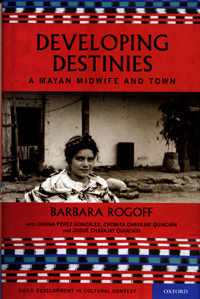

Barbara Rogoff is accustomed to choosing what she will write about. But with her most recent book, “Developing Destinies: A Mayan Midwife and Town,” the project chose her. The book is part memoir, part ethnography, part research study in child developmental psychology. It’s also clearly a labor of love.

Barbara Rogoff is accustomed to choosing what she will write about. But with her most recent book, Developing Destinies: A Mayan Midwife and Town (Oxford University Press, 2011) the project chose her.

The book is part memoir, part ethnography, part research study in child developmental psychology. It’s also clearly a labor of love for the UCSC Foundation Distinguished Research Professor of Psychology at UC Santa Cruz. It’s also been a long labor, the result of 20 years gestation and the culmination of research dating back to the mid 1970s.

Rogoff will present a reading from her book at the Bay Tree Bookstore at noon on May 12.

Labor and love figure prominently, as do destiny and development. In 1974, Rogoff, then a graduate student, was hired to give cognitive tests to children in the Mayan town of San Pedro la Laguna, Guatemala. There she met and interviewed Encarnación (Chona) Pérez González, a prominent and renowned sacred Mayan midwife, then nearly 50. In the Mayan culture, sacred midwives, known as iyoom, are identified at birth by the midwife who delivers them, who notifies the family that this is the baby’s destiny.

As a developmental psychologist, Rogoff interviewed Chona as the town’s leading childrearing expert. “When I first interviewed her about childrearing, I noticed her hands and commented ‘your hands look just like my mother’s,’” Rogoff recalls. “She replied, “That’s because I am your mother.’” Chona recounts to others in San Pedro that she gave birth to Rogoff. The result is a “mother and daughter relationship” that has spanned the decades, one that has given Rogoff intimate access to the traditional practices of midwifery. Rogoff has returned to the little town on the shores of Lake Atitlan nearly every year since that first visit except for a decade when her own children were young and violent political turmoil made it too dangerous.

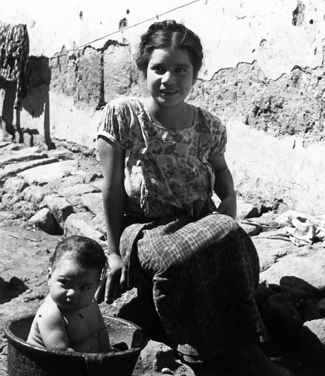

Developing Destinies contains 90 photographs, many of Rogoff’s own, but also a trove dating back to 1941 taken by anthropologists Lois and Ben Paul, which includes photographs of Chona as a young woman. The photographs and narrative document the changes to the town and its residents over more than 70 years as modernity crept in.

Twenty years ago, Rogoff and Chona decided to write the book. “The project kind of came along and said ‘you need to do this,’” Rogoff said. At first she wanted to paint watercolors of the town and people to illustrate a children’s book. But it soon became clear it wasn’t a children’s book and “gradually morphed into a book for a broad range of adult readers, including the general public.”

“It was a side project for most of that time,” Rogoff said. “I didn’t see it as something directly connected to my central work until recently.” But each year when she returned to San Pedro the project “reminded me, and I’d ask more questions.”

As she writes: “The story kept insisting on being written.”

Rogoff wrote the book with Chona (though she can neither read nor write) and Chona’s granddaughter, Chonita Chavajay Quiacaín, also born to be a sacred midwife, and grandson, Josué Chavajay Quiacaín, a sociologist.

Rogoff still has close ties to the town, she founded the town library, and helped develop an Internet learning center. Royalties from book sales will benefit the learning center and other projects in the town.

She plans to return to San Pedro in June and will present the book at the learning center. It is published only in English at this point but translations into Spanish and the Mayan language Tz’utujil are planned.

She’s even thinking of setting up a little table in the town market. “People can come along and see the book. They won’t be able to read it but they’ll be able to see the photos, which people from San Pedro regard as an important local archive.”