He finally had had enough.

Like millions of other young Arabs, Mohammad Bouazizi, age 26, had been repeatedly humiliated.

He could not find a decent job.

To survive, he sold vegetables on the street of the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid.

The authorities repeatedly harassed and abused him. Finally, he immolated himself in protest on December 17, 2010.

And thus the match was lit and touched to the tinder of a young, savvy, and enraged generation. The fire spread, as other youth in the town protested against penury and oppression, corruption and humiliation. The regime resorted to violence— but the rebels were undeterred. The revolt spread to the capital, Tunis, and after weeks of demonstrations, the dictator Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia in February.

Critically, this generational revolt spread next to Egypt, home of one-third of all Arabs. Years of struggle and organizing by opposition movements, liberal, socialist, and Islamist, culminated in the dramatic 18 days in which the corrupt, brutal regime of Hosni Mubarak was toppled. Similar revolts have spread (as of this writing) to Bahrain, Oman, Yemen, and Libya, as well as to Morocco, Algeria, Jordan, Iraq, and Iran.

Why did this happen? What are its implications for Americans? Two kinds of causes may be identified—immediate ("sparks") and structural ("tinder"). The sparks are sketched above—and a key component, in each case, is the triumph over fear—when an illegitimate, widely despised regime resorts to violence, and the protestors refuse to back down, the regime is doomed.

Structural causes are numerous. They include the fact that some 60 percent of Arabs today are younger than 30. They are by far the most educated generation in the region's history. Millions are unemployed, and food prices are rising. In both Tunisia and Egypt, the revolutions of 2011 were preceded—and accompanied by—widespread labor protests.

Most fundamentally, however, most Arabs despise their regimes—for their corruption, nepotism, violence, and complicity in American and Israeli abuses of power. Arab dictators have humiliated their peoples for decades. Finally, when the spark was struck, the tinder ignited. Modern social media facilitated the spread of revolt.

In today's world, everyone knows what is going on, everywhere.

Some say that today's Arab revolution confronts Americans with a choice between our values and our interests. Our values are, of course, democratic. But Arab democracy does not threaten our "interests," if "our interests" are the interests of the vast majority of Americans, rather than those of the (very well-heeled) minorities that profit from an Empire of foreign bases, pretensions to "control oil," and mindless support of unsustainable Israeli occupation policies.

From conflating Arab nationalists with friends of the USSR during the Cold War to positing non-existent WMD in Iraq, the U.S. record of interventions in the region is one of countering threats that did not in fact exist. Arab democracy is no threat. On the contrary, the revolt of Arab youth against humiliation should make anyone pledging allegiance to the principles of 1776 very proud, indeed.

Moments such as the present where many vectors of change come together in unpredictable ways are fraught with peril. This is no time for ill-conceived U.S. interventions, which can seriously harm our long-term interests. In the face of this massive uncertainty and unpredictability, we should recall the Hippocratic Oath: "First do no harm."

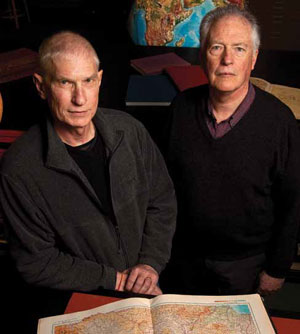

Alan Richards, professor emeritus of environmental studies, is an economist and an expert on energy politics. In 1989–91, he was an Education Abroad Program director in Cairo.

Edmund Burke III is research professor of history, emeritus, and director of the Center for World History.

Uncommon People / Alan Richards and Edmund Burke -- A revolt against humiliation

Two UCSC faculty members provide a perspective on the generational revolution sweeping the Arab world.