The three young artists and professors had no department, no center, no studios of their own. They drifted from place to place like pollen—and some of their fellow faculty members seemed to be allergic. It might have been the turpentine fumes.

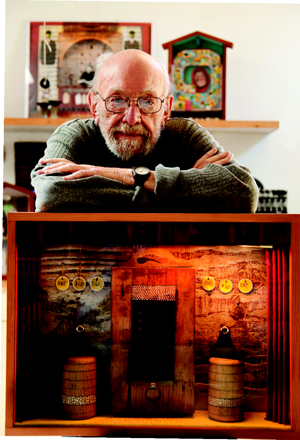

Or it might have been the weird sounds coming from makeshift art classrooms in the campus library and the communications office. “We made odors and noise,’’ said Doug McClellan, 88, professor emeritus of art and an accomplished maker of three-dimensional art boxes. “Remarks were made. We were looked on as interlopers because we had stuff that smelled.”

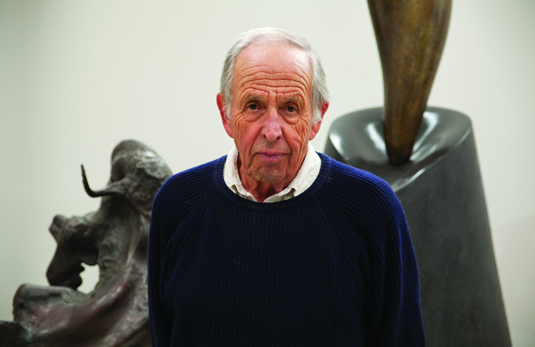

“I had a class—rather messy, I recall—in the basement of one of the buildings,’’ said Jack Zajac, 80, an internationally known sculptor and also emeritus art professor.

In many ways it was a chaotic time for McClellan, Zajac, and the painter Don Weygandt, now 84.

They started teaching at UC Santa Cruz when the campus, founded in 1965, was still brand new. All departments were vying for space. But sometimes, having no options is a form of freedom. They set up in storage rooms, among the cows in a field, and on the first and third floors of Applied Sciences. Weygandt arrived in 1967; Zajac in 1969; and McClellan two years later, after Zajac brought him on board.

If you worked as an art professor at UCSC, it helped if you were an accomplished hiker. Instructors hoofed it several miles a day to get to their makeshift, itinerant classrooms. And somehow, through all that craziness, Weygandt, McClellan, and Zajac put on gallery shows, guided thousands of students, and forged a friendship that lasts to this day.

These and other UCSC art pioneers did more than just influence the direction of UCSC’s art department. They gave students a new way of existing in the world, said Andrea Hesse, a UCSC alumna (Porter ’83, art history) who has worked with Zajac on an exhibition and took classes from both McClellan and Weygandt.

“I learned how to hand-sharpen our pencils, using sand paper to file them to a precise point,” Hesse said. “Having that close a relationship to your materials, to your medium, and to your craft was very important. When I think about art as life, Doug is the person I learned that from.”

Their art classes changed lives.

“Often, students who really lost themselves in the classes would go out into nature and see colors, forms, and relationships that weren’t present before in quite that way,” Weygandt said. “What you are really teaching them is another language that they have already, but one that they had not been allowed to exercise and develop.”

Drawing up a department

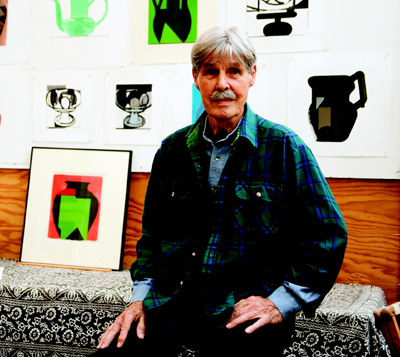

Monoprint maker Don Weygandt

Monoprint maker Don WeygandtAfter arriving on the UCSC campus, the artists were brimming with ideas. Prior to teaching at UCSC, McClellan chaired the art department at Scripps College, one of the Claremont Colleges, and the Claremont Graduate School M.F.A. program.

Weygandt, son of a coal miner, studied art on the GI Bill, as did McClellan. He was lured to UCSC by the sculptor and art professor Gurdon Woods, who was a former director of the San Francisco Art Institute, where Weygandt had taught art alongside such luminaries as abstract painter Richard Diebenkorn, a longtime friend and colleague.

Zajac had been in Italy on a prestigious Prix de Rome art prize. His trips to the countryside outside the city inspired his lifetime fascination with the goats, sheep, and “poetic caprice of water” that figure prominently in his work. One of his works, “Sacrificial Goat”—dedicated to two members of UCSC’s pioneer class who died in the Vietnam War—still stands at Cowell College.

“By the time we all got to UCSC, each of us had accumulated a kind of vocabulary, a teaching syllabus drawn from our personal experience,” Weygandt said.

Those early students were “wonderful,” McClellan said. “They had never really taken art courses. Wow, they were raw, but so smart and motivated.”

With such inspired pupils, who needs a proper classroom? Zajac liked to teach sculpture out on the pond at nearby Westlake Park, using a wax made of paraffin, beeswax, and resin.

“I had a station wagon with a burner in the back,” Zajac said. “We’d melt the wax and go out to look at the grebes and ducks and geese. They would swim and sleep and fly and sometimes attack us. The students would get a handful of wax and look at these creatures and try to replicate these images in forms that could fit in your hand.”

A formal art department did not even exist until several years after they started teaching at UCSC.

Practice and hard work

Art box maker Doug McClellan

Art box maker Doug McClellanThese days, the three men have been retired, and senior citizens, for almost the same nmber of years that they taught at UCSC. The art landscape at UCSC has utterly transformed since the time they taught there.

“I don’t even recognize my way around up there,” said their colleague Hardy Hanson, who, like the others, is long since retired. UCSC now has a lavish arts complex including the Elena Baskin Visual Arts Center—which opened too late for them to make full use of it—and a $35 million Digital Arts Research Center, which opened this year and would have sounded like a science-fiction daydream in the ’60s. But in those scrappy early days of art-making at UCSC, they made do without fancy facilities.

McClellan worked hard to disarm the students, to free them from self-consciously trying to do “good work” by giving them prompts that would surprise them and catch them off guard in a low-pressure way. “The spirit of play has always been important to me.”

Like his cohorts, Zajac emphasized hard work and inspiration. “Some of the students were enthusiastic but somewhat hopeful that art would come without the work it requires,” Zajac said.

The campus continues to build on the tradition established by UCSC’s art pioneers, said Dean of the Arts David Yager. “It’s incredible for me, talking to alumni from the first, second, and third classes and realizing that their experience is very similar to the kind of experience I want our students to have now,” Yager said. “Although some of the tools students use have changed, it’s still about the content and the ideas.”

Still vital after all these years

New Arts Division fund honors pioneer arts faculty

UC Santa Cruz’s pioneer arts faculty helped establish the campus’s visual arts, music, and theater departments.

Now they are about to get the recognition they so richly deserve. Two alumni from pioneer classes—Jock Reynolds, class of 1969, and Peder Jones, class of 1970—have teamed up with several other pioneer-era alumni to form a special endowment fund honoring influential arts faculty from the early years of UCSC.

The Division of the Arts has just announced the formation of the Pioneer Faculty Endowed Fund: A Legacy for the Future of the Arts—which will provide annual awards to students and faculty.

"Those awards will support and sustain direct contact between faculty and student artists," said Lesley Brander, director of development for the Division of the Arts. "Reynolds and Jones felt their education was based on the fact that these teachers took the time to mentor students one-on-one. This endowment will encourage and preserve that spirit of mentorship.

"Their experience with those faculty significantly changed their lives," Brander continued. “This comes out of their love for the education they received."

Individual alumni can donate money to the fund, or groups of alumni can pool their resources to name individual honorees. These funds will be channeled into the Pioneer Arts endowment.

For more information, contact Lesley Brander at lbrander@ucsc.edu.

Zajac, McClellan, and Weygandt are still making art, still in regular contact, and still in Santa Cruz County.

“We respect each other as artists, and we’re not in competition,” McClellan explained. “It’s like the Mafia. We don’t mess with each other’s territory.”

McClellan made—and still makes—art boxes that combine wildly disparate elements: lentil-shaped doll’s eyes, El Greco figures, Hubble space imagery, Day of the Dead skulls, insects, house-hold tools, Eadweard J. Muybridge’s kinetic photos—and makes them work together. In one of his “Wow Boxes,” viewers peer through a spy hole and get pulled into a dreamscape of leaning towers and endless M. C. Escher corridors.

Weygandt continues to make highly regarded monoprints. Like one of his many inspirations, the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, he uses unassuming forms—vases, pots, and pitchers—and finds infinite variations of form, texture, light, and color.

Zajac, like the others, is disarmingly humble, so it takes some digging to find out that he is a Guggenheim Fellowship recipient, and that his work is part of the holdings of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art, among many others. “They keep my work in a place of honor,” he said, in regard to MOMA. “It’s down in the basement.”

Zajac speaks of his UCSC colleagues with the same admiration that he bestows on far more famous artists. At his home, the work of Hardy Hanson and Weygandt hang side by side with the work of Giacometti and Morandi, and he calls McClellan “the Duchamp of our time.”

Clearly the three understand each other’s overlaps and differences.

“Jack is a refiner,” McClellan said. “His work depends on exactness, the finish, the clarity. Don is all about re-working. I’m more of a fumbler.

As different as they are, the three have striking commonalities. McClellan and Weygandt both served in World War II—though not together, and they did not face combat.

McClellan often lunches with Zajac. McClellan and Weygandt have a longstanding bocce rivalry. All have worked a number of odd jobs on their way to becoming artists, though Zajac has the most distinction in that regard, having served as a painter of grocery store window advertisements, a fisherman, a caller at a bingo parlor, and the house fiddler at a coffee shop.

McClellan and Zajac have known each other off and on since they were young men. The three men also share a trait common to artists; when it comes to inspiration and career paths, there is no such thing as a straight line. Their friendships and long careers are the result of false starts, unexpected changes, snap decisions, and coincidences. The only constant in their lives, their teaching, and their adventures is perseverance.

“Life will lead you where it will,” Weygandt said.