At a very early age, children learn how to classify objects according to their shape. Now, new research suggests studying the shape of the aftermath of supernovas may allow astronomers to do the same.

A new study of images from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory on supernova remnants--the debris from exploded stars--shows that the symmetry of the remnants, or lack thereof, reveals how the star exploded. This is an important discovery because it shows that the remnants retain information about how the star exploded, even though hundreds or thousands of years have passed.

"It's almost like the supernova remnants have a 'memory' of the original explosion," said Laura Lopez, a graduate student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who led the study. "This is the first time anyone has systematically compared the shape of these remnants in X-rays in this way."

Astronomers sort supernovas into several categories, or "types," based on properties observed days after the explosion. Those properties reflect the very different physical mechanisms that can cause stars to explode. But since observed remnants of supernovas are leftover from explosions that occurred long ago, other methods are needed to accurately classify the original supernovas.

Lopez and colleagues focused on relatively young supernova remnants that exhibited strong X-ray emission from silicon ejected by the explosion so as to rule out the effects of interstellar matter surrounding the explosion. Their analysis showed that the X-ray images of the ejecta can be used to identify the way the star exploded. The team studied 17 supernova remnants in the Milky Way galaxy and a neighboring galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud.

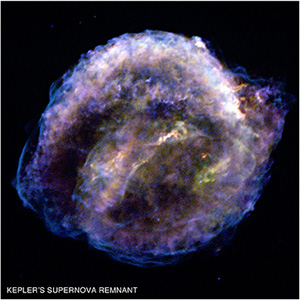

For each of these remnants, there is independent information about the type of supernova involved, based not on the shape of the remnant but, for example, on the elements observed in it. The researchers found that one type of supernova explosion--the so-called Type Ia--left behind relatively symmetric, circular remnants. Type Ia supernovas are thought to be caused by the thermonuclear explosion of a white dwarf and are often used by astronomers as "standard candles" for measuring cosmic distances.

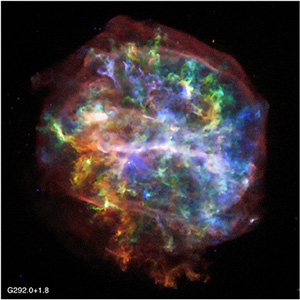

On the other hand, the remnants tied to so-called core-collapse supernova explosions were distinctly more asymmetric. This type of supernova occurs when a massive young star collapses onto itself and then explodes.

"If we can link supernova remnants with the type of explosion, then we can use that information in theoretical models to really help us nail down the details of how the supernovas went off," said coauthor Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

Models of core-collapse supernovas must include a way to reproduce the asymmetries measured in this work and models of Type Ia supernovas must produce the symmetric, circular remnants that have been observed.

Out of the 17 supernova remnants sampled, 10 were classified as the core-collapse variety, while the remaining seven were classified as Type Ia. One of these, a remnant known as SNR 0548-70.4, was a bit of an "oddball." This one was considered a Type Ia based on its chemical abundances, but Lopez said it has the asymmetry of a core-collapse remnant.

"We do have one mysterious object, but we think that is probably a Type Ia with an unusual orientation to our line of sight," said Lopez. "But we'll definitely be looking at that one again."

While the supernova remnants in the Lopez sample were taken from the Milky Way and its close neighbor, it is possible this technique could be extended to remnants at even greater distances. For example, large, bright supernova remnants in the galaxy M33 could be included in future studies to determine the types of supernova that generated them.

The paper describing these results appeared in the November 20 issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters. NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., manages the Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory controls Chandra's science and flight operations from Cambridge, Mass.

More information, including images and other multimedia, can be found at the web site of the Chandra X-ray Observatory Center and NASA's Chandra mission web site.