Where do blood cells come from? How do neurons develop to create the complex wiring of the brain? Can we build a better microscope to study living cells?

These are among the questions UCSC stem cell researchers are investigating with funding from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM). Their work could lead to breakthroughs in the treatment of cancer, heart disease, neurological and muscular disorders, and many other conditions.

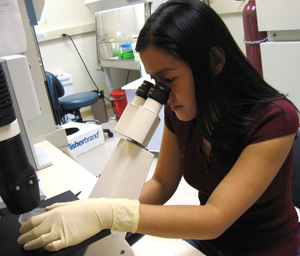

The UCSC Stem Cell Symposium--held on Wednesday, February 25, in the Science & Engineering Library--showcased a variety of stem cell research projects now under way on campus. It was also an opportunity to celebrate the opening last year of UCSC's Shared Stem Cell Facility, a state-of-the-art laboratory built with CIRM funding.

"We are really pleased to be a part of the basic research effort that goes into developing stem cell technology and, ultimately, its medical applications," said David Haussler, director of UCSC's stem cell training program and professor of biomolecular engineering in the Jack Baskin School of Engineering.

Haussler, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, also directs UCSC's interdisciplinary Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering, which manages the campus's CIRM grants. With the addition of a $2.2 million training grant approved earlier this month, CIRM funding awarded to UCSC now totals $19.4 million.

"We believe Santa Cruz is one of the key parts of our whole operation," said CIRM president Alan Trounson, who emphasized the importance of partnerships between stem cell scientists at UCSC and clinical researchers working to develop new stem cell-based therapies to treat conditions such as diabetes, spinal cord injuries, and heart disease.

"There is good reason to make those connections with clinicians, because your basic science is critical to where they're going," he said.

One way in which stem cells may be used to treat diseases is through cell transplants to replace tissue that is damaged by disease or injury. Embryonic stem cells have the potential to develop into any type of cell in the body. But researchers must learn how to guide the development of stem cells in the lab to produce just the cell type needed for a particular therapy.

"Stem cells may provide an unlimited resource for therapy if we can learn to guide the differentiation of cultured stem cells in the petri dish," said Bin Chen, assistant professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology.

Chen described work in her lab to reveal the molecular mechanisms that control the development of neural stem cells into different types of neurons in the brain. Understanding these mechanisms is a key step in learning how to grow specific types of neurons in the lab for use in cell therapy, she said.

Stem cell research also holds promise for developing new cancer therapies. Camilla Forsberg, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering in the Baskin School of Engineering, described her research on the complex pathways by which the many different types of blood cells are produced from blood stem cells in the bone marrow. Errors in the regulation of these pathways lead to diseases such as acute myeloid leukemia, caused by over-proliferation of certain blood cells. Forsberg's lab is studying one of the most frequently mutated genes in acute myeloid leukemia.

"If we could identify the cancer stem cell, then we could use very targeted treatments instead of bombarding it with nonspecific drugs that also affect healthy cells," she said.

Forsberg said her research has benefited greatly from collaborations with computational biologists led by Joshua Stuart, assistant professor of biomolecular engineering in the Baskin School.

Haussler also emphasized the value of computational tools developed at UCSC, including the UCSC Genome Browser, for addressing the challenges of stem cell research. "There are opportunities here for us to provide the genomic database for clinical trials coming out of CIRM research," he said.

Another presentation that highlighted the interdisciplinary nature of UCSC stem cell research described efforts to build a better microscope for stem cell biologists, using technology astronomers have developed to sharpen the images from telescopes.

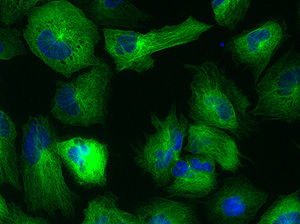

"Imaging is incredibly important for stem cell research," said William Sullivan, professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology. "The problem is that we don't have single-cell resolution for deep tissue imaging."

Adaptive optics technology is used in astronomy to correct for the blurring effect of the Earth's atmosphere, which distorts the images from ground-based telescopes. Sullivan is working with Joel Kubby, associate professor of electrical engineering in the Baskin School, and astronomy researchers at UCSC's Center for Adaptive Optics to develop an adaptive optics microscope for imaging deep within tissues containing stem cells.

The symposium also featured lab tours and poster presentations of research by graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, many of whom are in the stem cell training program. The UCSC Training Program in Systems Biology of Stem Cells provides students and postdoctoral researchers with a solid understanding of the biology of stem cells, the skills to use stem cells in their own research, and the ability to devise and use computational approaches in their stem cell research.

The symposium was sponsored by the UCSC Institute for the Biology of Stem Cells, the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering, the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences, the Baskin School of Engineering, and the Division of Physical and Biological Sciences.