Thanks to the sharp eyes of a UC Santa Cruz undergraduate, astronomers have obtained a surprise view of a never-before-observed event in the birth of a galaxy.

A team of astronomers from UCSC and the University of Florida discovered the onset of a huge flow of gas from a quasar, the super-bright core of an extremely remote young galaxy. The gas was expelled from the quasar and its enormous black hole sometime in the space of four years around 10 billion years ago--an extremely brief and ancient blip detectable only through the unlikely convergence of two separate observational efforts.

"It was completely serendipitous," said Fred Hamann, a UF astronomy professor. "In fact, the only way it could have happened is through serendipity."

The discovery was initiated when UCSC undergraduate Kyle Kaplan earlier this spring noticed peculiarities in the spectra, or wavelengths of light, that had been observed and recorded from the quasar. Kaplan was working with Jason X. Prochaska, associate professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCSC, who had gathered the spectra in 2006 (together with former UCSC undergraduate Stephane Herbert-Fort) as part of an effort to study the galaxies between the quasar and Earth. Prochaska was aware of Hamann's work on quasars and asked him to take a closer look.

"It is much to Kyle's credit that he chose not to ignore these changes in the quasar, which were unrelated to his research," Prochaska said. "As with many great discoveries in astronomy, one must always be open to the unexpected."

A paper about the research appeared online this month in the Letters of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

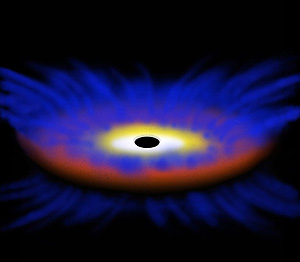

Quasars are enormously bright cores of very distant galaxies thought to contain supermassive black holes a billion times larger than our sun. They are seen only in the centers of very distant galaxies that formed long ago--galaxies whose light is just now reaching Earth after billions of years in transit. The quasar in question is about 10.3 billion light years from Earth.

The black holes within quasars are invisible, but the cosmic material cascading toward them builds up and forms hot "accretion" disks, the source of quasars' intense light. Some of the incoming material also can be expelled from quasars to form enormous gas clouds that zoom out at extremely high speeds. With the quasar in question, the gas is flowing at an astonishing rate of 58 million mph, Hamann said.

But while astronomers had observed the presence of such gas clouds with other quasars, they had never witnessed one actually coming into being--until now.

Following up on Kaplan's observations, Hamann and other astronomers checked the 2006 spectra against the spectra of the same region recorded in a separate sky survey in 2002. To their surprise, they found no evidence of the gas cloud in 2002.

"So that's how we know this appeared between 2002 and 2006," Hamann said.

The discovery opens a window to understanding more about how quasars come into being and their role in the evolution of galaxies.

"The fact that we saw one appear in so short a time frame means that it's a volatile type of structure," Hamann said. "It could be an evolutionary phase, or maybe a transition stage from one phase to another."

Astronomers hope future observations will prove telling.

"One interesting question in astronomy is how does the evolution of quasars relate to the evolution of galaxies?" Hamann said. "The matter ejected from quasars might be the key to this relationship because it can disrupt or regulate the formation of galaxies around quasars. This discovery is a small piece of that story that we can see happening in real time, and what we are going to do now is keep watching."

Other coauthors of the paper are Paola Rodriquez Hidalgo, a UF graduate student, and Stephane Herbert-Fort, now a graduate student at University of Arizona and a UCSC alumnus.