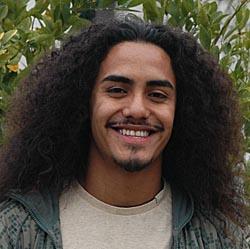

A native of East Los Angeles, Angel Martinez was 12 years old when his baby sister was born four months premature. So tiny she would've fit in the palm of his hand, baby Dilia was kept in isolation and wouldn't know her brother's touch for two months.

Today, Dilia is a happy 9-year-old, with few traces of those trying months, and Martinez credits her with shaping his own life. "Seeing the struggle my sister went through just to be alive was not just inspiring, but a driving force today," he said. "That's when I decided I wanted to be a doctor. I wanted to know what was going on with her."

A senior at UCSC, Martinez is majoring in health sciences and Barbara Jordan Health Policy Scholars Program in Washington, D.C. One of only 15 scholars chosen from 350 applicants, Martinez spent 10 weeks this spring and summer learning about health policy, particularly issues that affect minorities and underserved communities. The program is supported by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

"It's one of the most amazing, life-changing opportunities I've ever had," said Martinez, who worked side-by-side with legislative assistants in the office of Congresswoman Hilda Solis (D-El Monte). He wrote memos, drafted a speech for Solis, attended a historic Congressional hearing on health disparities convened by Solis, and got an incredible overview of the legislative system.

"What I really understand now is that policy is the background work to how our entire health care system works," said Martinez. "I had the privilege of gaining a broader perspective."

As part of the fellowship, Martinez drafted a policy memo on living with HIV/AIDS that focused on improving services for people in the Los Angeles area. "You don't just talk about one thing. You have to think about costs, effectiveness, the needs of underserved and vulnerable populations," he said. "You don't just think in one dimension."

The truth is that racial and ethnic health disparities aren't a priority for a lot of legislators, he said. "But one of the impacts of this program is that we bring these perspectives from our communities to Congressional staffers and legislators who may not yet be playing a role in these areas," said Martinez, who recalled stepping inside the Capitol for the first time and asking himself, "How did I end up here?"

He will remain in the nation's capital through December as an intern with Mary's Center for Maternal & Child Care as he completes the field-study requirement of his community studies program.

Martinez grew up playing soccer, baseball, and basketball, but school wasn't a priority. "I barely got through second through sixth grade," he recalled. His parents, who had immigrated to the United States from Mexico as children, had never attended college, and they wanted more for their children. They chose an unusual avenue for Martinez: They sent him to the city pool to play water polo.

"It went from a hobby to being my life--I stopped going out with friends because I was always at the pool. It's where I learned discipline, teamwork, and working with other people," he said. "It pulled me away from the street environment I could've fallen into. I found another way to release my energy."

Martinez liked the intensity of water polo, which challenged his physical capabilities, and it also opened new doors. He enrolled at Cathedral High School in downtown Los Angeles, one of the few schools that offered the sport, and he joined an elite club team, the City of Commerce Aquatics, that competed nationally.

Competing on all-Latino teams in the white-dominated sport also exposed Martinez to racism for the first time. "It ticked people off to lose to a team like ours," he said.

At UCSC, Martinez was the only nonwhite player on the water polo team, but playing college water polo was a dream, he said. The Slugs won the Division Three national championship during his third year, and last fall, he wrapped up his fourth and final year with the team.

"I had the largest culture shock when I came to this city," recalled Martinez, who said the campus looked to him like a farm. He missed his family, his neighborhood, and he missed speaking Spanish.

Martinez enrolled in pre-med classes but found his footing through friends and by taking classes in Latin American and Latino studies, getting involved with Chicano Teatro, Chicanos/Latinos for Health Education (CHE), and MEChA, the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Atzlan, the Chicano student organization.

A double major in health sciences and community studies rounded out his academic program, and faculty mentors reinforced his commitment to serving others. "The thing that drives me the most is my family," he said. "I'm not just doing this for myself. I'm doing it for people back home. If I can do it, anybody else can, too."