SANTA CRUZ, CA--From African American residents of West Oakland's diesel-choked neighborhoods to Latinos in San Francisco's traffic-snarled Mission District, poor and minority residents of the San Francisco Bay Area get more than their share of exposure to air pollution and environmental hazards.

That's the conclusion of a new report issued by the Center for Justice, Tolerance, and Community (CJTC) at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The first published analysis of the overall state of environmental disparity in the nine-county region, the report is entitled, "Still Toxic After All These Years... Air Quality and Environmental Justice in the Bay Area."

"Despite more than 20 years of activism and research, environmental inequality is unfortunately alive and well in the Bay Area," said study coauthor Manuel Pastor, director of CJTC and a professor of Latin American and Latino studies at UCSC.

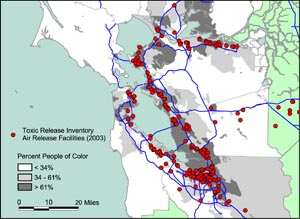

The study documented environmental disparity by analyzing several different databases on toxic air emissions and concentrations from stationary facilities, such as factories and refineries, as well as mobile sources, like traffic. These data were combined with neighborhood demographics from the 2000 Census, including income levels, ethnicity, and language fluency. It covered the counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, and Sonoma.

Among the key findings:

. Two-thirds of residents who live within one mile of an EPA Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) facility are people of color, while nearly two-thirds of people who live more than 2.5 miles are white.

. Recent immigrants are nearly twice as likely to live within one mile of a TRI facility as they are to live 2.5 miles away from one.

. Although the likelihood of living near a TRI facility declines as income rises, racial disparity exists at every level of income.

"The patterns are clear and indisputable," said Pastor. "Even after controlling for income, land use, and other variables that are frequently used to explain away disparate patterns of exposure, communities of color face greater exposure to air pollution and toxics. They bear a disproportionate burden and face greater hazards and risks than others in the Bay Area."

Pastor called for a comprehensive approach that focuses on reducing persistent inequalities and preventing exposures and health risks before they occur. "Surely, the Bay Area can develop an environmental justice policy that leads the state," he said. "As we witnessed in the Katrina disaster, leaving some of us less protected ultimately poses environmental risks for everyone."

The report also presents estimates of cumulative lifetime cancer and respiratory risks associated with ambient air toxics exposure. Based on assumptions about ambient exposures and toxicity, rather than actual cancer or respiratory cases, the estimates are useful for comparing the overall pollution burdens between neighborhoods and clarifying what the implications may be for health, said Pastor.

Areas at higher risk for cancer and respiratory hazards have higher proportions of minority and immigrant residents, as well as higher percentages of land devoted to industrial, commercial, and transportation uses, the authors found.

"In the Bay Area, more than 70 percent of estimated cancer risk from ambient air toxics comes from traffic," he said. Many neighborhoods are already well over the regulatory goal of 10 cancers in a million that is used in regulating new facilities, pointing out the need for a cumulative approach to exposure management. "A little risk here, a little risk there, and soon you have health risks that are orders of magnitude above the benchmarks considered to be of regulatory concern," said Pastor.

Among the policy guidelines discussed in the report:

. Consider cumulative impacts because air pollution and environmental hazards may accumulate and interact to impact community health in ways that are poorly understood.

. Consider social vulnerability because evidence suggests that environmental hazards have gravitated over time to places with the least economic, social, and political power.

. Promote meaningful community participation to generate trust and help regulators, activists, and policy makers establish common ground.

. Take meaningful action to protect the public health.

The authors also called on the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD) to increase access to critical data sets and emissions inventories and to collaborate more with cities, counties, and public stakeholders to expand its inventories to include unregulated sources.

Finally, as environmental cleanup expands and property values increase, Pastor issued a plea on behalf of current residents and activists, who could be displaced by the tides of gentrification. "Those who have suffered through the toxic soup for years should be among those to reap the rewards from a new commitment to environmental justice," said Pastor.

In addition to Pastor, the report was coauthored by James Sadd, associate professor of environmental science at Occidental College, and Rachel Morello-Frosch, an assistant professor at the Center for Environmental Studies and the Department of Community Health at Brown University. The study was a partnership of CJTC and the Bay Area Environmental Health Collaborative (BAEHC), with support from the California Endowment, the California Wellness Foundation, the San Francisco Foundation, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation.

#####

Note to journalists: Manuel Pastor can be reached at (831) 459-5919 or via e-mail at mpastor@ucsc.edu. The report "Still Toxic After All These Years... Air Quality and Environmental Justice in the Bay Area" will be posted on the CJTC web site, cjtc.ucsc.edu on Saturday, February 17.